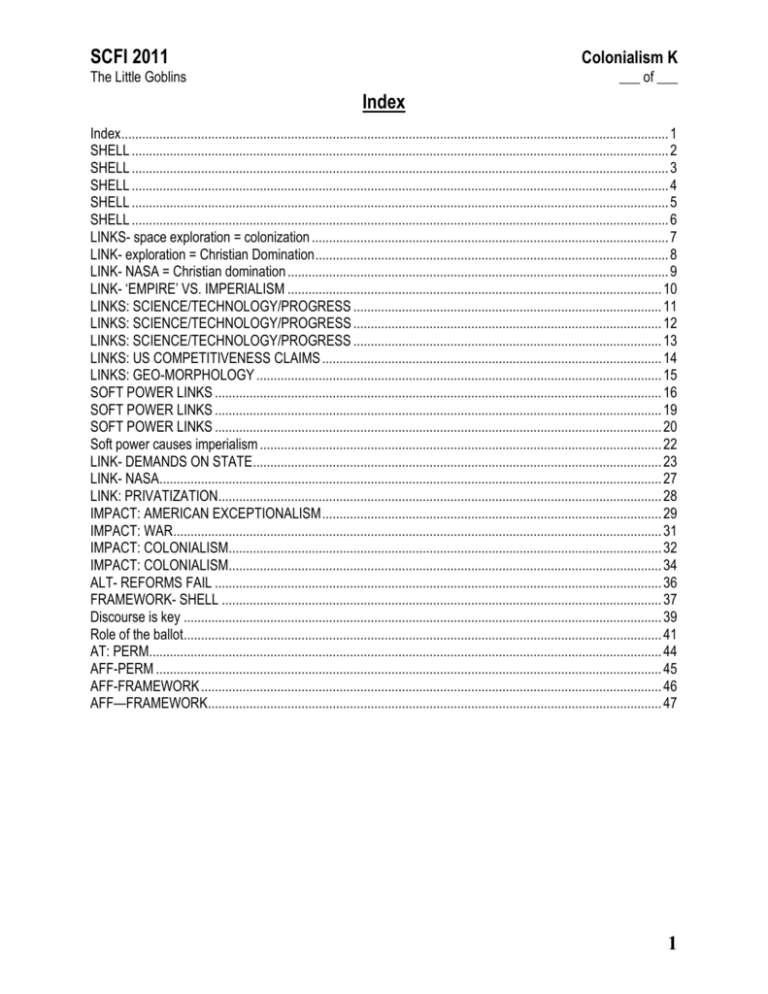

Colonialism K

advertisement