Section 13.3 Building Effective Teams

advertisement

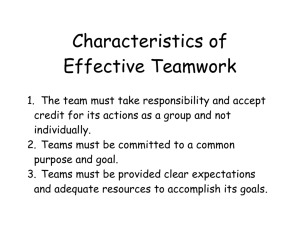

Honors Business Management Chapter 13 – Groups and Teams Key Questions Section 13.1: How is one collection of workers different from any other? Section 13.2: How does a group evolve into a team? Section 13.3: How can I as a manager build an effective team? Getting’ good players is easy. Gettin’ ‘em to play together is the hard part. Section 13.4: Since conflict is a part of life, what should a manager know about it in order to deal successfully with it? Casey Stengel Vocabulary Group Adjourning Team Division of labor Formal group Social loafing Informal group Role Advice teams Task role Production teams Maintenance role Project teams Norms Action teams Cohesiveness Quality circles Groupthink Self-managed teams Conflict Forming Negative conflict Storming Constructive conflict Norming Programmed conflict Group cohesiveness Devil’s advocacy Performing Dialectic method Independent Section Manager’s Toolbox – p. 405 Section 13.2 – pp. 411-412 (see notes page) 1 Section 13.1 Groups & Teams 1. Why is teamwork important? a. + d. + b. + e. - c. + f. - 2. Groups v. Teams GROUPS TEAMS 3. Types of Groups a. Formal b. Informal 4. Purposes of Groups Group Purpose Examples Advice Production Project Action 5. Quality Circles: 6. Self-Managed Teams Section 13.1 Homework: Complete the assignment for the article, Elite Teams Get the Job Done on packet pages.7-14. 2 Section 13.2 Stages of Group & Team Development Stage What Happens What Should You Do? Forming Storming Norming Performing Adjourning 3 Section 13.3 Building Effective Teams 1. Performance Goals and Feedback 2. Motivation thru Mutual Accountability requires a. b. c. d. 3. Size Size Small Large 4. Roles: a. Task b. Maintenance 5. Norms: a. b. c. d. 6. Cohesiveness: a. b. c. d. e. f. g. h. 4 Advantages Disadvantages 7. Groupthink: a. Symptoms of Groupthink i. ii. iii. iv. b. Results of Groupthink i. ii. c. Overcoming Groupthink i. ii. Section 13.3 Homework: Complete the worksheet Can You Manage This? on packet page 14. 5 Section 13.4 Managing Conflict 1. Conflict is the process in which one party ________________________ that its interests are being _______________________ or ________________________ affected by another party. a. Negative Conflict: b. Constructive Conflict: 2. Seven Causes of Conflict a. b. c. d. e. f. g. 3. Five Conflict-Handling Styles a. b. c. d. e. 4. Stimulating Constructive Conflict a. b. c. d. i. Devil’s Advocacy ii. Dialectic Method Section 13.4 Homework: Complete the worksheet Cohension or Dysfuntion on packet page 15. 6 Directions: 1. Read Section One of the Article and answer these questions: a. According to the article, what causes most teams to fail? b. Bonus: To what does the shaded sentence refer? c. What common elements of successful teams did the author identify? d. What lessons did the author learn from each group? (You should have six lessons.) Which lesson was identified as most crucial? 2. Select one of the remaining sections to read and answer these questions: a. What connections can you make to what we have learned in class about teams and groups? b. What challenges did your group face? How did/does the group respond to these challenges? c. How does teamwork help your group achieve high-performance? ELITE TEAMS GET THE JOB DONE TEAM-BASED MANAGEMENT IS A LOT HARDER THAN IT LOOKS. HERE'S WHAT COMPANIES CAN LEARN FROM HIGHPERFORMANCE GROUPS OUTSIDE THE CORPORATE WORLD. By KENNETH LABICH REPORTER ASSOCIATE ERIN M. DAVIES Forbes Magazine, February 19, 1996 Section One – Everyone Reads This Section WEIRD FACT OF LIFE: for every problem we face, someone has come up with a solution way too slick to be true. So we've got fat-free mayonnaise that tastes like rancid yak butter, and let's not talk about bald guys who spray-paint their skulls. In the corporate world, there's that supposed miracle cure for ailing organizations--team-based management. The notion hasn't been a total bust; freewheeling, egalitarian teams have worked wonders at companies like Boeing, Volvo, HewlettPackard, and Federal Express. But the story's a sad one at more and more outfits that have taken up the cause. Here's how a team leader from American President Companies, responding in a focus group conducted by Forum Corp., put it: "A team is like having a baby tiger given to you at Christmas. It does a wonderful job of keeping the mice away for about 12 months, and then it starts to eat your kids." At the heart of the problem, say most management imams versed in the subject, is simple human nature. All too often team leaders revert to form and claim the sandbox for themselves, refusing to share authority with the other kids. Everyone else, meanwhile, sets to bickering about peripheral things like who gets credit for what the team produces. Old habits cling to life. Yet we've all come across teams outside the corporate realm that have beaten such problems. Like Justice Stewart watching naughty movies, we know the real stuff when we see it. The Chicago Bulls run a full-court fast break, capped by a thunderous Scottie Pippen dunk. A police SWAT team circles in on some crazed maniac barricaded inside a house. U.S. Army engineers slap together a pontoon bridge over a swollen river in Bosnia. You can't watch such elite, high-performance teams operate without wondering what these people know that so many of their corporate counterparts have yet to learn. In search of that very answer, FORTUNE spent time with seven highly successful, decidedly uncorporate teams and their leaders this autumn and winter. What we found, in each case, is that success at the highest level has been hard won. All of these elite groups think about and talk about working together all the time. Some of the groups we visited perform together almost without individual egos, like some multiheaded organism, but none of them got to that place without fierce effort--or hope to remain there without intense vigilance. On a trip to the U.S. Navy SEAL training base near San Diego, we saw how effective teams can be when everyone has an overriding compulsion to excel. 7 From the offensive linemen of the Dallas Cowboys, mammoth athletes who labor in virtual anonymity, and from the four world-class musicians who form the Tokyo String Quartet, we learned the value of resisting the egotism rampant in their fields. Anson Dorrance, the driven coach of the University of North Carolina women's soccer team, made a strong case for taking the trouble to discover what motivates each individual he leads. In Houston, the men who capped the raging Kuwaiti oil wells after the Gulf war testified to the power of group trust and absolute loyalty. The emergencytrauma team at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston showed how a flexible team switches leaders seamlessly, depending on the crisis at hand. Racecar team owner Richard Childress, who has slowly put together the most potent crew on the Nascar circuit, provided perhaps the most crucial lesson of all: if you want to build a great team, you'd better learn to be patient. Section Two – Navy SEALs HELL WEEK BEGINS at sundown on Sunday, at the end of the fifth week of training. The U.S. Navy SEAL recruits have already been through one of the most punishing physical and mental regimens ever devised, but for the next five days all that will seem like nothing. They will run endless miles, wearing boots, over sand. They will swim endless miles in the cold night waters of the Pacific. They will paddle rubber boats for hours, run a daunting obstacle course over and over, perform grueling calisthenics using 300-pound logs while instructors scream insults at them. During the five days of Hell Week, they will be allowed a total of perhaps four hours' sleep. After a couple days of this, hallucinations are common. Captain Steve Ahlberg, 45, a SEAL and now deputy chief of staff for the Navy's special warfare command, recalls seeing a giant figure walking across the water as he and his crew paddled along in their rubber boat during his Hell Week. He pointed out the phenomenon to his boat mates, and they all seemed to find it unremarkable. Lieutenant junior grade Jeff Eggers, a 24-year-old former Rhodes scholar who entered SEAL training this summer, recalls reaching some dark night of the soul during his Hell Week. His boat was being battered by eight-foot waves as he and his mates tried to get out to sea, and some of the crew began to lose it. "It brought me all the way down, and I had to climb back up to survive," says Eggers. Says chief boatswain's mate Pat Harwood, a chiseled, veteran SEAL now working as an instructor at the unit's seaside compound at Coronado, near San Diego: "The worst thing about Hell Week is that there are no parameters--you just don't know when the agony will end, and it really messes with your mind. I like to say that to get through this kind of challenge you need to have a black heart, meaning you are the sort 8 of person who will do anything--anything--to get where you need to go." And that's the point. Hell Week weeds out recruits who can't or won't make a total commitment to the group; about 30% of the trainees typically drop out during the five days. Says Rear Admiral Raymond Smith, the Navy's special-warfare commander: "We are talking here about a seminal event, something that is at the core of our vetting process." The first phase of training that climaxes with Hell Week is followed by seven weeks of rigorous underwater training, another nine weeks of weapons and explosives work, and then the three-week Army parachute-jumping course at Fort Benning, Georgia. After all that, the recruit must prove himself with an active SEAL unit during a six-month probationary period. Only about three of every ten recruits, all of whom had to pass tough physical standards even to begin training, eventually become SEALs. (The acronym refers to these commandos' all-terrain expertise: sea, air, land.) There are a total of about 500 SEAL officers and 1,800 enlisted men. The one impossibility is predicting who will stay the course. You can spot a few musclemen around the campuslike Coronado compound, but most of the commandos are of normal build and seemingly normal temperament. The best athletes, the fastest and strongest of the group, are sometimes the first to quit; one world-class triathlete walked away within the first few days of training this autumn. One surefire way to wash out, say all the SEALs, is trying to get by without the help of fellow recruits. Says Eggers: "If you are the sort of person who sucks all the energy out of the group without giving anything back, then you are going to go away." That sense of all-out teamwork is carried through in the field. SEALs never operate on their own, and their sense of identification with the group is all but total. One great source of unit pride is that no dead SEAL has ever been left behind on a battlefield. A few of the SEALs' more spectacular feats have become public. During the Vietnam war, three SEALs--including current U.S. Senator Robert Kerrey--won the Congressional Medal of Honor, and 12 more were awarded the Silver Star, all for acts of conspicuous bravery. More recently a SEAL named Howard Wasdin won a Silver Star in Somalia for repeatedly returning under fire to pick up fallen comrades, despite the multiple gunshot wounds he had suffered. Much of the SEALs' work overseas is--for them-relatively routine: teaching Namibian game wardens how to track down poachers, training Singaporean army regulars to combat potential terrorists. But clandestine, highly classified missions take place all the time. At any given moment groups of SEALs may be out in the field doing jobs that are never reported publicly. A rebel group is preparing to ambush a food convoy heading for a refugee camp in Rwanda; the only bridge the rebels can use to reach the convoy suddenly blows up. A Libyan trawler, lying in port before trying to run the Red Sea blockade against Iraq, mysteriously explodes. A band of drug smugglers is ambushed in the Colombian jungle. When you meet these people, the cliche is very true: You are glad they are on our side. Section Three – Dallas Cowboys THE PRESS IS ALLOWED into the Dallas Cowboys locker room at midday on most Wednesdays, and it can be a dubious privilege. Players in various states of undress wander in and out, chatting with one another in front of their cluttered cubicles and carefully ignoring the cluster of reporters and TV crews milling around in the center of the large square room. On this particular autumn Wednesday, a break in the tedium occurs only when superstar defensive back Deion Sanders saunters in and declares himself willing to speak. The reporters close in as Sanders points the Nike logo on his cap at the nearest lens, analyzes his new Pepsi contract, and critiques his own performance on the previous night's David Letterman show. When a reporter poses a question about the next Cowboy opponent, the Philadelphia Eagles, Sanders appears to be annoyed. The mob is so entranced by Deion's fandango that hardly anyone notices when several of the Cowboys' offensive linemen heave into view on the other side of the room. It is a remarkable sight. These are huge men, each at least six-three and 300 pounds. They can seem as nimble as cats on the field, but their great bulk seems inappropriate anywhere else. They don't so much walk as glide majestically, like tall ships entering a harbor. Playing the offensive line is a largely anonymous profession, no matter how good you might be at it. Quarterbacks, running backs, wide receivers, even defensive linemen gain far more notice. The Cowboy starters on the offensive line--tackles Erik Williams and Mark Tuinei, guards Larry Allen and Nate Newton, center Ray Donaldson (injured late in the season and replaced by Derek Kennard)--form one of the finest such NFL units in years, yet only the most rabid fans know their names. Happily, they wouldn't have it any other way. These modest behemoths get their greatest satisfaction from quietly doing their jobs. Accordingly, Tuinei and Allen seem a bit startled when a reporter approaches them to ask a few questions. Allen, a second-year, 325-pounder, mumbles a platitude or two and wanders off, no doubt in search of a serious lunch. Tuinei, a towering 6-foot-5 native Hawaiian and 13-year veteran, hangs in a bit longer. "Me and the other guys are like a family," he says. The anonymity of playing on the offensive line doesn't bother him a bit, he adds. He says he and his colleagues are especially proud that opponents have been able to penetrate their protective curtain and dump quarterback Troy Aikman on his fanny only about once per game this season. "That's what makes us feel good," he says. "Not talking about how terrific we are." Offensive line coach Hudson Houck, 53, a balding, highly enthusiastic gentleman who has been working with massive athletes like these for more than two decades, is far less shy about singing the unit's praises. Says he: "They are a team within a team, the best I've ever been around." Crafty veterans Tuinei and Newton have been particularly adept at integrating younger players like Williams and Allen into the system, says Houck. Anyone who doesn't work hard all the time is shunned. Donaldson, a durable, experienced player who came over from 9 Seattle this season, was accepted immediately when he showed the right attitude at practice. To appreciate fully just how effective the quintet can be, says Houck, you have to watch them pull off a slant play, the classic running maneuver that has helped back Emmitt Smith lead the league in rushing several times in recent years. An opportunity to do just that came the following Monday when the Cowboys took on the Eagles. The play was called late in the first quarter, and Tuinei and Newton, working on the left side of the line, drove their opponents back and away from the middle of the action. Williams, at right tackle, did the same to his man. Donaldson and Allen, meanwhile, doubleteamed the right defensive tackle for an instant, before Allen slipped his block and took out the opposing middle linebacker. All eyes were on Smith as he burst through the gap created by the various blocks for a long gain. You had to be looking for the small signs of fulfillment-a head butt here, a high-five there--that the offensive linemen allowed themselves as they moved back into the huddle. Section Four – Toyko String Quartet FOR THE TOKYO STRING QUARTET, widely recognized as one of the world's finest musical ensembles, a particularly satisfying moment came in 1993. The group--violinists Peter Oundjian and Kikuei Ikeda, cellist Sadao Harada, and violist Kazuhide Isomura--had been performing a series of Beethoven concerts at La Scala, the opera house in Milan. On the final night of the series, the four suddenly found themselves playing with greater fluency and feeling than ever before. They had completely left their individual selves and become one with the music. The audience, sophisticated musically, was soon transported as well. When the final notes sounded, the crowd maintained an awestruck silence for perhaps 15 seconds before exploding into cheers. "I was crying, and then I looked over and saw everyone else was crying as well," says the impish Isomura. "It was extremely emotional." Such moments of transcendent unity may come rarely, but members of the quartet, like those on other elite teams, work hard to keep their individual egos in check. Says Harada: "We don't think about who gets to show off their great sound, their great technique. We must project as one and put forth the quartet's musical personality." The group has found it's not always easy to stifle their egos, especially since each of the four is skilled enough to be considered a virtuoso soloist. It helps that somewhere between 200 to 300 great classical pieces have been written for chamber groups, far more than any stringed-instrument soloist could hope to encounter; the richness and variety of the repertoire make it easier to find fulfillment when the rigors of constant travel and incessant rehearsal wear them down. Because they have played together for decades, the three Japanese members of the quartet long ago developed natural ways of blending their skills. Their moods, talents, preferences--all are known territory. For a team in a profession that demands continuous innovation, the downside of such lifelong familiarity could be a sort of creative complacency. But the quartet was rescued from that fate in 1981 when Canadian Peter Oundjian joined up after the original first violinist dropped out. Oundjian brought an outsider's perspective to the group, questioning everything from musical selections to tour destinations. With less flexible teammates, the group's chemistry might have been destroyed by such an intruder. Instead, the mix has been enriched. Says Ikeda: "Because Peter brought with him a fresh approach, we have been able to see ourselves more objectively. We began to question everything along with him, and it's been continually challenging. This is what people should want in their work lives." Section Five – UNC Women’s Soccer ONE EVENING IN 1979, soon after he had taken over as coach of the University of North Carolina women's soccer team, Anson Dorrance was passing time by reading Pat Conroy's novel The Great Santini. Dorrance found himself stirred by the hypermacho dialogue of the title character, a Marine 10 Corps pilot, and he thought he might fire up his players the next day by passing along some of the rhetoric that had so moved him. "So I came to practice and started yammering about releasing your inner fury and eating life before it eats you," he says. "It was a disaster. The women just sat there, staring at me with blank faces." He has kept his reading preferences to himself ever since. Dorrance, 45, a strikingly intense, dark-haired man who was himself a star UNC soccer player, clearly learned his lesson exceedingly well. Over the past 17 seasons he has put together perhaps the most dominant college athletic program in history. His women's teams have compiled an extraordinary 34810-10 collegiate record since 1979, and this year's team narrowly missed taking UNC's tenth straight NCAA championship. Dorrance traces much of that success to specific motivational techniques he has developed over the years. With women, he has found, the key is finding what will trigger their self-confidence. Entering a prestigious program like Carolina's, even the best high school athletes will question their ability. "You go from being the best around to a situation where everybody was the best around," says Robin Confer, a high-scoring sophomore forward from Clearwater, Florida. To overcome any nagging doubts they may have about their talent, Dorrance works his charges ferociously at preseason practices. They will know that at least they have outtrained their opponents, he reasons. Then comes another problem, says Dorrance: Once women begin to bond with teammates, they tend to lose their competitive edge. Says he: "Men compete naturally--we'd rather beat the hell out of a friend than an enemy. Women prefer not to compete against people they like." To counter that trait, Dorrance and his assistants rate every player's performance on every drill during practice, and put out updated rankings each week. "The practices become like war," says Angela Kelly, a star on UNC's 1994 championship team. None of his little tricks will work if he doesn't establish a personal relationship with each player, says Dorrance. He says that men respond to leaders who demonstrate strength and competence, while women want to experience a leader's humanity. They do their best only if they believe they have a personal connection to the leader. This sense of connectedness goes well beyond coach-player relations. The players themselves maintain an intricate network of relationships that allow them to handle the pressures of maintaining the school's outrageous record of success. The women are particularly sensitive to the internal rhythms of the team; if two players are feuding, the whole group is thrown out of whack. "When you first get here, you don't understand the bonds you have to build," says Staci Wilson, a sophomore defensive whiz from Herndon, Virginia. "You really do end up playing for each other." Section Six – ER at Massachusetts General THE CALLS STARTED coming in just before two in the afternoon that autumn Monday. Two feuding families from Boston's North End had held a wild shootout in a Charlestown diner. At least five men were down, and the ambulances were rolling toward the emergency room at Massachusetts General Hospital. As it turned out, four of the men died before reaching the hospital, and only one had to be treated. The place was a zoo nonetheless, with the press outside howling for news of the survivor and a dozen outraged relatives roaming the hallways. A couple of days later you could still see the hole someone had punched in the waiting-room wall. That was by no means a normal day for Mass General's emergency-trauma team. "We get a lot more stabbings than shootings," says registered nurse Ray Bisio, a nine-year veteran of the service. But things stayed on an even keel because everyone knew their job and continued to perform. Somewhere around 200 patients show up daily at the emergency room at Mass General, generally acknowledged to be one of the world's finest teaching hospitals. About one-third of those patients will be admitted, and a score or so of the worst cases, those whose well-being or lives are in serious jeopardy, will wind up in the trauma center. There, they will be stabilized and usually moved on to surgery or the intensive-care unit. The flow of sick and injured--and the stress of treating them--never ends. On holidays like the Fourth of July, it seems that half of Boston is blowing off extremities with fireworks. The whole town seems intent on slamming cars into brick walls on New Year's Eve. The importance of seamless role-playing is dramatically evident when a gurney rolls into the small, brightly lit trauma center. A triage nurse has already determined that the patient is in big trouble, so there is never any time to lose. A team of doctors, nurses, and technicians comes together, seemingly by some strange kind of osmosis, and moves silently 11 to the patient's side. Each person begins a task-talking to the patient, running an IV, checking out a wound, hooking up a machine. Someone soon takes charge and plots a strategy for treatment. Usually a doctor, an attending physician or a senior resident, takes the lead, but at Mass General the direction can come from an intern or a nurse particularly well versed in an applicable field. "Nobody bosses everybody around," says attending physician Frederick Volinsky. "If someone has a thought that's useful, we are open to suggestions." The key point is that someone has to take on the responsibility--and live with the consequences. Says Alasdair Conn, the genial, 48-year-old Scotsman who presides over the trauma team as chief of emergency services: "Making a decision, even a wrong decision, is better than not making one at all." The quandaries just keep coming. An 84-year-old woman with a history of breathing problems is wheeled in. If you hook her up to a respirator, she may be stuck on one for life. If you don't, she may die. A young man, just 24, has fallen off a roof onto his back. He seems all right, but if a subtle spine injury isn't recognized he could end up in a wheelchair. The stress can be unbearable for some, but the team players at Mass General take solace in their professionalism, in knowing their roles and performing at the highest level. Conn says he looks for people who have some outside interest--sculling, numismatics--that they can use to escape the mental rigors of their work life. Maryfran Hughes, manager of the 55 to 60 nurses required to staff the hospital's various emergency services, says an adaptive personality can be as important as sheer competence. Says she: "People have to deal with situations where they have no control." Section Seven – Boots & Coots Oil Well Firefighters IT CAN HAPPEN anytime, for a hundred different reasons. A spark from a rock striking metal. Static electricity from clothes or work boots. Any kind of mistake or mischance and it's all over. For Joseph Carpenter, Martin Kelly, and Danny Strong, veteran [firefighters] from the Houston firm Boots & Coots, the end came at 3:15 in the afternoon this past June 10. The three were working on an out-of-control oil well in the Syrian desert, about 25 kilometers east of a town called Deir ez Zor. The blowout was underground, and the Houston well cappers had contained the surface oil in a large pit and were drilling a relief shaft to stabilize pressure below the crack. There was no reason to expect the sudden explosion at the wellhead that ended the three men's lives. A few months later a noticeable gloom still clings to the men who occupy the modest Boots & Coots headquarters in north Houston. Like other elite teams, these [firefighters] draw strength from the high-tensile bonds of trust and loyalty they have developed over the years. The loss of three brethren was a hard blow. "It's more or less natural to have a special thing with the other guys," says James Tuppen, 38, a Boots & Coots senior firefighter. "You spend a [darn] sight more time with them than you do with your own family, and your life is in their hands all the time." Tuppen, a slim, sandy-haired man, and his burly partner, David Thompson, 42, have taken over 12 management of their enterprise from the semiretired founders, Asger "Boots" Hansen and Edward Owen "Coots" Matthews. Those two learned this curious trade alongside the legendary Red Adair, now retired as well. Only a few dozen people on the planet can be called experts at controlling blowout wells, and Tuppen and Thompson, along with affiliated engineer John Wright, are among the most experienced. About 20 to 25 times in a normal year the phone rings in Houston, and one of the senior [firefighters] gathers up a team and heads off to some oil-soaked site, as close as west Texas or as far away as east Africa. They never know what they will find at a job site; conditions are usually primitive and often dangerous. They may wind up in Nigeria, trying to cap a well while keeping an eye out for armed bandits. Or in South America, dealing with obsolete equipment and hostile government officials. Or on a platform in the North Sea, coping with 50-foot waves and subzero temperatures. Then there is the food. Says Tuppen: "I remember down in Venezuela one time when they gave us some stuff to eat that was crawlin' with bugs. First few days, I just threw it away. After that, I scraped off the bugs and ate it. After a couple of weeks, I ate it bugs and all--for the protein." He adds: "It's sort of like the farmer who is feeding his dog a head of cabbage when a neighbor stops by. 'I didn't know that dog ate cabbage,' says the neighbor. 'He didn't at first,' says the farmer." obstacles. Says Tuppen: "We put out 128 of the baddest sons of bitches over there." The world at large became aware of the Texans' exploits back in 1991-92, when Saddam Hussein chose to ignite more than 700 Kuwaiti wells prior to his troops' retreat into Iraq. Boots & Coots was one of the first firms called in to contain the blazes after the war, and the company's [firefighters] were handed some of the toughest jobs because of their experience. The fires themselves weren't the main problem, though temperatures often topped 3,000¡ F. at the wellheads. As Thompson explains it, "When a well is on fire, it's already done the worst it can do." More troubling were the land mines and unexploded shells scattered about the oil fields, the lack of water to damp down the flames, and the scarcity of heavy machinery and other equipment. In the end, the Boots & Coots crews overcame the various What the Texans weren't ready for was the torrent of publicity that followed their feats in the Gulf. Suddenly, hundreds of resumes came pouring in. Most of them went unread, for these [firefighters] are fully aware that theirs is a craft for a very few. Thompson talks about a neighbor who bugged him repeatedly for a shot at a job. "I finally said all right, and the guy quit on me three times the first day," he says. "This is hot, dirty, nasty work." The company maintains a core staff of about ten firefighters, and Thompson and Tuppen say they are unlikely to add anyone they haven't known for years and brought along slowly, teaching him one trick at a time. There's too much on the line for all concerned, too much at stake to take on someone who hasn't earned their trust. Section 8 - NASCAR IN THE FLASHY, high-profile world of professional stock-car racing, no team-builder has bided his time better than Richard Childress. A brusque, broad-faced man from Winston-Salem, North Carolina, Childress, 50, was a moderately successful driver during the 1970s and early 1980s. But he has found his gear as an owner-entrepreneur, building the sport's most dominant crew. Since hooking up with top driver Dale Earnhardt in 1984, Childress has taken home six Winston Cup championships, the sport's top prize. In 1995, Childress's GM Goodwrench team finished a close second after digging a deep hole with early season crashes. Taking a cue from his own slow climb, Childress looks for young talent that he can mold to his team's needs. "I'd rather train them our way than try to break old habits," he says. One team member who fabricates new body parts had been making wood stoves. Childress found a top engine man doing scut work at a Chevy dealer. Nearly all team members start at the bottom-cleaning up after the mechanics in the garage, running errands. Even when they get to go on the road with the team, they are assigned to menial tasks like stacking tires and filling water bottles. All the while, they are being judged less for their performance than for their ability to work with the team. Says Danny "Chocolate" Myers, a Childress team member since its inception: "Attitude is more important than expertise--you've got to have people who won't let you down." The employees who don't make the cut are usually those who won't take the time to master the team's values and mores, according to team crew chief David Smith. "They come in with a self-centered attitude, livin' in the 'me' world," says Smith, who has worked his way up the team ladder since 1981. One true test of any racing team's mettle is the facility of its pit crew. Winston Cup races are often settled by fractions of a second, and any delays in the pit can blow away a team's chances. A top crew-seven men over the wall working on the car itself, another eight to ten on the other side handing them things and clearing away equipment--can change all four tires, power-pump 21 gallons into the tank, clean the windshield, and give the driver a drink of water, all in under 20 seconds. More sensitive maneuvers like adjusting tire pressure or changing the aerodynamics of the front end take more time, but not much more. We are talking here about teamwork at a rarefied level, a swarm of people acting as one. These folks have checked their self-interest back in the garage somewhere and moved to another zone. It's a state in which team members--be they musicians, commandos, or athletes--create a collective ego, one that gets results unattainable by people merely working side by side. It's all about humility, of course. Is that why it's such a scarce thing in the business world? 13 Worksheet - Can You Manage This? Last month, Carlos Allgood was promoted from word processing associate to word processing supervisor. The former supervisor was being transferred because she wasn’t able to get sufficient production from the word processing group. Carlos has been promoted because the department head, Lyle Waggoner, believed Carlos was a natural leader, knew the people in the group well, and knew the tricks they used to keep production down. Lyle was confident in Carlos’s abilities and willing to support his efforts. Lyle was right. Carlos did know the tricks. In fact, he started many of them! The work group practiced their tricks, not because they disliked their supervisor, but because they all thought it was fun and a challenge to outwit her. For example, they used signals to let each other know when she was coming so they would all look like they were hard at work. Then they would take it easy again when she left. They’d also pretend not to understand some new procedure so she’d go to great lengths to demonstrate and explain it. That way, they could stand around instead of work. They would complain to each other about working conditions, even though, Carlos knew, there was no justification for their complaints. At lunch, they’d ridicule the company and plan new ways to harass their supervisor. To them, it was a big joke. Now Carlos is the one who’s on the outside of the group, and the jokes are not so funny. He is determined to convince the group to work for the company, not against it. He knows how smart and talented this group really is and how loyal they are to each other. He believes they could produce a well above-average product if they are properly motivated. Of course, now that he’s the boss, his former colleagues are rather cool to him. That doesn’t bother him; he thinks he can overcome that in a few weeks. What does worry him is that Linda Allen has taken over as chief, and now they are trying to trick Carlos like they tricked their old supervisor. 1. Did Lyle make a good choice when he promoted Carlos? Why or why not? 2. What suggestions would you make to Carlos to turn this group into a team? 14 Worksheet – Cohesion or Dysfuntion? Directions: Consider a group that you’ve worked with for a school project. Then answer the questions. 1. What norms did the group have? 2. What roles were present? 3. How much conflict did the group experience? 4. Which of the sources of conflict presented in this chapter were present? 5. Which conflict handling styles did each group member have (list the member, the style, and which behaviors were demonstrated that support your assessment of their style). 6. Finally, what could you have done, specifically, to stimulate more conflict in your group? 15 Chapter Review General Questions 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. How do groups and teams differ? Answer in detail. Why is it important for a manager to know and at times “manage” informal groups? List the four purposes of teams and provide an example of each. How are quality circles and self-directed teams related? Summarize each of the stages of group and team development. What are the things a manager should consider when transforming a group into a team? What eight things can a manager do to build cohesive teams? What is the optimal team size? Define the two types of team roles. List two reasons why norms are enforced. Compare and contrast negative and constructive conflict. Summarize what happens to an organization when it experiences too little or too much conflict. Answer one of the following: a. Have you ever experienced groupthink? Describe your experience. b. Have you ever experienced constructive conflict? Describe your experience. Vocabulary Review Directions: Answers may be used only once. A. Adjourning F. Formal B. Conflict G. Informal C. Cross-functional team H. Maintenance D. Dialectic methods I. Negative E. Division of labor J. Norming K. L. M. N. O. Performing Programmed Quality circles Self-managed teams Storming _____ 1. A role-playing criticism to test whether a proposal is workable. _____ 2. Characterized by the emergence of individual personalities and roles and conflicts within the group. _____ 3. Consists of small groups of volunteers or workers and supervisors who meet intermittently to discuss the workplace and quality-related concerns. _____ 4. Group established to do something productive for the organization and is headed by a leader. _____ 5. Group formed by people seeking friendship. _____ 6. Groups of workers who are given administrative oversight for their task domains. _____ 7. Involves resolving conflicts, developing closer relationships and emerging unity and harmony. _____ 8. Known as a relationship-oriented role. _____ 9. Process in which one party perceives that its interest are being opposed or negatively affected by another party. _____ 10. Team staffed with specialists pursuing a common objective. _____ 11. Type of conflict designed to elicit different opinions without inciting people’s personal feelings. _____ 12. Type of conflict that hinders the organization’s performance and threatens its interests. _____ 13. When members concentrate on solving problems and completing the assigned task. _____ 14. When members prepare for disbandment. _____ 15. When the work is divided into particular tasks that are assigned to particular workers. 16 Multiple Choice _____ 1. Which of the following is one of the disadvantages of large teams? a. Division of labor c. Fewer resources b. Lower morale d. All of the above _____ 2. All of the following are ways managers can enhance team cohesiveness except: a. Keep the team small b. Encourage interaction c. Regularly update the team’s goals d. Make sure only certain members have a “piece of the action” _____ 3. All of the following are reasons for enforcing norms except: a. To help the group survive b. To clarify role expectations c. To help individual avoid embarrassing situations d. To help the group stick together _____ 4. Which of the following is a symptom of groupthink? a. Invulnerability b. Illusion of unanimity c. Rationalization d. All of the above _____ 5. Which of the following is not a cause of conflict? a. Competition for scarce resources b. Time pressure c. Clear job boundaries d. Individual differences can’t be resolved _____ 6. Which of the following statements regarding conflict is true? a. There can never be too much conflict b. Conflict is always negative c. Too little conflict leads to indolence d. Too much conflict leads to social loafing _____ 7. Which of the following is NOT a device for stimulating constructive conflict? a. Spurring the competition among employees b. Bringing in existing employees for different perspectives c. Using non-programmed conflict d. Changing the organization’s structure so that it embraces conflict _____ 8. What can teamwork achieve? a. Increased costs b. Increased destructive internal competition c. Increased speed d. Less workplace cohesiveness _____ 9. Which of the following is true regarding the differences between groups and teams? a. They don’t differ. b. Groups are freely interacting with a common goal and teams have complementary skills and commitment to a common purpose. c. Teams are formal and groups are informal. d. Teams are larger than groups. _____ 10. Which of the following is true regarding team size? a. Smaller teams have better interaction. b. Smaller teams have lower morale. c. Larger groups produce possibly less innovation. d. Larger groups lead to unfair work distribution. 17 True and False T F 1. Self-censorship is a symptom of groupthink. T F 2. You can prevent groupthink by allowing criticism and other perspectives. T F 3. Norms are enforced to help individuals embrace embarrassing situations. T F 4. Advice teams are quality circles. T F 5. A group is a collection of people with complementary skills who are committed to a common purpose. T F 6. A formal group is a group established by the organization. T F 7. The dialectic method is a role-play criticism to test whether a proposal is workable. T F 8. Inconsistent goals can lead to conflict. T F 9. Too much conflict leads to indolence. T F 10. There is positive and negative conflict. T F 11. The best constructive teams are composed of people who did not know each other prior to joining the team. Matching Directions: Match the recommended manager actions to the stage of team development. _____ 1. Allow time for people to socialize A. Adjourning _____ 2. Emphasize lessons learned during a ritual celebration B. Forming _____ 3. Emphasize unity and help identify team goals D. Performing _____ 4. Empower members to work on tasks C. Norming E. Storming _____ 5. Encourage members to express ideas and voice disagreements Matching Directions: Match the statement to the conflict handling style. Place a star next to the style that is best. _____ 1. Let’s cooperate to reach a solution that benefits both of us. A. Accommodating B. Avoiding _____ 2. Let’s do it your way. C. Collaborating _____ 3. Let’s split the different. D. Compromising _____ 4. Maybe the problem will go away. E. Forcing _____ 5. You have to do it my way. 18