Basic PL/SQL Syntax Elements

advertisement

1

Basic PL/SQL Syntax Elements

1. PL/SQL Block Structure

In PL/SQL, as in most other procedural languages, the smallest meaningful grouping of code is

known as a block. A block is a unit of code that provides execution and scoping boundaries for

variable declarations and exception handling. PL/SQL allows you to create anonymous blocks

(blocks of code that have no name) and named blocks , which may be procedures, functions, or

triggers.

In the sections below, we review the structure of a block and focus on the anonymous block. We'll

explore the different kinds of named blocks later in this chapter.

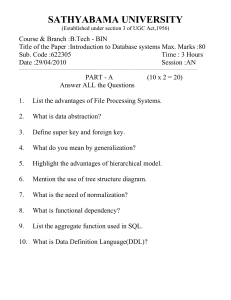

A PL/SQL block has up to four different sections, only one of which is mandatory. Figure

illustrates the block structure.

Figure. The PL/SQL block structure

Header

Used only for named blocks . The header determines the way the named block or program

must be called. Optional.

Declaration section

Identifies variables, cursors, and sub-blocks that are referenced in the execution and

exception sections. Optional.

Execution section

Contains statements that the PL/SQL runtime engine will execute at runtime. Mandatory.

Exception section

Handles exceptions to normal processing (warnings and error conditions). Optional.

1.2. Anonymous blocks

When someone wishes to remain anonymous, that person goes unnamed. The same is true of the

anonymous block in PL/SQL, which is shown in Figure : it lacks a header section altogether,

beginning instead with either DECLARE or BEGIN. That means that it cannot be called by any

other blockit doesn't have a handle for reference. Instead, anonymous blocks serve as containers

that execute PL/SQL statements, usually including calls to procedures and functions.

The general syntax of an anonymous PL/SQL block is as follows:

[ DECLARE

... declaration statements ...]

BEGIN

2

... one or more executable statements ...

[ EXCEPTION

... exception handler statements ...]

END;

Figure. An anonymous block without declaration and exception sections

The square brackets indicate an optional part of the syntax. You must have BEGIN and END

statements, and you must have at least one executable statement. Here are a few examples:

A bare minimum anonymous block:

BEGIN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE(SYSDATE);

END;

A functionally similar block, adding a declaration section:

DECLARE

l_right_now VARCHAR2(9);

BEGIN

l_right_now := SYSDATE;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE (l_right_now);

END;

The same block, but including an exception handler:

DECLARE

l_right_now VARCHAR2(9);

BEGIN

l_right_now := SYSDATE;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE (l_right_now);

EXCEPTION

WHEN VALUE_ERROR

THEN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('I bet l_right_now is too small '

|| 'for the default date format!')

END;

2. The PL/SQL Character Set

A PL/SQL program consists of a sequence of statements, each made up of one or more lines of text.

The precise characters available to you will depend on what database character set you're using. For

example , Table illustrates the available characters in the US7ASCII character set .

Table. Characters available to PL/SQL in the US7ASCII character set

Type

Characters

Letters

A-Z, a-z

Digits

09

3

Table. Characters available to PL/SQL in the US7ASCII character set

Type

Characters

Symbols

~!@#$%*()_-+=|:;"'<>,.?/^

Whitespace

Tab, space, newline, carriage return

Every keyword, operator, and token in PL/SQL is made from various combinations of characters in

this character set. Now you just have to figure out how to put them all together!

Keep in mind that PL/SQL is a case-insensitive language. That is, it doesn't matter how you type

keywords and identifiers; uppercase letters are treated the same way as lowercase letters unless

surrounded by delimiters that make them a literal string. By convention, the authors of this book

prefer uppercase for built-in language keywords and lowercase for programmer-defined identifiers.

A number of these charactersboth singly and in combination with other charactershave a special

significance in PL/SQL. Table lists these special symbols.

Table. Simple and compound symbols in PL/SQL

Symbol

Description

;

Semicolon: terminates declarations and statements

%

Percent sign: attribute indicator (cursor attributes like %ISOPEN and indirect

declaration attributes like %ROWTYPE); also used as multi-byte wildcard symbol

with the LIKE condition

_

Single underscore: single-character wildcard symbol in LIKE condition

@

At-sign: remote location indicator

:

Colon: host variable indicator, such as :block.item in Oracle Forms

**

Double asterisk: exponentiation operator

< > or != or

Ways to denote the "not equal" relational operator

^= or ~=

||

Double vertical bar: concatenation operator

<< and >>

Label delimiters

<= and >=

Less than or equal to, greater than or equal to relational operators

:=

Assignment operator

=>

Association operator for positional notation

..

Double dot: range operator

--

Double dash: single-line comment indicator

/* and */

Beginning and ending multi-line comment block delimiters

Characters are grouped together into lexical units, also called atomics of the language because they

are the smallest individual components. A lexical unit in PL/SQL is any of the following: identifier,

literal, delimiter, or comment. These are described in the following sections.

3. Identifiers

An identifier is a name for a PL/SQL object, such as a variable, program name, or reserved word.

The default properties of PL/SQL identifiers are summarized below:

Up to 30 characters in length

4

Must start with a letter

Can include $ (dollar sign), _ (underscore), and # (pound sign)

Cannot contain any "whitespace " characters

If the only difference between two identifiers is the case of one or more letters, PL/SQL treats those

two identifiers as the same. For example, the following identifiers are all considered by PL/SQL to

be the same:

lots_of_$MONEY$ LOTS_of_$MONEY$ Lots_of_$Money$

3.1. NULLs

The absence of a value is represented in Oracle by the keyword NULL. As shown in the previous

section, variables of almost all PL/SQL datatypes can exist in a null state (the exception to this rule

is any associative array type, instances of which are never null). Although it can be challenging for

a programmer to handle NULL variables properly regardless of their datatype, strings that are null

require special consideration.

In Oracle SQL and PL/SQL, a null string is usually indistinguishable from a literal of zero

characters, represented literally as '' (two consecutive single quotes with no characters between

them). For example, the following expression will evaluate to TRUE in both SQL and PL/SQL:

'' IS NULL

While NULL tends to behave as if its default datatype is VARCHAR2, Oracle will try to implicitly

cast NULL to whatever type is needed for the current operation. Occasionally, you may need to

make the cast explicit, using syntax such as TO_NUMBER(NULL) or CAST(NULL AS

NUMBER).

3.2. Literals

A literal is a value that is not represented by an identifier; it is simply a value.

A string literal is text surrounded by single quote characters, such as:

'What a great language!'

Unlike identifiers, string literals in PL/SQL are case-sensitive. As you should expect, the following

two literals are different.

'Steven'

'steven'

So the following condition evaluates to FALSE:

IF 'Steven' = 'steven'

3.3. Numeric literals

Numeric literals can be integers or real numbers (a number that contains a fractional component).

Note that PL/SQL considers the number 154.00 to be a real number of type NUMBER, even though

the fractional component is zero and the number is actually an integer. Internally, integers and reals

have a different representation, and there is some small overhead involved in converting between

the two.

You can also use scientific notation to specify a numeric literal. Use the letter "E" (upper- or

lowercase) to multiply a number by 10 to the nth powerfor example, 3.05E19, 12e-5.

Beginning in Oracle Database 10g Release 1, a real can be either an Oracle NUMBER type or an

IEEE 754 standard floating-point type . Floating-point literals are either binary (32-bit) (designated

with a trailing F) or binary double (64-bit) (designated with a trailing D).

In certain expressions, you may use the named constants summarized in Table as prescribed by the

Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) standard.

5

Table. Named constants for BINARY_FLOAT and BINARY_DOUBLE

Description

BINARY_FLOAT (32-bit)

BINARY_DOUBLE (64-bit)

"Not

a

number"

(NaN); result

BINARY_FLOAT_NAN

of divide by 0

or

invalid

operation

BINARY_DOUBLE_NAN

Positive

infinity

BINARY_DOUBLE_INFINITY

BINARY_FLOAT_INFINITY

Maximum

finite number

that is less

BINARY_FLOAT_MAX_NORMAL

than

the

overflow

threshold

BINARY_DOUBLE_MAX_NORMAL

Smallest

normal

number;

underflow

threshold

BINARY_DOUBLE_MIN_NORMAL

BINARY_FLOAT_MIN_NORMAL

Maximum

positive

number that BINARY_FLOAT_MAX_SUBNORM BINARY_DOUBLE_MAX_SUBNORMA

is less than AL

L

the underflow

threshold

Absolute

minimum

BINARY_FLOAT_MIN_SUBNORM

number that

AL

can

be

represented

BINARY_DOUBLE_MIN_SUBNORMA

L

3.4. Boolean literals

PL/SQL provides two literals to represent Boolean values: TRUE and FALSE. These values are not

strings; you should not put quotes around them. Use Boolean literals to assign values to Boolean

variables, as in:

DECLARE

enough_money BOOLEAN; -- Declare a Boolean variable

BEGIN

enough_money := FALSE; -- Assign it a value

END;

On the other hand, you do not need to refer to the literal value when checking the value of a

Boolean expression. Instead, just let that expression speak for itself, as shown in the conditional

clause of the following IF statement:

DECLARE

6

enough_money BOOLEAN;

BEGIN

IF enough_money

THEN

...

A Boolean expression, variable, or constant may also evaluate to NULL, which is neither TRUE

nor FALSE.

3.5. The Semicolon Delimiter

A PL/SQL program is made up of a series of declarations and statements. These are defined

logically, as opposed to physically. In other words, they are not terminated with the physical end of

a line of code; instead, they are terminated with a semicolon (;). In fact, a single statement is often

spread over several lines to make it more readable. The following IF statement takes up four lines

and is indented to reinforce the logic behind the statement:

IF salary < min_salary (2003)

THEN

salary := salary + salary * .25;

END IF;

There are two semicolons in this IF statement. The first semicolon indicates the end of the single

executable statement within the IF-END IF construct. The second semicolon terminates the IF

statement itself.

3.6. Comments

Inline documentation, otherwise known as comments , is an important element of a good program.

While there are many ways to make your PL/SQL program self-documenting through good naming

practices and modularization, such techniques are seldom enough by themselves to communicate a

thorough understanding of a complex program.

PL/SQL offers two different styles for comments : single and multi-line block comments.

The single-line comment is initiated with two hyphens ( -- ), which cannot be separated by a space

or any other characters. All text after the double hyphen to the end of the physical line is considered

commentary and is ignored by the compiler. If the double hyphen appears at the beginning of the

line, the whole line is a comment.

In the following IF statement, I use a single-line comment to clarify the logic of the Boolean

expression:

IF salary < min_salary (2003) -- Function returns min salary for year.

THEN

salary := salary + salary*.25;

END IF;

While single-line comments are useful for documenting brief bits of code or ignoring a line that you

do not want executed at the moment, the multi-line comment is superior for including longer blocks

of commentary.

Multiline comments start with a slash-asterisk (/*) and end with an asterisk-slash (*/). PL/SQL

considers all characters found between these two sequences of symbols to be part of the comment,

and they are ignored by the compiler.

The following example of multi-line comments shows a header section for a procedure. I use the

vertical bars in the left margin so that, as the eye moves down the left edge of the program, it can

easily pick out the chunks of comments:

7

PROCEDURE calc_revenue (company_id IN NUMBER)

/*

| Program: calc_revenue

| Author: Steven Feuerstein

*/

IS