A Personal View of the Etiology of Preeclampsia

advertisement

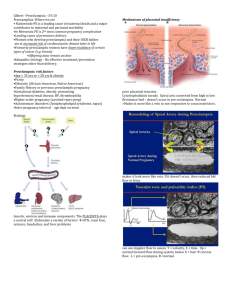

The Etiology of Preeclampsia 9 June 2009 Presented by Damon T. Cudihy, MD Mentor: Richard Lee, M.D. Goals of Project To survey and review recent literature proposing evidence for theories of pathogenesis of preeclampsia 2. To distinguish true causes of preeclampsia as opposed to mere bio-indices and epiphenomena 3. Regarding the etiology of preeclampsia, to 1. provide a biologically plausible theory that unifies the essential and validated findings of past and current scientific investigation. Questions to answer 1. 2. 3. What do we know about the burden of pre-eclampsia so far? Do we know enough to understand the cause of pre-eclampsia? With a better understanding of the cause of pre-eclampsia could we begin to prevent the disease and develop better treatments that will minimize the associated morbidity and mortality ? Background Diagnosis – Hypertension: SBP≥140 or DBP≥90 – Proteinuria: ≥0.1g/L (2+) in ≥2 random urine samples ≥4hrs apart; or ≥0.3g in 24hrs Disease burden – Affects 3-14% of all pregnancies worldwide (5-8% of pregnancies in the U.S.) Effect on mother and child – Leading cause of worldwide pregnancy-related maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity Spectrum of Preeclampsia Conception Failed implantation Early Placental Vascular dificiency Late Placental Dysfunction Spontaneous abortion Early onset Preeclampsia Preeclampsia Risk Factors for Preeclampsia Nulliparity Primipaternity Personal or family history (37% in sisters) Twin gestation (20, 70%) Molar pregnancy (70%) Maternal infection Chronic Hypertension Renal Disease Diabetes (50%) Androgen excess Obesity/Insulin Resistance Dyslipidemia Thrombophilias (Antiphospholipid, Protein C/S deficiency,AntithromMbin deficiency, Factor V Leiden, MTHFR) Condom use Donor sperm fertilization Non-smoking Pre-eclampsia as a risk factor: Cardiovascular disease Renal disease Insulin resistance Current Theories Associated with Etiology of Preeclampsia Immunologic phenomena Abnormal trophoblastic invasion Vascular endothelial damage Cardiovascular maladaptation Inflammation and oxidative stress Genetic predisposition Coagulation abnormalities Dietary deficiencies or excesses Model of Contributing Factors Preeclampsia Maternal factors Genetic Acquired Paternal factors Gestational factors Genetic Acquired Key Principles “Disease of first pregnancy” – 3-7% in nulliparas, 1-5% in multiparas – Primipaternity model Placental load association – Increased incidence and severity in multiple gestations and molar gestation Global Endothelial dysfunction Biomarkers for prediciton and detection of Preeclampsia the focus of most U.S. studies in past 2 years demonstrate preeclampsia as an antiangiogenic state resulting from overproduction of antiangiogenic factors Soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt-1) and Soluble Endoglin Circulating placental proteins – Inhibit angiogenesis and arteriolar vasodilation Excessive amounts may lead to systemic endothelial dysfunction causing preeclampsia screening test for preeclampsia? --MAYNARD, SHARON E.; et al. Soluble Fms-like Tyrosine Kinase 1 and Endothelial Dysfunction in the Pathogenesis of Preeclampsia. Pediatric Research. Review Issue. 57(5 Part 2):1R-7R, May 2005. --Levine, Richard J.;et al. for the CPEP Study Group Soluble Endoglin and Other Circulating Antiangiogenic Factors in Preeclampsia. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 62(2):82-83, February 2007. Pathophysiology of preeclampsia and resulting symptoms; EDFMD, endothelium-dependent flow-mediated vasodilation. From: WEISSGERBER: Med Sci Sports Exerc, Volume 36(12).December 2004.2024-2031 Clinical manifestations of pre-eclampsia All result from endothelial dysfunction at the various end organs in the body: – Systemic Arterial vasculature HTN, edema – Central Nervous System headache, visual changes, seizure – Hepatic system RUQ pain, HELLP – Renal system proteinuria, renal failure – Placental system IUGR, oligohyrdramnios, abruption Risk factors for pre-eclampsia A loosely defined grouping 1. 2. 3. Genetically inherited susceptibilities (maternal and paternal side) Conditions with known associations with endothelial dysfunction States affecting the immune-modulated placental cytotrophoblastic cell invasion of maternal spiral artery endothelium 1. Genetically Inherited Factors Both men and women who themselves were the born of a pregnancy complicated by preeclampsia are significantly more likely to be parents of a child with pre-eclampsia Baseline “fitness” of maternal endothelial function Maternal immune system function Particular genotype combinations between mother and child (or mother and father) associated with preeclampsia 2. Endothelial Dysfunction All clinical manifestations can be explained by endothelial dysfunction Most risk factors associated with endothelial dysfunction – all chronic disease risk before and after preeclampsia – role of infection, diet, exercise, and oxidative stress Pregnancy and preeclampsia as a physiologic endothelial stress test 3. Immune-mediated invasion and angiogenesis Accounts for remaining risk factors: nulliparity, primipaternity, condom use, IVF, twins, moles, and non-smoking Maternal immune system facilitates invasion of fetal extravillous cytophoblastic cells into the myometrium and arteriolar endothelium Accounts latest findings of anti-angiogenic factors associated with preeclampsia Grouping of Risk Factors for Preeclampsia 1. Genetic – 2. Personal or family history (37% in sisters) Endothelial dysfunction – – – – – – – – Maternal infection Chronic Hypertension Renal Disease Diabetes (50%) Androgen excess Obesity/Insulin Resistance Dyslipidemia Thrombophilias 3. Immune-mediated invasion and angiogenesis – – – – – – – Nulliparity Primipaternity Twin gestation (20, 70%) Molar pregnancy (70%) Condom use Donor sperm fertilization Non-smoking Pathophysiology of Preeclampsia 2 Stage process 1. Preclinical (≤20 weeks): – inadequate invasion of maternal spiral arterioles by fetal cytotrophoblasts insufficient maternal vascular remodeling and angiogenesis 2. Clinical (normally >20 weeks): – Oxidatively stressed/hypoxic placenta generalized systemic inflammatory response with release of anti-angiogenic factors, inflammatory cytokines, and trophoblast debris maternal syndrome Natural Killer Cells: Friend or Foe? Named for their cytotoxic action against virusinfected and tumor-transformed cells Paradoxically, NK cells play a key role in facilitating and stimulating the invasion of tumor-like fetal trophoblastic cells into the maternal vasculature. The dysfunction/dysregulation of decidual NK cells recocile the two leading theories: 1. Immune maladaptation 2. Insufficient invasion of the maternal spiral arteries by fetal trophoblasts Diagram of basic maternal and placental vasculature Normal vs Abnormal Vascular Remodeling of Spiral Arteries Future Directions Further clarification of the physiologic vs. pathologic interactions between maternal decidual NK cells and fetal extravillous trophoblasts Identification of genes involved with immune maladaptation Biomarkers as screening tools to target interventions to reduce risk Tx’s designed to boost extravillous trophoblastic invasion targeted to high risk women? Pharmacologic manipulation of NK cells to direct them in the pro-angiogenic pathway? Conclusion 1. 2. 3. Early maternal-fetal interface involving decidual/uterine NK cells and extravillous trophoblasts Healthy pregnancy requires NK cell stimulation of vascular invasion by fetal trophoblasts (an immune-mediated process) Inadequate vascular invasion by fetal cells leads to placental hypoxiaoxidative stressmaternal endothelial dysfunctionclinical signs and symptoms of pre-eclampsia “Therefore, one may state at least tentatively, that future collaboration between the obstetrician and immunologist should produce the needed diagnostic and therapeutic tools to place preeclampsia together with Rh isoimmunization as an interesting, but eminently treatable immunologic dysfunction.” --John Willems. The Etiology of Preeclampsia: A Hypothesis. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 50 (4), Oct 1977. References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. Report of the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.2000;183:S1-S22 ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins--Obstetrics. ACOG practice bulletin. Diagnosis and management of preeclampsia and eclampsia. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2002; 99:159. Sibai BM; Gordon T, Thom E, Caritis SN, Klebanoff M, McNellis D, Paul RH Risk factors for preeclampsia in healthy nulliparous women: a prospective multicenter study. The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.1995 Feb;172(2 Pt 1):642-8. Saftlas AF, Olson DR, Franks AL, Atrash HK, Pokras R Epidemiology of preeclampsia and eclampsia in the United States, 1979-1986. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.1990 Aug;163(2):460-5. Maternal mortality--United States, 1982-1996. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) 1998 Sep 4;47(34):705-7. Cunningham FG, Lindheimer MD. Hypertension in pregnancy. New England Journal of Medicine 1992 Apr 2;326(14):927-32. Walker J. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet 2000: 356(9237):1260-1265. South Africa Every Death Counts Writing Group. Every death counts: use of mortality audit data for decision making to save the lives of mothers, babies, and children in South Africa. Lancet 2008; 371:1294-304. Barton J, Sibai B. Prediction and Prevention of Recurrent Preeclampsia. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2008; 112:359-372. Harkskamp R, Zeeman G. Preeclampsia: At Risk for Remote Cardiovascular Disease. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences 2007. 334(4): 291-295. Thadhani R, Solomon C. Preeclampsia—A Glimpse into the Future? New England Journal of Medicine 2008. 359(8): 858-860. Wolf M, Hubel C, Lam C, Sampson M, Ecker H, Ness R, Rajakumar A, Daftary A, Shakir A, Seely E, Roberts J, Sukhatme V, Karumanchi A, Thadhani R. Preeclampsia and Future Cardiovascular Disease: Potential Role of Altered Angiogenesis and Insulin Resistance. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2004. Vol. 89, No. 12 6239-6243 Vikse B, Irgens L, Leivestad T, Skjærven R, Iversen B. Preeclampsia and Risk of End-Stage Renal Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2008. 359(8):800-809. Mogren I, Hogberg U, Winkvist A, Stenlund H. Familial occurrence of preeclampsia. Epidemiology 1999. 10:518. Esplin M, Fausett M, Fraser A, Kerber R, Mineau G, Carrillo J, Varner M. Paternal and maternal components of the predisposition to preeclampsia. New England Journal of Medicine 2001. 344:867. References (cont’d) 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. Hiby S, Walker J, O’Shaughnessy K, Redman C, Carrington M, Trowsdale J, Moffett A. Combinations of Maternal KIR and Fetal HLA-C Genes Influence the Risk of Preeclampsia and Reproductive Success. The Journal of Experimental Medicine 2004. 200(8):957-965. Saito S, Sakai M, Sasaki Y, Nakashima A, Shiozaki A. Inadequate tolerance induction may induce pre-eclampsia. Journal of Reproductive Immunology 2007. 76:30-39. Le Bouteiller P, Pizzato N, Barakonyi A, Solier C. HLA-G, pre-eclampsia, immunity and vascular events. Journal of Reproductive Immunology 2003. 59:219-234. Goldman-Whol D, Ariel I, Greenfield C, Hochner-Celnikier D, Cross J, Fisher S, Yagel S. Lack of human leukocyte antigen-G expression in extravillous trophoblasts is associated with pre-eclampsia. Molecular Human Reproduction 2000. 6(1): 88-95. Conde-Agudelo A, Villar J, Lindheimer M. Maternal infection and risk of preeclampsia: Systematic review and metaanlysis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2008. 198(1):7-22 Cines D, Pollak E,. Buck C, Loscalzo J, Zimmerman G, McEver R,. Pober J, Wick T, Konkle B, Schwartz B, Barnathan E, McCrae k, Hug B, Schmidt A, Stern D. Endothelial Cells in Physiology and in the Pathophysiology of Vascular Disorders. Blood 1998. 91(10): 3527-3561. LaMarca B, Gilbert J, Granger J. Recent Progress Toward the Understanding of the Pathophysiology of Hypertension During Preeclampsia. Hypertension 2008. 51:982-988. Robillard P, Dekker G, Chaouat G, Hulsey T. Etiology of preeclampsia: maternal vascular predisposition and couple disease—mutural exclusion or complementarity? Journal of Reproductive Immunology 2007. 76:1-7. Willems J. The Etiology of Preeclampsia. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 50:495, 1977. Shembrey M, Noble A. An instructive case of abdominal pregnancy. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1995. 35:220-221. Clark J, Niles J. Abdominal Pregnancy Associated with Toxemia of Pregnancy. Journal of the National Medical Association 1967. 59(1): 22-24. Kopcow H, Karumanchi A. Angiogenic factors and natural killer (NK) cells in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Journal of Reproductive Immunology 2007. 76: 23-29. Pfarrer C, Macara L, Leiser R, Kingdom J. Adaptive angiogenesis in placentas of heavy smokers. The Lancet 1999. 354(9175): 303. Egleton R, Brown K, Dasgupta P, Angiogenic activity of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: Implications in tobaccorelated vascular diseases. Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2008. Nov 14 [Epub ahead of print]. Redman C, Sargent I. Latest Advances in Understanding Preeclampsia. Science 2005. 308(5728):1592-1594. References (cont’d) 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. 36. 37. 38. 39. 40. 41. 42. 43. 44. Soundararajan R, Rao A. Trophoblast ‘pseudo-tumorigenesis’: Significance and contributory factors. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology 2004. 2:15 Sargent I, Borzychowski A, Redman C. Immunoregulation in normal pregnancy and pre-eclampsia: an overview. Reproductive Biomedicine Online 2006. 13(5): 680-686. Wiessgerber T, Wolfe L, Davies G. The Role of Regular Phyisical Activity in Preeclampsia Prevention. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2004. 36(12):2024-2031. Maynard, Sharon E.; et al. Soluble Fms-like Tyrosine Kinase 1 and Endothelial Dysfunction in the Pathogenesis of Preeclampsia. Pediatric Research. Review Issue 2005. 57(5 Part 2):1R-7R. Levine R, Lam C, et al. for the CPEP Study Group Soluble Endoglin and Other Circulating Antiangiogenic Factors in Preeclampsia. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 62(2):82-83, February 2007. Rana S, Karumanchi A, et al. Sequential Changes in Antiangiogenic Factors in Early Pregnancy and Risk of Developing Preeclampsia. Hypertension 2007. 50:137-142. Scholl T, Leskiw M, Chen X, Sims M, Stein T. Oxidative stress, diet, and the etiology of preeclampsia. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2005. 81:1390-1396. Moffet A, Hiby S. How Dose the Maternal Immune System Contribute to the Development of Pre-eclampsia? Placenta 2007. 28(21):S51-S56. Sargent L, Borychowski A, Redman C. NK Cells and pre-eclampsia. Journal of Reproductive Immunology 2007. 76:40-44. Hanna J, Goldman-Wohl D, et al. Decidiual cells regulate key developmental processes at the human fetalmaternal interface. Nature Medicine 2006. 12(9): 1065-1074. Chaouat G, Ledee-Bataille N, Dubanchet S. Immune cells in uteroplacental tissues throughout pregnancy: a brief review. Reproductive BioMedicine Online 2006. 14(20:256-266. Kwak-Kim J, Gilman-Sachs A. Clinical Implication of Natural Killer Cells and Reproduction. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 2008. 59:388-400. Hiby S, Regan L, Farrell L, Carrington M, Moffett A. Association of maternal killer-cell immunoglobuline-like receptors and parental HLA-C genotypes with recurrent miscarriage. Human Reproduction 2008. 23(4):972-976. Miko E, Szereday L, et al. The Role of Invariant NKT Cells in Pre-Eclampsia. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 2008. 60:118-126.