Treatment (2)

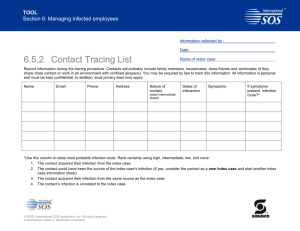

advertisement