Lecture slides by Matt Ryan

advertisement

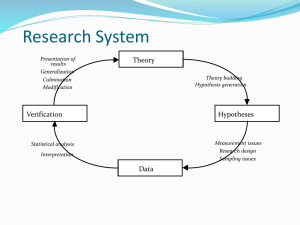

The experimental method 1 PAIR 1005 MATT RYAN Should we 2 …be control freaks? …be manipulative? …treat people who are the same completely differently? …be a bit random? The magic of the experiment 3 Intervention/treatment by the researcher in the process of data generation (precise manipulation). Control in the form of establishing a group to gather data from that have not experienced intervention. Magic 4 But in laboratory settings control can come through careful management of the variables that are in play. Random allocation of research subjects so that you can argue that in all features the two groups are the same, only difference is the intervention ‘Similar in all important respects’ The logic of experiments 5 Pre and post and other measurements Controlling for factors known to have an effect and unknown factors and so isolate impact of intervention variable Control group – nothing happens or placebo Repeat and replicate and get a firm handle on causality Formally at the head of the hierarchy 6 For positivists (and even post positivists) experiments are formally at the head of the ‘hierarchy of methods’ Lab and field approaches (and a role for ‘natural’ experiments) Is an artificial environment good or bad? 7 Lijphart (1971) in a seminal article in the American Political Science Review commented on how the purity of the comparison of a treatment and control group, backed up by random assignment, is seen as unrivalled in its capacity to deliver definitive results about causality. ‘The experimental method is the most nearly ideal method for scientific explanation, but unfortunately it can only rarely be used in political science because of practical and ethical impediments’ (Lijphart, 1971: 684-5) Too artificial? 8 The artificiality of the laboratory setting for social research that provides it with the ability to control extraneous influences also divorces those findings from the social context within which they have meaning. If we find people behave in a certain way in a(n)… experiment can we have any confidence that they will behave in the same way in their everyday lives? The answer is probably not (Peters, CP, 1998: 48). ‘Hawthorne effect’ (novelty problem) and measurement issues leading to ecological fallacy. Just not practical 9 For most research in the discipline there is little or no opportunity for experimentation-citizens are not likely to submit to very much experimentation on matters as crucial as the selection and management of their governments (Peters, CP, 1998:212). Can’t change the important things. We can’t exact randomly assign political systems or welfare systems. Ethical challenges 10 Treating people like rats? The harm principle Some experiments may involve misleading participants Blinding! Avoid or debrief them after the trial. Justifying the benefit and the need for the experiment The recent rise of experimentation 11 Always strong in psychology, major growth in economics and now in politics Growing influence of behavioural Economics and ‘Nudge’ theory. Strong field role in social policy and administration in education, employment, welfare, health and others areas Great tradition of policy experiments especially in the United States The rise of lab experiments (students as rats!) The use of the internet Varying messages Survey question research The smaller increase in field experiments Experiments can and do go wrong 12 Too high a risk? Problems in the heat of research 13 Lack of training among the staff involved in the intervention may create problems. Decisions made in the heat of the research may prove problematic to the experiment. Estimating effect size is always a challenge How many folks do you need in your study? Estimating the effects of system-wide reform can be particularly problematic using randomised trials because of contamination effects. There can be, for example, particular problems caused by the attrition of participants from programmes. Validity problems? 14 Internal validity: did the intervention have the impact that the experiment suggested? Sometimes the problem rests in the explication of the construct and sometimes it rests in the measurements and surrogates used to capture it. Response: Care, openness and challenge External validity: whether the validity of observations about cause and effect hold from the particular study across variation in persons, settings and measurement variables. Response: similar to that of other researchers, namely to argue for an accumulation of evidence. Why take the risk? 15 Experiments can support a dynamic between theory and evidence Enables social scientists to engage with issues that people care about Exploring microfoundations 16 Offers clarification for our models and theories Direct benefit in expanding the heuristics available to policy makers and social actors Delivers on relevance 17 Field experiments require engagement The need for flexibility and adaptability A test of practicality Opportunities abound 18 What we could in the Lab? What we could do in the field? But there will always be limits External validity in the lab Confounding factors in the field Variations on experiments 19 Natural experiments E.g. ballot ordering Quotas - Bhavnani Quasi-experiments E.g. Fishkin’s deliberative polls? Design experiments? And so? 20 Experimenters need to more explicit about their value- added Consider the prospects for quasi and natural experiments ( design experiments) Need to accept a mix of methods and continuing role for observational research The statistical method and the comparative method Experimental ethics 21 Cases e.g. Milgram, the ‘Strivers’ Withdrawal vs. attrition Ethics of offering incentives? My experience troubleshooting 23 Fun war stories.. Students Parishioners Tenants Experiments frame our thinking about causality using other methods 24 “Testing relationships between variables by keeping all other factors constant” the experimenters code that other methods try to replicate: The statistical method aims to ape experimental method by intervening after the data are created ( by holding some variables constant in order to test the impact of other variables) Random selection rather than random allocation. Comparative analysis Can drive the logic of temporal or spatial comparison when only smaller number of cases available Can influence case study selection Rational thought experiments: what if? BUT SOME REJECT THIS ASSIMILATION OF ALL METHODS TO THE LOGIC OF EXPERIMENTS