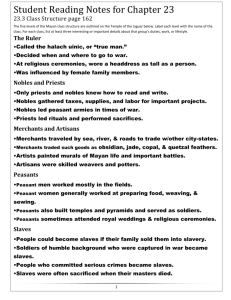

Maya Social Structure

advertisement

Maya Social Structure Maya society was rigidly divided between nobles, commoners, serfs, and slaves. The noble class was complex and specialized. Noble status and the occupation in which a noble served were passed on through elite family lineages. Nobles served as rulers, government officials, tribute collectors, military leaders, high priests, local administrators, cacao plantation managers, and trade expedition leaders. Nobles were literate and wealthy, and typically lived in the central areas of Maya cities. Commoners worked as farmers, laborers, and servants. It is believed that some commoners became quite wealthy through their work as artisans and merchants, and that upward mobility was allowed between classes through service in the military. Regardless, commoners were forbidden from wearing the clothes and symbols of nobility, and could not purchase or use luxury and exotic items. Commoners generally lived outside the central areas of towns and cities and worked individual and communal plots of land. The Maya had a system of serfdom and slavery. Serfs typically worked lands that belonged to the ruler or local town leader. There was an active slave trade in the Maya region, and commoners and elites were both permitted to own slaves. Individuals were enslaved as a form of punishment for certain crimes and for failing to pay back their debts. Prisoners of war who were not sacrificed would become slaves, and impoverished individuals sometimes sold themselves or family members into slavery. Slavery status was not passed on to the children of slaves. However, unwanted orphan children became slaves and were sometimes sacrificed during religious rituals. Slaves were usually sacrificed when their owners died so that they could continue in their service after death. If a man married a slave woman, he became a slave of the woman's owner. This was was also the case for women who married male slaves. _________________________________________________________________________ The top of the society was large and complex, consisting of the ruler, his family, their retainers, courtiers, and priests. Others, including the most skilled and influential architects, merchants, and craftsmen were also part of the noble elite, providing their skills were useful to the ruler. In both the priesthood and the ruling class, nepotism was apparently the prevailing system under which new members were chosen. Primogeniture was the form under which new kings were chosen as the king passed down his position to his son. After the birth of a heir, the kings performed a blood sacrifice by drawing blood from his own body as an offering to his ancestors. A human sacrifice was then offered at the time of a new king's installation in office. To be a king, one must have taken a captive in a war and that person is then used as the victim in his accession ceremony. This ritual is the most important of a king's life as it is the point at which he inherits the position as head of the lineage and leader of the city. The religious explanation that upheld the institution of kingship asserted that Maya rulers were necessary for continuance of the Universe. Religion was an important part of Mayan life that regulated almost everything. Priests were considered to Be the most important out of all the people in the Mayan tribes. They were usually the ruling chiefs and only they were educated to know all of what their gods meant (rituals, prayer, etc.). Each large city had one supreme chief who usually ruled over the city and the surrounding region for life. Upon his death, a son or brother took over. In some cases, the ruler's wife might be next in line. If no family successor was available, a new ruler was selected from the upper class. Each Mayan city or state also had several less important chieftains, who served jobs somewhat like our mayors. These men might have other occupations (other than a chieftain). They were considered the "leaders" of their Mayan city and they were also responsible for leading their people. Chieftains also served as judges and were held responsible for the consequences that applied for certain crimes. A thief became the servant of his victim. The murderers were put to death, sometimes as part of ritual sacrifice. For minor crimes, a criminal's hair was cut off as a sign of disgrace. There was a somewhat big separation between the life of the ruling class and that of the common people. Certain luxury items, such as jade, feathers, and jaguar pelts, were only to be used by members ruling class. It was the commoner's job to provide these items as offerings. When members of the upper class traveled, workers were expected to carry them in litters. Warriors were a separate class, whose main goal was to capture enemy prisoners. Sometimes farmers and other members of the lower class were forced to serve as soldiers. Captured enemy soldiers became slaves. Defeated officers became human sacrifices. Armies did not begin fighting until after an elaborate religious ceremony. Warriors wore feathered headdresses, and many carried bright pennants. In battle, soldiers carried shields made from thick animal hide. The warriors fought with wooden clubs, flint knives, spears, and slingshots. Warriors were also known to use hornet bombs, in which a hornet's nest was thrown into a group of enemy soldiers. All fighting stopped each evening, and there was a truce that lasted till morning. If any armies commander was wounded or killed, his army retreated and the battle ended. Beneath the noble rank were the general specialists, artisans, craftspeople, managers, and bureaucrats. These groups were ranked in importance and parallel the middle class of our society, only it was more difficult in the Mayan society to move up or within a group than it is today. Below the middle class were the essential service people; all the people responsible for making the city run. Information on these people is sketchy and has little supporting data. :46