CLIL - Universitat de Barcelona

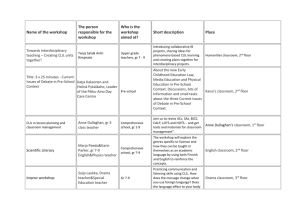

advertisement

CLIL-SLA Project: Antecedents. Results on the Effects of CLIL on EFL Learning To the memory of Mia Victori (1966-2010) sites.google.com/site/clilslaproject/apac-2011 Antecedents Studies from • UB: GRAL Project (UB) (Co-ord: Muñoz) – Marc Miret MA thesis (Navés) – Navés & Victori (2009) & Navés (2011) • UAB: – Vallbona MA thesis 2009 (Victori) – Bret MA thesis in progress (Victori & Pladevall) Beliefs vs. Mainstream Research 1. The age factor: The sooner the better (García-Mayo & García Lecumberri, 2003; Muñoz, 2006, 2008, 2009, 2010; Navés 2006; Celaya & Navés, 2008)) 2. Study abroad (SA). 3. CLIL maybe but the evidence comes from – Short-term studies vs Long-term studies. Statistically significant differences vs. Relevant educational gains. (Navés, 2010) Quantitative vs Qualitative studies (Escobar, 2009; Wittaker, 2010) Cross-sectional studies vs. Longitudinal studies (See SLA-CLIL project in Pladevall et al., forthcoming) Linguistic-oriented studies vs Content-oriented and CLIL-oriented studies Product-oriented vs Process Oriented studies Comparison of existing curricula vs. finely-grained studies: The control of the variables: amount of instruction, type of school, etc. (García-Mayo, 2010; Muñoz and Navés, 2007; Navés & Victori, 2009) – – – – – (Pérez-Vidal, 2001, 2009. But Llanes & Muñoz, 2009) CLIL • The subject matter or part of the subject matter is taught via a foreign language with a two-fold objective: the learning of those contents and the simultaneous learning of a foreign language (Marsh, 1999:27) The best way to learn an L2: Teaching subject matter in the L2 • Using the L2 to teach subject matter is more effective than teaching the language directly, treating the L2 itself as the subject matter (Krashen, 1982). • Teaching subject matter in a second language is the best possible way to encourage second language acquisition. (Spada and Lightbown, 2002) CLIL The European Commission’s (2005) report on foreign language teaching and learning claims that an excellent way of making progress in a foreign language is “to use it for a purpose, so that the language becomes a tool rather than an end in itself.” (p.9) European Council (1995): A1-A2 - B1-B2 - C1-C2 1)Lowering the starting age and simultaneously 2) CLIL instruction CLAIMS: CLIL > EFL • CLIL instruction is more successful than traditional form-focused EFL learning (Piske, 2008, Do Coyle, 2009). • CLIL methodology provides plenty of real and meaningful input to learners and raises their overall proficiency in the target language. (Coyle, 2002 p.258). But… • Not all content-based instruction results in good language learning (Swain, 1988) • CLIL provides some of the necessary conditions for good effective language learning to take place but is not a guarantee of success (de Graaf et al. 2007; Muñoz, 2007; Navés in press) Short-term statistical significant differences versus long-term relevant education gains. Lindholm-Leary (2007) Empirical Research CLIL>EFL • Writing Performance: – – – – – – Ackerl (2006) - Carrilero(2009); Miret (2009) Huttner et al (2006) - Lasagabaster (2008) Loranc-Paszylk(2009) - Navés and Victori (2010) Navés (2010) - Miret (2009) Miret & Navés (in preparation) Vallbona & Victori (in preparation) • English Proficiency : – – – – – – – Admiraal et al.(2006) - Jiménez et al.(2006) Kasper (1997) - Lasagabaster (2008) Navés and Victori (2010) - Vallbona (2009) Pérez-Vidal (2010) - Lorenzo et al. (2009, 2010) Ruiz de Zarobe & Jiménez Catalán (2009) Villarreal Olaizola & García Mayo (2009) García Mayo & Villarreal Olaizola (2011) Reasons for the present studies • An increasing number of schools in Catalonia are teaching subjects or parts of subjects in English (CLIL) to improve students’ language competence. • Despite this, academic research on CLIL programs is still embryonic in Catalonia (Navés and Victori, 2010). • We need local studies comparing CLIL with traditional instruction to support the presumed benefits of this approach and to find out the weaknesses and strengths of CLIL. • We need to evaluate language development in CLIL instruction as well as classroom dynamics and how this affects the outcomes of the approach. How did we collect data? TESTS • QUANTITATIVE INSTRUMENTS • Language Proficiency Tests:* – – – – Listening Comprehension Test Dictation Test Cloze Test Grammar Multiple-choice • Written Composition • Oral Tests (Interview & Narrative) *Developed, validated and used by the BAF Project (Muñoz, 2006) • QUALITATIVE INSTRUMENTS • Students’ Background Questionnaire • Interview with the CLIL Teachers • CLIL Class Observations • CLIL Students’ Opinion Questionnaire CAF measures COMPLEXITY Accuracy Fluency Miret’s Participants Miret’s Results Naves & Victori (2009) & Navés (2011) Participants Grammar Test Dictation Cloze: Reading Comprehension Writing Fluency (Essay length) Writing Syntactic Complexity (clauses per sentence) Writing Lexical Variety (Giraud’s index) Summary of Results Miret (2009), Navés & Victori (2010) and Navés (2011) • Overall 5th and 7th grade CLIL learners better than their non-CLIL peers from 5th and 7th and did as well as learners two grades ahead – in all the proficiency tests except in the listening test – and in all the writing domains examined except in accuracy. RESEARCH STUDIES • Vallbona MA thesis 2009 (Victori) • Victori & Vallbona (2010) • Bret MA thesis in progress (Victori & Pladevall) PARTICIPANTS & DATA COLLECTION GROUPS GRADE LEVEL DATA COLLECTION TIME EXPOSURE TO ENGLISH 5th Primary N = 25 5th Primary N=8 October 2006 3hr/week EFL 6th Primary N= 27 6th Primary N= 8 October 2006 3hr /week EFL 5th Primary N =22 5th Primary N=8 October 2009 6th Primary N = 24 6th Primary N=8 October 2009 NON-CLIL GROUPS CLIL GROUPS 3hr/ week EFL + 1hr/week Science in English (105 hours ) 3hr/ week EFL + 1hr/week Science in English (105 hours) RESULTS LANGUAGE PROFICIENCY AND WRITING TESTS 5th GRADERS CLOZE TEST LISTENING DICTATION NUMBER OF WORDS IN ENGLISH ORAL TESTS: 5th GRADERS ACCURACY FLUENCY Interview LEXICAL COMPLEXITY ORAL TESTS: 5th GRADERS ACCURACY Narrative SYNTACTIC COMPLEXITY LEXICAL COMPLEXITY LANGUAGE PROFICIENCY AND WRITING TESTS 6th GRADERS CLOZE TEST NUMBER OF ERROR FREE CLAUSES LISTENING DICTATION NUMBER OF WORDS IN ENGLISH NUMBER OF CLAUSES ORAL TESTS: th 6 Interview FLUENCY GRADERS ORAL TESTS: 6th GRADERS ACCURACY Narrative FLUENCY LEXICAL COMPLEXITY SYNTACTIC COMPLEXITY ORAL DATA: QUALITATIVE ANALYSIS • Number of one-word utterances • Amount of subordination • Type of coordination RESULTS Proficiency & Writing Tests - Improvement of receptive skills, such as listening, reading and dictation (Admiral et al, 2006; Gassner & Maillat, 2006; Mewald, 2007; Lasagabaster 2008; Ruiz de Zarobe, 2008;Vallbona, 2008; Loranc-Paszylk, 2009; Miret, 2009; Naves & Victori, 2010). - Writing areas: fluency, accuracy, lexical complexity do not necessarily develop simultaneously as students become better writers (Naves et al, 2003; Foster & Skeken, 1996). Oral Tests - CLIL learners outperformed non-CLIL learners in many of the aspects analysed (Admiraal et al, 2006; Hüttner & Rieder-Büneman, 2007; Mewald, 2007; Jiménez et al, 2007; Ruíz de Zarobe, 2007; Lasagabaster, 2008; Juan-Garau 2010; Várkuti, 2010). - Improvement of fluency and syntactic complexity. What did children think of Science? CLIL students’ opinion questionnaire results Overall assessment of the CLIL experience: very positive. •Did you like doing Science in English? YES! 5th graders 70% CLIL students’ opinion questionnaire results The teacher gave good explanations The activities were fun WHY? We are interested in English Science is our favourite subject CLIL students’ opinion questionnaire results YES! 5th graders 56% Did you find Science easy? CLIL students’ opinion questionnaire results Familiar topics The activities were easy easy? We have an ability for languages Science is our favourite subject CLIL students’ opinion questionnaire results Understanding some concepts Answering in English What was difficult ? Understanding some of the teacher’s explanations Understanding some words Limitations These promising results have, nevertheless, to be analysed with caution because the amount of hours of instruction was not kept constant of the different types of schools involved cross-sectional, product-oriented nature. short-term nature. Limitations and Conclusions • Limitations of these types of studies (See Muñoz & Navés, 2007) • Statistical significant differences vs. Relevant gains from an education and language policy perspective. Final remarks 1) Unlike the results found when examining (a) an early start, (b) stay-abroad (c) out-of-school instruction, the preliminary results from short-term crosssectional research on CLIL instruction --in spite of its limitations and confounds-- seem promising. Final remarks 2) Although the preliminary short-term of CLIL instruction results are encouraging, we still need to see whether (a) carefully planned studies confirm the benefits already found and furthermore whether (b) in the long run CLIL instruction will not just show a statistically significant difference but would make it possible to drastically raise the levels of proficiency of European learners as called for by the Council of Europe (1995). Further evidence is needed 1. Short-term studies vs Long-term studies. Statistically significant differences vs. Relevant educational gains. (Navés, 2010) 2. Quantitative vs Qualitative studies and Product vs Process oriented studies. Mixed-methodology studies (Escobar, 2009; Wittaker, 2010) 3. Cross-sectional studies vs. Longitudinal studies (See SLA-CLIL project in Pladevall et al., forthcoming) 4. Linguistic-oriented studies vs Content-oriented and CLIL-oriented studies 5. Comparison of existing curricula vs. finely-grained studies: The control of the variables: amount of instruction, type of school, etc. (García-Mayo, 2010; Muñoz and Navés, 2007; Navés, 2010) (See SLA-CLIL project in Pladevall et al., forthcoming) Thank you very much Moltíssimes gràcies Muchas gracias Eskarrik-asko Graciñas CLIL-SLA Project: Antecedents Teresa Navés tnaves@ub.edu Marc Miret marc.miret@uab.cat Anna Vallbona anna.vallbona@uvic.cat Anna Bret annabret@escolapaidos.cat GRAL Project (UB) & CLIL-SLA Project (UAB) www.ub.edu/GRAL/Naves CLILSLAProject@gmail.com CLIL-SLA Project To the memory of Mia Victori Anna Bret Amanda Cooper Carme Florit Natalia Maldonado Patricia Martínez Marc Miret Teresa Navés Elisabet Pladevall (Co-ord) Anna Vallbona Alex Vraciu Characteristics of Successful CLIL Programmes (Navés, 2009, 2002) (1) Respect and support for the learner’s L1 language and culture (2) Extremely competent bilingual teachers i.e. teachers fully proficient in the language of instruction and familiar with one of the learners’ home languages (3) Mainstream (not pull-out) optional courses (4) Long-term, stable programmes (5) Parents’ support for the programme; Characteristics of Successful CLIL Programmes (Naves, 2009, 2002) 6. Joint effort of all parties. Cooperation and leadership of educational authorities, administrators and teachers 7. Dually qualified teachers (in content and language) 8. High expectations and standards 9. Availability of quality CLIL teaching materials 10. Properly implemented CLIL methodology Muchas gracias Thank you very much Moltíssimes gràcies Eskarrik-asko Graciñas Teresa Navés tnaves@ub.edu (GRAL project & CLIL-SLA project) www.ub.edu/GRAL/Naves CLILSLAProject@gmail.com MUCHAS GRACIAS / THANK YOU / MOLTES GRÀCIES www.ub.edu/GRAL/Naves/ CLILBarcelona@gmail.com CLILSLAProject@gmail.com • M. Jesús Frigols and Gisela Conde for having invited me to this round table. •The Catalan Department of Education (Dolors Solé) for the pilot Barcelona content-based programme I co-ordinated with Margarita Ravera and Cristina Riera for four years (1994-1998) and their collaboration (Natalia Maldonado) with the CLIL-SLA Project funded by the Ministry of Education (2011-2013) • David Marsh, Gisella Langé, Carmen Muñoz Patricia Bertaux and Maria Pavesi for a very productive three-year TIE-European CLIL project (2000-2002). • Ofelia García and James Purpura from Columbia University for having invited me to observe inspiring Bilingual Education classes in NYC in fall 2007 and who are our expert adivsors in the CLILSLA research project (2011-2013) • Yolanda Ruiz de Zarobe, Rosa Mª Catalán, David Lasagabaster, Juan Manuel Sierra, Francisco Gallardo and Jasone Cenoz for having invited me to published in their edited volumes on CLIL. •CLIL-BCN group with Eliseo Picó, Katy Pallás, Carol Mussons, Carmen Velasco, Celia Encabo Juan Cazorla, Lidia Barreiro, and David Hall. • The Spanish Ministry of Education for having funded the research the GRAL project coord. by Carmen Muñoz (UB) and CLIL-SLA Project co-ord. by Mia Victori (UAB) •CLIL-SLA Project (2011-2013): M. Victori, Elisabet Pladevall, Anna Vallbona, Anna Bret, Eleonora Alexandra Vraciu, Patricia Martínez; Marc Miret, Amanda Cooper and Came Florit. Need to justify CLIL? Beliefs and prejudices The defensive attitude that can be inferred from researchers’ need to justify, time and time again, the rationale and benefits of integrating language and subject content rather than further investigating the commonalities of efficient CLIL programmes may have to do with pressure from (a) folk beliefs and prejudices against bilingualism and multilingualism and (b) political interests. (Navés, 2010) CLIL • This approach involves learning subjects such as history, geography and others, through an additional language. (Marsh, 2000) • Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) is a general expression used to refer to any teaching of non-language subject through the medium of a second or foreign language (L2). (Pavesi, 2001) AICLE Aprendizaje Integrado de Contenidos Curriculares y Lenguas Extranjeras implica estudiar asignaturas como historia o ciencias naturales en una lengua distinta de la propia. AICLE resulta muy beneficioso tanto para el aprendizaje de otras lenguas (francés, inglés, ...) como para las asignaturas impartidas en dichas lenguas. (Navés & Muñoz, 2000) SLA foundations of CLIL 1. The transferabilty of skills (Cummins, 1991) 2. BISC vs CALP (Cummins, 1979, 2000; Collier, 1987; 1989) 3. The exposure factor. To increase SL and FL contact hours (Muñoz, 2007; Cenoz, 2003; De Keyser, 2001) 4. The quality of the input. Meaningful learning (Krashen, 1997) 5. Focus on Form (Long 1997; Doughty, 2001; Ellis, 2005) SLA foundations of CLIL • • • CLIL promotes negotiation of meaning, through interaction (Lightbown and Spada, 1993; Long, 1983). Comprehensible input (Krashen, 1985), is a necessary but not a suffcient condition. Cognitively demanding but context-embbeded (Cummins, 1991) Learners also need an focus on relevant and contextually appropriate language forms to support content learning (Lyster, 1987; Met, 1991) SLA foundations of CLIL 1. Creates conditions for naturalistic language learning 2. Provides a purpose for language use in the classroom 3. Has a positive effect on language learning by putting the emphasis on meaning rather than form and 4. Drastically increases the amount of exposure to the target language (Dalton-Puffer, 2007; Dalton-Puffer & Smit, 2007; De Graaf et al. 2007; Muñoz, 2007; Muñoz & Navés, 2007; Navés and Victori, 2010, Navés, in press). CLIL benefits for Content from Llinares (2009) • Learners are more successful and more motivated than those in traditional content subject classrooms (Wolff, 2004) • Learners look at content from a different and broader perspective when it is taught in another language (Multi-perspectivity) (Wolff, 2004) • Learners develop more accurate academic concepts when another language is involved (Lamsfuss-Schenk, 2002) • In CLIL content subject related intercultural learning takes place (Christ, 2000) Characteristics of Successful CLIL Programmes (Navés, 2002, 2009) (1) Respect and support for the learner’s L1 language and culture (2) Extremely competent bilingual teachers (3) Mainstream (not pull-out) optional courses (4) Long-term, stable programmes (5) Parents’ support for the programme Characteristics of Successful CLIL Programmes (Naves, 2002, 2009) 6. Joint effort of all parties. Cooperation and leadership of educational authorities, administrators and teachers 7. Dually qualified teachers (in content and language) 8. High expectations and standards 9. Availability of quality CLIL teaching materials 10. Properly implemented CLIL methodology. The most successful language learning programmes: Canadian Immersion Canadian Immersion Programmes are by far the most highly acclaimed language learning programmes. SLA researchers, teachers and parents fully agree that the immersion programmes in Canada have been extremely efficient and successful. (Swain, 2000; Swain & Lapkin, 1982). (See Navés, 2009, 2010) Limitations to L2 learning in immersion: more focus on form/s needed • However, the question of whether immersion, especially ‘early’ immersion, is the best model for students in all sociocultural and educational settings has not been satisfactorily answered. Some researchers have found that there are limitations to L2 learning through subject matter teaching alone and have suggested that more direct L2 instruction needs to complement the subject matter teaching (Harley, 1989; Lyster, 1994; Swain, 1988). Source: Spada and Lightbown (2002) Limitations (2) complex subject matter • In addition, some educators and researchers have expressed concern about how well students can cope with complex subject matter taught in a language they do not yet know well (Cummins & Swain, 1986). Source: Spada and Lightbown (2002) Previous Research on CLIL & Writing • Muñoz and Navés (2007) Overview of empirical studies show a 2 year advantage for CLIL learners. • Dalton-Puffer (2007) predicted CLIL would not have significant effects over productive skills • Navés and Victori (2010) CLIL provided an advantage between one and two grades in overall proficiency and writing performance. Jacobs et al (1981) scale RQ1- Writing performance *p is significant at <.05 **p is significant at <.01 RQ 1- Overall Proficiency *p is significant at <.05 **p is significant at <.01 RQ2- Writing performance *p is significant at <.05 **p is significant at <.01 RQ2- Overall Proficiency *p is significant at <.05 **p is significant at <.01 Interview: One-word Answers I Percentages of the mean use of one-word answers in the interview task. 5th year students 6th year students 57,18% 37,29% 38,54% 18,87% Non-CLIL students CLIL students Interview: One-words answers II (1) Non-CLIL INV: SUB: INV: SUB: How old are you? hmmp eleven. At five what will you do? House. (2) Non-CLIL INV: SUB: INV: SUB: What do you like to do in your free time? Football. At half past five what will you do today? Football. (3) CLIL INV: SUB: INV: SUB: How old are you? I’m eleven years old. What did you do last weekend on Saturday and Sunday? I go to the hmmp [//] I go to the Sabadell. (4) CLIL INV: SUB: INV: SUB: what will you do when you finish school? today [/] today …nothing I’m go to home. what did you do last weekend? hmmp I play volleyball and then I go to eat with family Subordination • Instances of subordination produced by CLIL learners: (1) There is a table [for I study]. (2) I go [to eat with my family]. (3) The children is surprise [for the dog is eat for the food in the basket]. (4) [When the children go to the country and to the mountain] see the dog. Coordination Non-CLIL students (5) [Painting] and [plays the guitar]. (6) [Watching tv] [play the computers]. (7) [Play playstation], [play football], [play] CLIL students (8) [Played the football] and [Sunday visit my grandfathers]. (9) I [like read], [play volleyball] and [play with my dog]. (10) [Playing football in my house] and [speak with my trainer of judo].