Modernism in Home to Harlem and Song of the Towers

advertisement

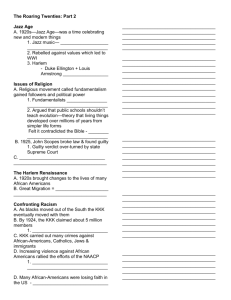

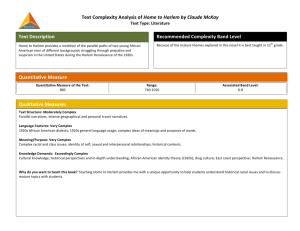

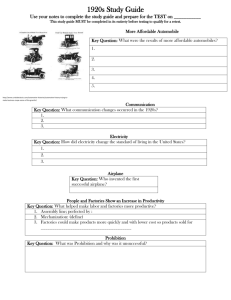

Modernism in Home to Harlem and Song of the Towers Modernism in Home to Harlem and Song of the Towers: A Collaboration of the Visual and Literary Art Forms Karyn L. Hixson Texas Woman’s University May 7, 2012 1 Modernism in Home to Harlem and Song of the Towers 2 During the years 1914-1939 many artists, painters, and designers of the Harlem Renaissance passionately committed themselves to the ideas which we now call Modernism. The term modernism has something of the character of a provincial life (Baker 84). Promising an intended and uncompromising break with traditional values, life and all things being relative, the experience with alienation, loss and despair, and the need to champion the individual and celebrate inner strength (Cooper 297-306; Davis 95-6; Baker 87). I maintain Claude McKay and Aaron Douglas’ works emphasized a strong intentional break with tradition, because the aim of both artists was to make Americans uncomfortable with a depiction of how life really was for black people during the Harlem Renaissance. Furthermore, the story Home to Harlem and the illustration ”Song of the Towers” represent a realistic description of Harlem and the life African Americans experienced during the Harlem Renaissance. Some scholars disagree. Nathan Huggins charges that the Harlem Renaissance movement failed because the artists and spokespeople didn't realize that they did not have to battle for a defining identity in America. They only needed only to claim their nativity as American citizens (Baker 89). My paper theorizes the relationship between artistic representation and the ideas modernism engendered made a significant impact to uplift the African American or more commonly called “The New Negro”. Modernism and the Harlem Renaissance The best of humanity's recorded history is a creative balance between horrors endured and victories achieved, and so it was during the Harlem Renaissance.” ― Aberjhani The Harlem Renaissance recorded tragedy indeed, but it also was the outlet for many African American artists, painters, musicians, poets and many others. Reacting to the Modernism in Home to Harlem and Song of the Towers 3 extraordinary violence and destruction of World War I, African American artists searched for ways to create a better world through art and design (Cooper 297). Many architects, designers, and artists of all genres passionately committed themselves to the ideas which we call modernism. For my essay, I am speaking of modernism in terms of change that occurred in African Americans during the Harlem Renaissance. It includes literature, music, art, graphic design, and intellectual history. It is not confined to tradition, because during the Harlem Renaissance attitude and convention were challenged. Modernism implies chronology and that can make modernism’s movement unending (Baker 85). The modernist movement during the 1920’s in New York’s Harlem focused on a descriptive catalogue of works that used many collaborative efforts between artists. Literature and art are two genres that typically partnered with one another. Music and dance was another well known convention. In these cabinets of discontinuous objects, space is shared because that is the very function of the cabinet – to house similar works that concentrate on similar themes (Baker 85). That theme is modernism. In Douglas’ “Song of the Towers” you can see his creativity in his illustration. He had a unique style, something that all of the artists of the 1920s had begun to express in their own unique way. The freedom that was afforded the “New Negro” by W.E.B. Du Bois and the rest of the talented 10th was making its mark. This freedom was expressed in literary and artistic scholarship which was shared in comprehensive accounts in modern writings and art of the times (Baker 85). This change is more accurately defined as awareness in the mind of the “New Negro” and no one (not even those involved) could chart the outcomes of this new revelation. Modernism in Home to Harlem and Song of the Towers 4 With the new proclamation of independence and strength, the movement did have fragments and there were disagreements. The uncharted waters were taken seriously, and with sincerity, leaders of the movement forged ahead to continue the fight for change. Claude McKay throughout the twenties remained the “aesthetic radical” (Cooper 302). He affirmed the value of his non-social personality and considered himself the “natural man”, willing to be only himself in an age of conformity and change (Cooper 302). This was certainly evident in his writings. Claude McKay and Aaron Douglas’s contribution Claude McKay was born in September 15, 1889 on the British West Indian island of Jamaica. In 1912, at the age of 23, McKay came to the United States to study agriculture at Tuskegee Institute. In Jamaica, McKay had already established a reputation as a poet, having produced two volumes before leaving his homeland; Song of Jamaica and the Constab Ballads (Cooper 298). The Song of Jamaica was his first written book and it was written in patois (patwah), a native dialect. The Constab Ballads was based on his very short stint with the Jamaica Constabulary Force. McKay came to the United States eager and hopeful for a bright future. His initiation into the realities of the Negro life was recorded in Pearson’s Magazine: “It was the first time I had ever come face to face with such manifest, implacable hate of my race, and my feelings were indescribable…..Then I found myself hating in return (Cooper 299). McKay like so many others, who came to New York looking for the American dream, found that it wasn’t available to them (African Americans). As his experiences in the States continued to harden his attitude, McKay’s writing style changed as well. His very famous poem appeared in the July 1919 issue of the Liberator, “If We Must Die”. Some critics have argued that this poem depicts a Modernism in Home to Harlem and Song of the Towers 5 desperate show of defiance and seemed a statement of tragic hopelessness (Cooper 301). The modernist’s view of the poem resonates an inner strength. He used the phrase “if we must die” several times in the poem. This indicates he doesn’t want to die a horrible death and if death is near, unrestrained action must be taken. This attitude McKay displays in his poem is indicative of the modernist theme. His intended break from the traditional and how he builds on his inner strength; forces the American public to feel uncomfortable as they view through his literary lens the aspects of Negro life in America. In McKay’s most famous novel Home to Harlem the modernist theme continues. McKay looks among the common people for a distinctive black identity. As McKay developed as a poet and a writer, “his strongest attribute was the extreme dislike for prevailing standards of racial discrimination: hence he lost no opportunity, when writing to attack the status quo” (Smith 270). McKay’s characters Jake, Zeddy and Ray articulate the tensions he lived with and strived to reconcile as an artist (Williams 101). The structure of Home to Harlem is sequential. Its foundation takes a journey as Jake’s continuous pursuit of home unveils. Modernism promises a relentless break with traditional values. A long established way of thinking in America is to have contempt for foreigners: “Jake was very American in spirit and shared a little of that comfortable Yankee contempt for poor foreigners. And as an American Negro he looked askew at foreign niggers” (Andrews 157). In Chapter X titled “The Railroad” McKay examines this contempt as Jake and Ray meet at the railroad job Jake had just taken to get away from Harlem. Jake had just broken up with Rose, so he was broke. After work, he watched the other waiters play poker. One waiter sat alone reading. Jake asked him for a loan two dollars, he got it, played, won five Modernism in Home to Harlem and Song of the Towers 6 dollars, repaid the loan – a friendship began. Jake soon found out that Ray was from Haiti and spoke French. Ray gave Jake a lesson about his country, their revolution, and he spoke about the leader of the black slaves Toussaint L’Ouverture. It was the first time Jake had heard such fascinating stories. “The waiter told him that Africa was not jungle as he dreamed of it, nor slavery the peculiar role of black folk. The Jews were the slaves of the Egyptians, the Greeks made slaves of their conquered, the Gauls and Saxons were slaves of the Romans” (Williams 157-58). This revelation gave Jake new pride. He discovered that Ray was a learned man, but they still had many of the same challenges because of their race. This friendship is paralleled with the breaking of the intentional contempt for foreigners that McKay’s modernist view allowed. Life and all things being relative, functions as a comparative thread for modernism and the Harlem Renaissance. Life is dependent upon external conditions or forces that gage and influence decisions we make. In Chapter I – “Going Back Home” of McKay’s Home to Harlem, the story begins with Jake living in a bad environment: “the freighter on which he stoked was that it stank between sea and sky” (Andrews 105). He was working with a dirty Arab crew only because one of them had quit. The dinghy was filthy. The white sailors who washed the ship wouldn’t wash the stoker’s bathroom because they disliked the Arabs. The cook placed the stoker’s meal in three pans, the stoker who carried the meal back to the bunks stacked the pans one inside the other and the bottoms of the pans were sometimes dirty. Arabs touched the meat with their unwashed, coal-powered fingers: “Jake was used to the lowest and hardest sort of life, but even his leather-lined stomach could not endure the Arabs’ way of eating” (Andrews 105). Modernism in Home to Harlem and Song of the Towers 7 Jake remedied his eating situation by paying the chef a ten-shilling note, “and the chef gave him his eats separately” (Andrews 105). This scene captures the essence of external conditions influencing decisions we make. Jake was in an unbearable situation. Why did he endure? He could have left like the first guy did. In his mind he was thinking about the outcome: “Jest take me ‘long to Harlem is all I pray” (Andrews 106). Jake’s predicament is equivalent to the plight of the southerners who migrated north. They too were living in intolerable living conditions, mistreated in their communities, and most times fearing for their lives. The decision to move north came from years of torture and exploitation, forcing them into uprooting themselves to come north in search of a better life. Jake’s decision to come home was consistent with the southern man to migrate north. McKay’s point of view certainly underscores the modernist’s perspective. Situations cause and definitely influence the decisions we make. Jake’s longing for home was greater than what he had to endure to get there. The situation was similar to the people who migrated north. Their living conditions prompted the search for something better. This motif of searching for something better, a home in this case, shows how McKay from the beginning of the novel expressed how the aspects of Negro life were not as comfortable as life for other Americans. This modernism theme continues in Chapter II, named appropriately “Arrival”. Jake Brown’s arrival in Harlem can be summed up in twelve points that again share with the world McKay’s modernist, but realistic view of how life really was for African Americans. This assessment shows the thinking process the average Harlem Renaissance African American man. One, Jake arrives with his pay, fifty-nine dollars. Second, the first thing he does is get a drink: Modernism in Home to Harlem and Song of the Towers 8 “Jake drank three Martini cocktails with cherries in them” (Andrews 108). Third, he gets a fried chicken dinner, a big one. It’s so big the book labels it “a Maryland fried-chicken feed” (108). Four, “His blood was hot” (Andrews 108). These first four items are very stereotypical of how an African American man is viewed. This is the very reason why the intellectual blacks didn’t care for the way McKay exposed vulnerabilities of the psyche of the African American man. Five, Jake goes into a cabaret, looking good in his steel-gray English suit: “She knew at once that Jake must have just landed” (Andrews 108). Jake looked just like King Solomon looked when he got off the train in New York. That naïve look, big eyed, ripe on the vine, ready to be picked. Although he initially thought he was picking her. Six, Jake comments just to make sure they are on the same page: “Is it clear sailing between us sweetie?” (Andrews 109). Seven, at this point it’s every man for himself. Jake wants intimacy and she wants money. “She was intoxicated, blinded under the overwhelming force. But nevertheless she did not forget her business” (Andrews 109). In this scenario the little brown girl begins to like Jake, but she can’t forget why she is with him. Eight, here she gets straight to her business. If he has money, she wants it or she wants out: “Daddy, I wants fifty”. Nine, it is decision time for Jake. He only had fifty-nine dollars to begin with and she wants fifty for her services. What does Jake do? “After Jake had paid for his drinks, that fifty dollar not was all he had left in the world. He gave it to the girl” (Andrews 110). It is a defining moment for Jake, the brown skin girl, and the readers of the novel. Again, the intellectual set would have liked Jake to make a better decision. At least barter her down a little. He cheerfully gives her the fifty dollars. Ten, after a wonderful and costly evening, Jake wakes up and she gives him coffee and doughnuts. Eleven, Jake walks down Modernism in Home to Harlem and Song of the Towers 9 Lenox Ave and shoves his hand into his pocket and pulled out the fifty dollars. Lastly, Jake reads a little piece of paper he finds in his pocket: “Just a little gift from a baby girl to a honey boy” (Andrews 110). This scene is very powerful. The distressing sentiments of a provincial lifestyle, characteristic of unsophisticated inhabitants engaging in a relationship that is expected, but turns conventional reveals McKay’s softer lascivious side. McKay was from a loving family back in the islands. He had family and from this episode it shows he had experienced compassion from a female somewhere in his experiences. The chapters discussed here only tip the iceberg. McKay’s Home to Harlem is filled with perspectives that give the appearance of a careless man doing foolish things and making bad decisions. In actuality, McKay tried to dispense as many schemes and directions the African American man has to deal with on a regular basis. Although, the little brown girl was a prostitute, her character as a woman with values was implicated when she gave the fifty dollars back to Jake. The modernists theme of building inner strength and celebrating the individual is shown in Chapter II. African American women were viewed as hot blooded. A prostitute with bad morals and scandalous values was a common assumption of the African American woman during the Harlem Renaissance. This portrayal of the kindness of the brown girl brought a moment of positive exhilaration for the African American female. “Aaron Douglas was born May 26, 1899, 10 years after McKay, in Topeka, Kansas. An educator, he graduated from the University of Nebraska in 1922. He taught art in Kansas City before leaving for New York” (Davis 95). “There he met Winold Reiss, a painter who motivated him to delve into the past to explore his African heritage as a source of subject matter for his Modernism in Home to Harlem and Song of the Towers 10 work” (Davis 95). There are many accounts that claim Aaron Douglas’ first major commission was a book jacket for Alain Locke’s The New Negro. An examination of the “Notes to the Illustrations Page” in the book revealed that Locke credited Reiss for his graphic interpretations of Negro life, not Douglas. Douglas’ work was considered to be the first successful attempt at breaking tradition and integrating African subjects in his paintings, murals and illustrations to show the different aspects of the African American Negro during the Harlem Renaissance (Earle 139). “Aaron Douglas’ most arresting and innovative art was created in his murals, where he was able to experiment with color, Cubism, and African art” (Kirschke 19). In Douglas’ work, especially his murals, the visual experience brings us back to our modernist themes. Looking at the paintings gives the viewer an experience with alienation, loss and despair, and the need to support and encourage the African American who is struggling with confidence and identity. This modernism was necessary during the time of the Harlem Renaissance to proclaim a pride in African heritage. Douglas was inspired by his African American heritage when he painted Rebirth. Aaron Douglas, Encyclopedia of the African American experience by Richard Powell Modernism in Home to Harlem and Song of the Towers 11 This painting uses black and white color showing strength. Douglas’ signature style shows flat, angular imagery and reflects the influence of ArtDeco and African art (Powell). Many visual artists played a key role in promoting the image of the New Negro. Douglas was best known for his mural collections. The murals in the New York Library, “interpreted the spiritual identity of black people as a kind of “soul of self” that united all black people” (Davis 96). Douglas created a type of art that was unique. It was a mix of African art he had seen and later silhouettes for his murals usually consisting of four panels telling a story. For his murals, Douglas’ style “featured semitransparent silhouettes of black people in heroic poses representing struggle and triumph, mystically overlaid by concentric, circular bands of light (Kirschke 19). A couple of paintings that show this style are Crucifixion and Into Bondage. Modernism in Home to Harlem and Song of the Towers 12 Aaron Douglas, Encyclopedia of the African American experience by Richard Powell In these illustrations the subtle hints of color, with the strong characters and items pictured in each photo, are symbolic of the life African Americans were living during the Harlem Renaissance. The “Crucifixion”, represents a cross as a symbol of Christ death. This image shows the inner strength African Americans needed to draw upon in their everyday struggle to survive. The uplifted head of the man in “Into Bondage” surrounded by palm branches gives a feeling of hope. Notice the band of light that beams through each painting. Aaron Douglas, Encyclopedia of the African American experience by Richard Powell Modernism in Home to Harlem and Song of the Towers 13 Douglas was commissioned for the Countee Cullen Branch of the New York Library to paint a mural in 1934 under the sponsorship of the works Progress Administration (Kirschke 24). It was titled “Aspects of Negro Life”. It consists of four large panels and each one conveys a different message. Douglas and McKay both became interested in Marxism, a development common among black intellectuals and artists of the 1930s (Kirschke 26). However, these politically extreme views and principles didn’t transform Douglas’ work (unlike McKay). The first panel in Douglas’ mural was The Negro in an African Setting. The motif continues our modernist theme. It emphasizes the strongly rhythmic arts of music, dance, and sculpture which have greatly influenced the modern world (Kirschke 26). The second panel Slavery through Reconstruction depicts the doubt slaves had when reading the Emancipation Proclamation. The third panel, An Idyll of the Deep South, portrays blacks in the fields on the right side, singing and dancing in the center, and mourners grieving the death of a man who has been lynched on the right (Kirschke 26). Douglas’ murals illustrate a very realistic view of how life was for African Americans during the Harlem Renaissance. The scenes of sadness, loss and despair, are woven around singing and dancing. These opposite emotions complete the story of life. In the struggles outlined in the murals, triumph is given the same amount of space, but it carries more value. The fourth panel (shown below), Song of the Towers, shows a masculine figure fleeing from the hand of servitude. This image is exactly the type of uncompromising conception of lifestyle Douglas wanted to show. It is symbolic of the migration of African American people leaving their rural southern homes to the urban industrial life of a northern “free” man (Kirschke Modernism in Home to Harlem and Song of the Towers 14 27). Standing on what looks like a wheel in the center of the composition there is a saxophonist which probably symbolizes the Harlem Renaissance movement with art being the connector between the races. Aaron Douglas, Encyclopedia of the African American experience by Richard Powell The wheel can also represent “the will” the express oneself. A figure on the left holds his head in his head as the hand of death looms over him (Kirschke 27). Through Douglas’ work he explored and challenged himself in ways that involved him with African American history and politics. Many of his painting did show the tribulation faced by Negroes during the Harlem Renaissance, but the modernist themes helped to support and protect the downtrodden. Both McKay and Douglas felt an urgent need for unity among African Americans. Through their work, they understood how to portray those emotions. Viewed as part of modernism art Modernism in Home to Harlem and Song of the Towers 15 Home to Harlem by McKay and “Song of the Towers” by Douglas, illustrate a realistic view of life as an African American during the Harlem Renaissance. The novel Home to Harlem was a success because of its emphasis and details of Harlem nightlife. Harlem was a place everyone had heard of and many wanted to experience. The novel was an attempt to take the audience into the clubs and lifestyle of different characters. Jake the protagonist who wanted nothing more but to return to Harlem: “Take me home to Harlem, Mister Ship!” (Andrews 108). Jake’s encounter with “the girl” gives the reader the kind look into the primitive sexual desires many wanted to know about. One of McKay’s critics and a writer himself, W.E.B. Du Bois didn’t care for the depictions of sexuality and the nightlife. In Home to Harlem Du Bois felt “the novel’s frank depictions of sexuality and the nightlife in Harlem only appealed to the “prurient demand(s) “ of white readers and publishers looking for portrayals of black “licentiousness” (Hunt 339). Both works of art, Home to Harlem and Song of the Towers show their creators commitment to modernist views. The characters in McKay’s novel parallel Douglas’ silhouette figures in that, the loss and despair experienced, the intentional breaks with traditional values, and feelings of alienation all come together to champion the struggle of African Americans. In the artists quest to make the public squirm when they view the uncomfortable look at life for the African American. In viewing this, it generates a more sympathetic emotion from its audience. Modernism: The Failure of the Harlem Renaissance Not everyone was in agreement about the success of the Harlem Renaissance. There were critics who accuse many of the artists promoting unification of the African Americans, as the Modernism in Home to Harlem and Song of the Towers 16 cause of discontentment. In a review published by I. De A. R., Claude McKay was blasted for not realizing that his portrayal of African American life in his novel Home to Harlem; “where the individual becomes a problem to himself and to society” (I. De A. R. 96), actually hurt the reputation of the people he was trying to uplift. I disagree, McKay’s sensual and sometimes brutal accuracy gave the literary world a jolt and it was greatly impacted by his novel Home to Harlem. His characterizations of Jake, and Zeddy who go down different paths, showing how two black men struggle through life trying to find their way, as they deal with the prejudice in American society. There are many other scholars who are far from exuberant in their assessment of the Harlem Renaissance. In an article on Modernism and the Harlem Renaissance published in the American Quarterly, a Harvard historian Nathan Huggins did a provocative study on the Harlem Renaissance. He asserts that many of the spokespeople for the Harlem Renaissance accepted the province of “race” as a domain in which to forge a New Negro identity (Baker 89). He mentions Countee Cullen, Claude McKay, Langston Hughes, Alain Locke and others who he felt battled for an identity already present for African Americans. “In fact, he holds that they are nothing other than “Americans” whose darker pigmentation has been appropriated as a liberating mask by their lighter complexioned fellow citizens” (Baker 91). The Harlem Renaissance was a collaborative effort between many artists; representing all genres. Participation in the movement forged many alliances, some of them merging with the efforts of already established political organizations (Marxism, Communism). A few factions appeared, allowing an exclusive few into membership (the talented tenth). Informal friendships Modernism in Home to Harlem and Song of the Towers 17 formed into valuable associations to construct an outlet for the creative African Americans who bore a natural proclivity to express themselves through their respective art forms. They revealed themselves, their feelings, their tragedies and their successes using visual illustration, literary description, imaginative sounds, and adroit movement with their bodies. The expressions visualized by Aaron Douglas and Claude McKay broke with tradition to give the world a look through their lens at alienation, the loss and despair of the African American, in efforts to embarrass society by observing its treatment of a race who had suffered and endured horrific treatment in their own adopted homeland. This modernist treatment during the Harlem Renaissance was successful in that the discomfort witnessed by the audience and readers of their works, brought about awareness of their crisis and allowed a venue for a display of their talents which gave rise to celebrate the African American as an individual and offered encouragement and support for all Americans to withstand injustice. Modernism in Home to Harlem and Song of the Towers 18 Works Cited Baker, Houston. “Modernism and the Harlem Renaissance”. American Quarterly 39.1 (1987): 84-97. JSTOR. Web. 21 Apr 2012. Cooper, Wayne. “Claude McKay and the New Negro of the 1920’s”. Phylon 25.3 (1964): 297306. JSTOR. Web. 21 Mar 2012. Davis, Donald. “Aaron Douglas of Fisk: Molder of Black Artists”. The Journal of Negro History 69.2 (1984): 95-99. JSTOR. Web. 13 Mar 2012. De A. R., I. “Harlem: Negro Metropolis by Claude McKay”. Phylon 2.1 (1941): 96-97. JSTOR. Web. 2 Jul 2012. Earle, Susan. “Aaron Douglas: African American Modernist”. CCA Reviews (2008): ArtIndex. Web. 21 Mar 2012. Hunt, Douglas. “Home to Harlem by Claude McKay”. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 140 (1928) 339-340. Kirschke, Amy. “The Depression Murals of Aaron Douglas: Radical Politics and African American Art”. TWU Libraries ILLiad. McKay, Claude. Home to Harlem. Ed. William L. Andrews. “Classic Fiction of the Harlem Renaissance. New York: Oxford UP, 1994. 101-237. Print. Powell, Richard. Rebirth, 1927; Crucifixion 1927; Into Bondage 1936; Aspects of Negro Life: Song of the Towers 1934. The Encyclopedia of the African and the African American Experience (2005): www.artlex.com. Oxford UP. Web. Smith, Robert. “Claude McKay: An Essay in Criticism”. Phylon 9.3 (1948): 270-73. JSTOR. Web. 2 Mar 2012.