Sociology and Law

advertisement

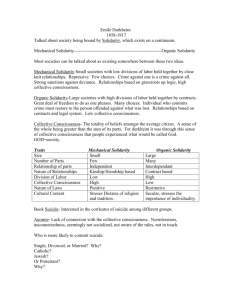

Sociology and Law Tuesday, 05 November 2013 Durkheim To explain a fact, study its cause and its function separately.Obviously, following from the basic rule, these functions and causes are, by definition, social and cannot be retrieved in the individual psyche, although he admits that human nature plays a part in social facts (as a kind of disturbing factor, but never as a cause). The rules to find function and cause are: the cause of a social fact lies in antecedent social facts, and the function of a social fact lies in the end it fulfills.In other words, social processes should be explained in terms of society itself (e.g. social volume and density). The Distinction of the Normal from the Pathological Science cannot decide what is good or evil for us, because it would be ideological, yet, on the other hand, science must justify itself.Durkheim sees the solution to this problem in the fact that science should ask and investigate what is actually, in a given society, good or desirable.Science is not evil or good but it can study evil and good. Here, Durkheim proceeds to do just that. Social facts are pathological when they disrupt the normal operations of social functions in a certain society. This, of course, can vary from society to society. Note Durkheim’s functionalist argument that the most widespread social forms are, in the long run and in the aggregate, the ones that survive (normality is therefore more common). Therefore, social facts can be pathological at some time in development (but not in the long run) because, and only when, they were at one time normal. Normality of Crime An example is the demonstration of the normality of crime. Crime is normal because it is observed, in some form or another, in all societies.It is not a demonstration of the wicked nature of man, but, on the contrary, a factor that shows the necessary integrative element in society what is normal in one society is not necessarily normal in another Above we indicated that Durkheim distinguishes different societies from one another. How does he make this distinction? This is the task of social morphology. Durkheim proposes to first identify the basic, crucial characteristics of societies, which can be identified in a study of the simplest of societies (this is why he undertook the study of Australian religions). This indicates the relevance of ethnographies for sociology.Therefore, he proposes to study the horde, i.e. a social formation which cannot be split up into any smaller social parts; the horde consist of individuals.Different hordes linked together form a clan. From here on, societies can be classified into social types, e.g. a simple replication of hordes or clans, a replication of these replications, and so on (see Division of Labor). Division of Labor Economic forces have lead not only to a functional differentiation of labor but also to differentiation processes in all other domains of society. Durkheim argues that this is the result of an evolution from mechanical to organic societies. Mechanical societies are composed of similar replicated parts (families, hordes, clans). Durkheim argues that in the course of history organic society made progress in the proportion to which mechanical society has regressed. Organic societies are made up of functionally different organs, each performing a special role.The collective consciousness of this social type has a different hold on the individual: the bonds to tradition and family are loosened, but the individual now has the social duty to specialize and to concentrate his range of activities.The collective consciousness in modern societies still has a hold on individuals, if only to affirm their individuality. Crime, Law and Punishment In the Division of Labor, Durkheim conceives law as a manifestation of the collective consciousness.Hence he uses as a measure for the development from mechanical to organic societies the evolution from repressive to restitutive law. Repressive law is characteristic for simple and ancient societies. Law is essentially religious law and infractions against it are immediately punished because they threaten the existence of the collectivity itself. Crimes that are not religious are less severely punished. The moral beliefs and justifications on which law and punishment are based are specific but not explicitly specified since every member of society knows them (the collective consciousness is identical to the individual consciousness).In modern societies only criminal law is still repressive: it serves the unconscious function of strengthening social solidarity. The nature of modern solidarity, however, changed and criminal law declined in favor of restitutive law. Punishment follows legal violations in a restitutive way so that the relations between individual and society are restored.Because individuals are more and more differentiated from one another (they have different professions), legal regulations are more abstract and general so they can still apply to all different individuals and provide the solidarity necessary for the cohesion of society: "That alone is rational that is universal. What defies the understanding is the particular and the concrete". Contract growth of commercial law is an index of organic social solidarity: it indicates the need to maintain relations between differentiated parts (analogous to the specialized functions of the organs of the body), which are backed up by society.In contract law, for instance, every contract "assumes that behind the parties who bind eachother, society is there, quite prepared to intervene and to enforce respect for any undertakings entered into". In organic societies it is therefore the state which becomes the organ of priority to direct the other organs (like the brain). Violating the rules of a contract between individuals is an offense against the state as the representative body of modern collective conscience Crime Penality Law In a later work Durkheim modifies his view of law and outlines two laws of penal evolution. The first law stipulates that "the intensity of punishment is greater the more closely societies approximate to a less developed type - and the more the central power assumes an absolute character".Durkheim thus reaffirms what he earlier argued in The Division of Labor: the collective consciousness is stronger in mechanical societies, more loosened in organic societies. He now explicitly links this evolution with the religious or secular nature of law. In primitive societies, the collective consciousness is essentially religious and so are their laws. In organic societies, the law is secularized to refer to some human interest, not an individually held interest but to mankind in general (analogous to the development of the collective consciousness). Any offense is an offense against another human and "cannot arouse the same indignation as on offense of man against God Crime Penality Law However, in the second part of the first law Durkheim states that the nature of political power also intervenes in the development of the intensity of punishment. The law does not always "automatically" represent the collective consciousness; it may be "distorted" by the political regime that determines its contents.An absolutist government which faces no counter-balancing social forces, in particular, may create and enforce laws which do not correspond to the collective consciousness: the laws may be repressive, even in a differentiated society characterized by a division of labor. However, Durkheim asserted, this is not "a consequence of the fundamental nature of society, but rather depends on unique, transitory, and contingent factors". The political society to be normal, therefore, should always be in concord with the development of the collective consciousness. Identity of mechanical society – represive sanctions Identity of Organic society – compenstion and contract