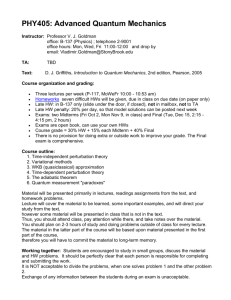

Fall 2013 Reader

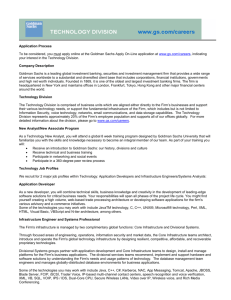

advertisement