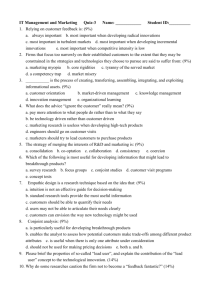

EMES - Heat and the City

advertisement