Harolds Stores, Inc. v. Dillard Department Stores, 82 F.3d 1533 (10th

advertisement

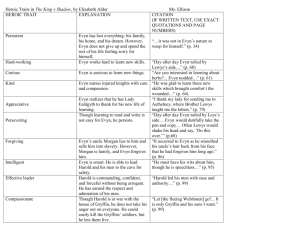

Damages, Part I Cases: Harolds Stores, Inc. v. Dillard Department Stores, 82 F.3d 1533 (10th Cir. 1996) Cimino v. Raymark Industries, Inc. 751 F.Supp. 649 (E.D.Tex.1990), rev’d, 151 F.3d 297 (5th Cir. 1998) Harold’s v. Dillard’s Facts: Harold’s alleged that Dillard’s had infringed Harold’s copyrighted fabric designs, violating federal and Oklahoman law. Specifically, Harold’s alleged that from May 1993 to August 1993, Dillard’s sold a number of skirts that appeared identical to original print skirts that Harold’s had developed and sold during the 1991-1992 season. *Harold’s had sold the skirts at issue for $78 to $80 apiece; Dillard’s priced the ‘copycat’ skirts at $28 to $30. *Two weeks after Harold’s filed its original complaint in Oklahoma (on July 7th, 1993), Dillard’s reduced the price of the skirts to $12 or $12.25, a 59% markdown that set the price at below cost. *On August 17th, 1993, Dillard’s agreed to stop selling the print skirts in markets where Harold’s and Dillard’s competed. *During discovery, Harold’s learned that a Dillard’s merchandise manager had instructed their suppliers to manufacture skirts using Harold’s skirts as “inspiration.” Another manager purchased Harold’s skirts so that Dillard’s supplier could copy the print fabric designs and styles. *Designers in the fashion industry commonly use other manufacturer’s garments for inspiration. However, industry practice requires that the derivative designs be sufficiently different to avoid copyright infringement. *Prior to trial, Dillard’s stipulated that it had infringed 19 of Harold’s copyrighted print fabrics. Dillard’s had offered 22,000 infringing garments for sale and had placed advance orders for 15,000 more, for a total of 37,000. *As Harold’s had only sold the skirts at issue during the 1991-92 season, they stipulated that Dillard’s 1993 copyright infringement did not deprive Harold’s of any sales of the copyrighted skirts. Instead, Harold’s claimed that Dillard’s acts injured its reputation and goodwill, and damaged its relations and future sales with present and prospective customers. But how to prove damages? Enter… the unsinkable Dr. Daniel Howard! (of Kis v. Foto Fantasy fame.) Demonstrating Damages: Dr. Howard’s “Shopping Survey” To establish its damages, Harold’s relied on Dr. Howard, who conducted a survey of college-age women who had visited a Dillard’s store during the relevant time (May – August 1993) and who had visited a Harold’s store or examined a Harold’s catalog in 1991 – 1992. From the results, Dr. Howard calculated Harold’s nationwide damages due to the copyright infringement. Dillard’s objected to the survey because: (1) it failed to survey a relevant universe of consumers, and (2) it was not material or probative to establish copyright damages. Applicable Rules and Standards of Review Survey evidence is admissible if it is “material, more probative on the issue than other evidence and if it has guarantees of trustworthiness.” “The survey should sample an adequate or proper universe of respondents” and should be excluded “when the sample is clearly not representative of the universe it is intended to reflect.” The district court’s admission of a survey is reviewed for “an abuse of discretion.” Dr. Harold’s Survey Instrument Instructions: Please respond to the following questions by placing a "x" in the space that most closely reflects your memories and your feelings about the issues addressed. (1) Have you visited a Harold's store or looked at a Harold's catalog in the past two years (in 1991 or 1992)? ___yes ___no ___unsure (2) Did you visit a Dillard's department store from May to August of this year (1993)? ___yes ___no ___unsure CONTINUE THE SURVEY ONLY IF YOU ANSWERED "YES" TO #1 AND #2 (3) On any of your recent visits to Dillard's, have you seen any print skirts with patterns you thought of as being unique to Harold's? ___yes ___no ___unsure (4) On any of your recent visits to Dillard's, have you seen any women's purses with designs you thought of as being unique to Harold's? ___yes ___no ___unsure (5) How likely or unlikely is it that you will purchase clothes from Harold's within the next year? very likely ___:___:___:___:___:___:___ very unlikely (6) Is this the first time you have answered these questions? ___yes ___no ___unsure The Survey – Sampling Frame Dr. Howard sampled undergraduate women from Southern Methodist University (SMU) in Dallas, Texas. A total of 1,231 surveys were collected, representing 44.3% of the undergraduate female population. 27 individuals indicated they had answered the questions previously, leaving 1,204 surveys. 578 respondents answered yes to questions 1 and 2, placing them in the relevant sample universe. 2 of these were eliminated for failing to complete the survey, leaving a final sample of 576. No incentives were offered for participation. Dr. Harold on Appropriateness of Sample “This analyst sees no reason to expect the responses of women in Oklahoma to systematically vary from those in Dallas Texas.” “Undergraduate women were utilized for study purposes since they are an important market segment for both Harold’s stores and Dillard’s.” Survey Sample – Critique Strengths -Large Sample size -Sample generally related to Harold’s core customer base (at least according to testimony) Weaknesses -Geographic variation (Dallas v. Oklahoma v. Nation) -Possible anomalies related to the Dillard’s/Harold’s serving SMU campus (Highland Park Village v. Northpark Mall) -Undergrads only -Women only -SMU only Survey Sample - Suggestions Stratification and (if necessary) weighting of sample to reflect the full proportions of Harold’s clientele Greater recognition of relevant sample variables (income, age, sex, education, etc.) If fiscally possible, cluster sampling of varying geographic locations would better support an inference concerning Harold’s national injury. The Survey Instrument – Measurement and Methodology Questions 1 and 2 – establishing a relevant sample of respondents potentially exposed to Harold’s skirts and Dillard’s copycat skirts. Question 3 – Identifying respondents who had seen skirts at Dillard’s with patterns they believed unique to Harolds. Question 4 – “purse” question – asked to eliminate “yes-saying bias” and other error. Question 5 – Scale to determine likelihood of buying from Harold’s – meant to measure the influence of the Dillard’s skirts on future purchase behavior. Question 6 – To eliminate repeat players. Measurement & Method – A critique Questions 1 and 2: Visiting is not equal to shopping/purchasing Question 3: Insufficient to indicate exposure to the skirts at issue. -A search for ‘skirts’ Harold’s website today brings up 56 hits; on Dillard’s website, 583. Question 4: A “purse” differs from a “skirt” in important ways, making it a less effective means of eliminating unreliable respondents. Question 5: This “Likert-type” question allows for relative intentions of the skirt ‘exposed’ and ‘non-exposed’ groups. However, the use of this single question allows for errors often found in “natural” experiments and “static-group comparisons.” Sources of internal invalidity: *Testing – Might their answer to this question change after being reminded of Harold’s non-uniqueness in question 3? *Selection Bias – Is exposure really the only difference between the two groups? Other Concerns: *Construct Validity – Does the answer to question 5 really tell you about the effect the “copycat” skirts had on the respondents? Measure/Method - Suggestions Ask if the respondent has shopped or bought clothing from Harold’s before. For those who said “yes” to question 3, once they’ve completed the rest of the questions ask them to identify the skirt(s) they were exposed to from a photo array of infringing/noninfringing skirts. Use “pants” or “tops” rather than “purses” for question 4. Have respondents answer question 5 first to avoid testing invalidity problems. Test reliability by delivering the survey again at another location. Include questions more specific to the connection between exposure to the copycat skirts and a decreased likelihood to shop at Harold’s: -Is any hesitation over shopping at Harold’s due to price? Quality of clothing? Style? -Has their inclination to shop at Harold’s increased, decreased or stayed the same over the past 6 months? Two years? -Could possibly include open ended questions (similar to those in the Jay report from Napster) asking why a respondent may be reluctant to shop at Harold’s – the results may not be particularly probative but may provide a source of external validation. Survey – Results Purses Yes No Unsure Row Total Yes 48 (8.3%) 66 (11.5%) 46 (8.0%) 160 (27.8%) No 12 (2.1%) 141 (24.5%) 37 (8.0%) 190 (33.0%) Unsure 20 (3.5%) 27 (4.7%) 179 (31.1%) 226 (39.2%) Column Total 80 (13.9%) 234 (40.6%) 262 (45.5%) 576 (100%) Skirts (X2 = 235.01; p < 0.00001) Mean Scores on Intentions to Purchase Clothes from Harold’s within the Next Year Purses Skirts Yes No Unsure Yes 5.60 N = 48 3.18 N = 66 5.17 N = 46 No 3.92 N = 12 4.75 N = 141 4.97 N = 37 Unsure 4.90 N = 20 4.26 N = 27 4.44 N = 179 Conclusions – Damage Calculation The survey showed 27.8% (N = 160) of respondents identifying Dillard’s skirts as having patterns unique to Harold’s. Of these, 8.3% said “yes” to purses and 8.0% said “unsure” to purses. Eliminating these leaves 11.5% (N = 66). For those who did not see unique skirts nor purpose, their mean likelihood to shop at Harold’s was 4.75. For those who saw the unique skirts but did not see the purses, their mean was 3.18. The difference between these means is 1.57, or 33.1%. Thus, Dr. Howard found the skirts lead to a 33.1% reduction in a respondent's intention to visit Harolds. Drawing on several trade journals, Dr. Howard extrapolates a .341 multiplier to estimate the likely relationship between the decrease in purchase intent and a decrease in purchase behavior. He concludes that the actual reduction in purchasing behavior will be slightly more than 11 percent. (0.331 x 0.341 = 0.113) Damage Calculation - Continued From there, Dr. Howard basically utilizes a series of attenuated assumptions to calculate damages. For example, *Based on a national study that reported 55% of men’s apparel was bought by women, the same proportion was assumed for Harold’s. *The survey above shows that 44% of men’s apparel nationally is purchased by men. Based on a telephone survey of 100 SMU males, Dr. Howard found that 48.6% of a man’s expenditures on men’s clothing was influenced by advice from women. Thus, an additional 21.4% (.486 x .44) of men’s apparel purchases nationally (and presumably in Harold’s) are influenced by women. *Thus, 76.4% (55.0% + 21.4%) of men’s clothing at Harold’s is potentially affected by Dillard’s skirt copying. Wrap-up The Court finds that the shopping survey was properly admitted. It concludes that “there was substantial evidence tending to support the jury’s damage award” of $312,000.00. Do you agree? Cimino v. Raymark Industries “I view your role as one of the commanding generals. You are the Eisenhower of this D-Day operation. The rest of us are colonels prepared to take orders in this joint effort… The magnitude of this assignment is unprecedented in federal court history…” -Judge Robert Parker, who presided over Cimino in the Eastern District of Texas, encouraging Judge Charles R. Weiner of the Eastern District of Pennsylvania. Two days earlier, the full asbestos caseloads of eight federal district judges had been transferred to Weiner’s court in a mass consolidation effort. “Many Mistakes and Missed Opportunities” The Asbestos Crisis Leading up to Cimino 1981: Forty-Eight Insulations seeks discovery to help establish a district wide market share determination among the defendants. -Forty-Eight Insulations abandoned its motion under pressure from its co-defendants. The Texas district court failed to press the issue. 1981: The district court used issue preclusion to declare asbestos containing products unreasonably dangerous as a matter of law, and further precluded plaintiffs from seeking punitive damages. -In Hardy v. Johns-Manville Sales Corp., 681 th F.2d 334 (5 Cir. 1982) the Court of Appeals rejected the approach. Mid-80s: The district court established a voluntary ADR program. Most defendants elected to participate and a number of settlements ensued. -The ADR program was set aside by the Eastern District Sitting en banc. 1986: In Jenkins v. Raymark Industries, Inc., 782 F.2d 468 (5th Cir. 1986), the 5th Circuit approved of Judge Parker’s certification of a class of 900 asbestos claimants for certain common questions. -After that order and certain settlements, 3,031 asbestos personal injury cases accumulated in the Eastern District of Texas. 1989: Judge Parker attempts to consolidate the 2,990 Cimino class members into a single group, represented the full trials of the 11 class representatives plus 30 “illustrative” cases – 15 chosen by the defendant and 15 by the plaintiff. -The plan was rejected by the Court of Appeals in In re Fibreboard Corp., 893 F.2d 706 (5th Cir. 1990). As a result of delays and difficulties, as of 1990: *448 class member died waiting for their cases to be heard *$.61 of every asbestos-litigation dollar went to transaction costs. *Raymark, Forty-Eight Insulations, Unarco, Standard Asbestos, Johns-Manville, Eagle Picker, and Celotex were bankrupt. *Federal asbestos filings averaged 1,140 per month. *For every case resolved, two new ones were filed. Judge Parker notes in the introduction of Cimino, “If the court could somehow close thirty cases a month, it would take six and one-half years to try these cases and there would be pending over 5,000 untouched cases at the present rate of filing.” So Why do you Care? When analyzing Judge Parker’s trial plan for Cimino, it pays to keep the asbestos context in mind. As Saks & Blank note in Justice Improved, when responding to the objection that aggregation denies parties procedural justice, one answer comes from asking the question, “Compared to what?” Cimino v. Raymark – The Plan The class consisted of 2,298 plaintiffs claiming asbestosrelated injury or disease resulting from exposure to defendants’ asbestos-containing insulation products. These plaintiffs went to trial against Pittsburgh-Corning, Fibreboard, Celotex, CareyCanada, and ACL. The trial plan consisted of three phases: Phase I: A complete jury trial of the entire cases for the nine class representatives and a class-wide determination of issues of product defectiveness, warning, state of the art defense and fiber type defense. The jury also assessed a punitive damages multiplier for each defendant “for each $1.00 of actual damages” as follows: Carey-Canada…..$1.50 Fibreboard……….$1.50 Celotex……………...$2.00 Pittsburgh-Corning...$3.00 These procedures were approved of in Jenkins by the Court of Appeals. ACL was granted a nonjury trial pursuant to the foreign sovereign immunities act. Phase II: This phase required a jury finding for each of the worksites, crafts, and relevant time periods as to whether asbestos-containing insulation products were used, as well as which groups were sufficiently exposed to such asbestos products to cause the alleged injuries. Finally, an apportionment of causation was made among defendants, settling and non-settling. In the actual trial, Phase II was dispensed with on the basis of a stipulation amongst the parties. (On appeal, the 5th Circuit found the trial plan violated defendants’ Seventh Amendment rights. They noted that “under Texas law causation must be determined as to ‘individuals, not groups.’ And, the Seventh Amendment gives the right to a jury trial to make that determination.” The Court based this result on the Erie doctrine – requiring Texas substantive law to apply -and Congress’ failure to act. On the other hand, in his concurrence Judge Garza suggested that “Judge Parker’s phase II plan would have been sufficient if he had implemented the plan rather than disposing of it with the phase II stipulation.”) Phase III: DAMAGES All Cimino plaintiffs waived their right to an individualized verdict and agreed to the Phase III procedure. The 2,298 class members were stratified into five disease categories based on the plaintiffs’ injury claims. A random sample was selected from each category as follows: Sample Size Disease Category Population Mesothelioma 15 32 Lung Cancer 25 186 Other Cancer 20 58 Asbestosis 50 1050 Pleural Disease 50 972 TOTALS 160 2298 Calculation of Damages: *Two juries were utilized to hear the randomly selected 160 sample cases. Each plaintiff selected was awarded his individual verdict. Afterwards, the non-sample plaintiffs were each awarded the average verdict of all the samples within their disease category. *The defendants were not allowed to present evidence on causation but were permitted to present evidence of contributory evidence, such as smoking. *The Court ordered remittiturs in thirty-four of the pulmonary and pleural cases and in one mesothelioma case.*** *Zero verdicts were also factored into the damages awarded to nonsample plaintiffs. ***Note: Pleural Disease is the least serious of the disease classifications; yet the average pleural disease award exceeded that of asbestosis and lung cancer by more than $10,000, even with the remittiturs and zero verdicts. Phase III – Statistical Analysis The defendants argued that aggregate valuation was inappropriate for mass tort cases. Judge Parker responded first by pointing out the defendants’ hypocrisy, given their own reliance on statistics during the trial. In support of his use of statistics, Judge Parker quotes the 6th Circuit Court of Appeals in E.K. Hardison Seed Co. v. Jones, 149 F.2d 252, 256 (6th Cir. 1945), “The prerequisites necessary to the admission in evidence of samples are that the mass should be substantially uniform with reference to the quality in question and that the sample portion should be of such nature as to be fairly representative. The 99% Confidence Interval After the 160 verdicts were rendered, Judge Parker held a post-trial hearing to evaluate the representativeness of the sample cases. The Court sought a confidence level of 95% (+/- 2 standard deviations). The plaintiff’s statistical expert, Dr. Frankiewicz, examined the “goodness-of-fit” between the samples and the disease categories, considering a range of variables relevant to causation and the category population. Dr. Frankiewicz determined that, with two minor exceptions, the samples on a whole achieved a 99% confidence level, or a standard deviation of +/- 2.56. The Court declared that the actual precision level of the samples “exceed[ed] that sought by the Court.” How confident are you in this analysis? Confidence Level v. Interval “All statements of accuracy in sampling must specify both a confidence level and a confidence interval.” -Course materials, Chapter 7, “The Logic of Sampling,” p. 204. For example, a Gallup poll may tell us, “One can say with 95% confidence that the margin of sampling error is ±3 percentage points.” This means that 19 times out of 20 (confidence level), the poll will be within 3 percentage points of the actual public opinion (confidence interval). Cimino gives us the confidence level while failing to specify the confidence interval – a wide confidence range (like a range of +/- 25 percentage points in a poll) could lead one to doubt how representative the sample cases really are. Still, given the number of samples taken of each disease category, if the population resembles a normal bell curve the standard deviation from the mean is unlikely to be large… though it may still be significant. Hypothetical Standard Errors Hypothetical Standard Error* based on Gender** Hypothetical Standard Error* based on Worksite*** Sample Size Disease Category Population Mesothelioma 15 32 6.85% 3.06% Lung Cancer 25 186 8.66% 3.87% Other Cancer 20 58 7.33% 3.27% Asbestosis 50 1050 6.73% 3.01% Pleural Disease 50 972 6.71% 3.00% TOTAL 160 2298 *Standard Error = square root of (product of population parameters [P x Q] divided by sample size [n]). As each sample size is around 5% or more of the actual population, we must multiply the error rate above by a "finite populational correction" (1 - proportion of population) to achieve the true standard error. **Presuming 50% of population of Plaintiffs is female. (Note: This was likely not the case in Cimino.) ***Assuming that each of the 19 worksites was represented in equal proportion by the plaintiff population -- in other words, that 5.26% of the plaintiffs came from any one worksite. (Note: This was likely not the case in Cimino. Aggregating Well: Tips from Saks and Blanck Representativeness is the touchstone of good sampling. *When measuring the representativeness of your sample, set your p-level high. -Conventional significance testing (with plevels of .01 or .05) aims to be conservative about erroneous rejection of the null hypothesis, i.e., making it hard to find a significant difference. -In sampling from known aggregations, the reverse is true: we want to guard against erroneously concluding that the sample equals the population mean. Thus, we want to make it easier to reject the null hypothesis. This can be done by setting the p-level for the proposed significance tests at .20 or higher. *Remember that representative samples may become less so over time (for ex., as plaintiffs die off or are added.) *Draw enough samples to satisfy legal standards. Achieve within-group Homogeneity and BetweenGroup Heterogeneity *Stratify: Using the 5 disease groups in Cimino helped ensure adequate representation of each group and created more homogenous subpopulations. *Use data from past jury awards to determine which variables were important -- these can be used to form subgroups *Using cluster analysis on data describing the case population can help to maximize between-group heterogeneity and within-group homogeneity. Due Process – the Legal Standard Perhaps the greatest hurdle faced by aggregative sampling is legal xenophobia – as in the strict adherence to a “traditional” form of due process. Principles of Due Process are embodied by the Matthews Test, as well as instrumental and noninstrumental values. Due Process – Matthews Test In Matthews v. Eldridge, the Supreme Court identified 3 factors that shape the due process balancing test: (1) The private interest of the defendant affected, (2) The risk of erroneous deprivation of interest through the procedures used, and (3) The Government’s interest, including all fiscal and administrative burdens that the additional procedure would require. *In suits involving private parties, the Court in Connecticut v. Doher modified the third prong to focus on the private interest of the plaintiff, with the Government’s interest as an ancillary concern. Matthews Test – Applied to Cimino (1) Defendants face a minimal reduction in control and in appearance of due process; they will likely pay about the same damages while saving significant transaction costs. (2) For the defendants, little risk of erroneous deprivation. (3) The plaintiffs may face the prospect of having no recovery, being forced to settle or dying before their case comes to judgment. Government has a strong interest in streamlining the asbestoslitigation process. Due Process – Noninstrumental Values “Appearance” of Justice Equality before the Law Predictability Transparency Rationality Participation Revelation Aggregation and Noninstrumental Values Saks and Blanck suggest that nearly all noninstrumental values are equally, if not better supported by the aggregation procedure. The one possible exception is that of the “appearance” of justice – that aggregation denies procedural justice. In response, Saks and Blanck point out that Aggregation has never been compared empirically with traditional procedures. While aggregation may give defendants more limited process, it won’t shut them out of trial opportunities altogether. In contrast, a plaintiff’s only real shot at having their day in court may be vicariously through aggregation and sampling. Thus, aggregation may afford the most procedural justice under the circumstances. Due Process – Instrumental Values The major instrumental value is *Accuracy – the right to notice, hearing, and counsel each contribute to a more accurate process. A fair process ought to result in plaintiffs receiving, within reasonable tolerances, the proper amount in damages. The process should lead to rational, reasonably accurate, and nonarbitrary outcomes. Aggregation – A stronger path to Instrumental Accuracy Utilizing an array of damage awards, the ‘aggregate’ award is more likely to come near the ‘true’ or ‘correct’ damage measure than a single verdict. Aggregation will refine out some of the random and systematic error (ex. Irrationality and bias) of jury decisions, while preserving the core of the jury’s logic. Accuracy is unlikely to be a problem for defendants with any reasonably done aggregation procedure. Seventh Amendment - Juries Given the disparity between the two juries in the Cimino case, a larger number of juries may be preferable. Still, like any other sample, we need not use a jury for every single case to achieve reliability. When using multiple juries, the cases should be assigned randomly. A quick note on Plaintiffs v. Defendants Interestingly, though the defendants were the ones to protest in the Cimino case, aggregate procedure is much more likely to award an inappropriate amount to a plaintiff than to charge an inappropriate amount to a defendant. Ex. In Cimino, nonsample plaintiffs who did not smoke still had their awards reduced by any contributory negligence found against a sample plaintiff who smoked. This anti-plaintiff bias leads some to suggest that while it is reasonable to mandate that defendants submit to aggregate procedure, it is not reasonable to force plaintiffs to do so, unless the risks can somehow be shifted to the defendant. Alternative I – Abraham/Robinson Aggregative Valuation In “Collective Justice in Tort Law,” Profs. Abraham and Robinson propose compiling a statistical model for determining individual claims: Baseline appraisals of the value of individual claims would be set by using statistical claim profiles, or models. The profiles would indicate the amounts paid in judgment or settlement to claimants falling into different categories. These categories would be defined as functions of variables that affect liability and the severity or duration of plaintiff’s illness. Claim valuation would be a function of probability and magnitude of payout. Thus, the estimated parameters could be used to calculate damage awards for untried cases. Alternative II - the “Plaintiffs Cut, Defendant Chooses” Model Seeking to deal with aggregation’s tendency to place the full burden of precision on plaintiffs, David Friedman has hypothesized an “Incentive-Compatible” Procedure for litigating mass torts: (1) Attorney for N plaintiffs produces, for each plaintiff i, a claim C[i], which is the amount the attorney claims that plaintiff i aught to receive in damages. (2) Plaintiff gives list of claims C[i] to defendant’s attorney. (3) Defendant’s attorney selects a small number (say, 10) of cases to be tried. (We’ll call these plaintiffs 1-10.) (4) These cases are tried. The court awards damages D[i] to each of the 10 plaintiffs. (5) The court calculates R = (D[1]/C[1] + D[2]/C[2] +…+ D[10]/C[10])/10, and awards damages of R x C[i] to each of the N plaintiffs. Under this system, the plaintiffs’ attorney will have incentive to make each claim reasonably proportional to actual damages. (Do you see why?) Friedman suggests several variations on this model to control for cost and errors.