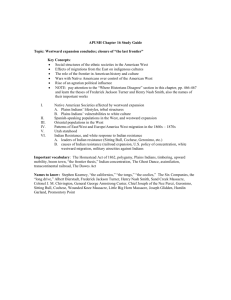

Chapter 17 Summary - Biloxi Public Schools

advertisement

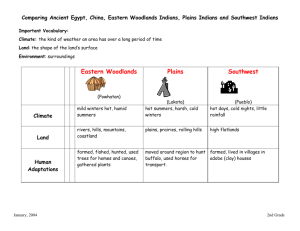

CHAPTER 17 THE WEST: EXPLOITING AN EMPIRE LEAN BEAR’S CHANGING WEST The author uses the visit of a Cheyenne chief, Lean Bear, to New York and Washington in 1863 to illustrate the lawless and brutal way the West was settled. Lincoln assured Lean Bear that the government wanted a peaceful and orderly migration into the West, but warned that many of the pioneers could not be restrained. A year later, U.S. soldiers killed Lean Bear in cold blood. BEYOND THE FRONTIER Beyond the Mississippi lay, according to contemporary maps, “The Great American Desert,” long thought to be uninhabitable by anyone but aborigines. By 1840 white settlement had paused at the edge of timber country in Missouri. Beyond lay the forbidding sea of grass that was the Great Plains. The eastern Prairie Plains had rich soil and good rainfall, but the rough High Plains were semiarid. The formidable Rockies and other mountain ranges held back rainfall, which rarely reached fifteen inches a year. The lack of water and timber and the ineffectiveness of traditional farming tools and methods led most early settlers to head directly for the more temperate Pacific Coast. CRUSHING THE NATIVE AMERICANS By 1867 nearly a quarter of a million Indians inhabited the western half of the United States. Some tribes were originally from the East, displaced by relentless waves of settlers. Others were native to the region, with cultures suited to their environments. By the 1880s, confrontations with still more white settlers had driven the Indians onto increasingly small reservations, and diseases introduced by whites had decimated the California Indians. By the 1890s the Indian cultures had crumbled. A. Life of the Plains Indians By the 1700s the availability of the horse had led the Plains Indians to abandon farming almost completely for a nomadic lifestyle, following and living off the vast herds of buffalo. The Plains Indians became skilled horse people, and tribes developed a warrior class, although their wars were usually limited to brief skirmishes and “counting coups,” touching the enemy’s body with the hand or a special stick. Tribes were divided into smaller, independent bands governed by a chief and council of elders. This loose organization within tribes confounded federal attempts to deal with the Indians. Tasks were divided between the sexes, but among tribes like the Sioux there was little difference in status between men and women. B. “As Long as Waters Run”: Searching for an Indian Policy Until the 1850s the lands west of the Mississippi were of no interest to whites. The United States government, therefore, regarded the trans-Mississippi West as one great Indian reservation, and as a final destination for the eastern Indians. When gold was discovered in California, however, the Great Plains became a thoroughfare to the Pacific, and the federal government began to attempt to confine the Indian tribes within specific areas. This attempt led to wars and massacres. As a result of the Sioux War of 1865-1867, Congress adopted a “small reservation” approach, designed to keep the Indians out of the path of white migration westward. C. Final Battles on the Plains The small reservation policy proved unsuccessful. Young warriors refused to be restrained, and white settlers encroached on Indian lands. The final series of wars featured a notable Sioux victory at Little Bighorn in 1876, but for the most part the Indians were defeated and often massacred. Such a massacre occurred at Wounded Knee in 1890, when the army became determined to stop the “Ghost Dances.” D. The End of Tribal Life The final step in the Indian policy was the assimilationists’‘ plan to use education, land policy, and federal law to eradicate tribal authority and culture. In 1887 Congress passed the Dawes Severalty Act, which destroyed communal ownership of land and gave small farms to each head of a family. Those Indians who left the tribe became United States citizens. A final, devastating blow to tribal life came when the buffalo, the very basis of the Plains Indians’‘ way of life, were exterminated by professional and amateur white hunters. Only about 250,000 Indians still inhabited the United States in 1900, and most lived in poverty. SETTLEMENT OF THE WEST Americans settled more land between 1870 and 1900 than at any other time in their history. Contrary to the safety-valve theory, most people moved west during periods of prosperity. Their timing was right, for as the nation’s population grew, so did the demand for the livestock, agricultural, mineral, and lumber products of the expanding West. A. Men and Women on the Overland Trail The great migration over the Plains began with the 1849 California Gold Rush. Large groups of settlers, including many families, usually started out from the area of St. Louis, Missouri, in April so that they could get through the Rocky Mountains before snow closed the passes. The trek to the Pacific Coast took at least six months and left in its wake epic stories of heroism and trails of garbage. B. Land for the Taking Between 1860 and 1900, the federal government distributed one-half billion acres of western land. Much was sold to states, private corporations, and individuals. About one hundred twenty-eight million acres were granted to railroad companies, and forty-eight million acres were given away through the Homestead Act of 1862. Although the act set off a mass migration of land-hungry Europeans and Americans, the size of the tracts granted was not suited to Plains conditions. The Timber Culture Act of 1873, which granted larger tracts to settlers who agreed to plant trees, was a success, but the Desert Land Act of 1877, which granted still larger tracts to settlers installing irrigation systems, invited fraud. Ultimately, most of the land in the West wound up in the hands of speculators, large ranchers, timber companies, and railroads. To boost their freight and passenger business, the railroads actively recruited immigrants and helped them buy, settle, and farm railroad property. The most important limit on population growth in the West was the scarcity of water. In 1902, in the Newlands Act, Congress set aside federal money for irrigation projects, transforming the arid West into a “hydraulic” society. C. Territorial Government Until statehood, the western territories functioned almost like colonies in which appointed governors and judges ruled without the consent of the settlers. These appointed officials became the center of patronage systems that continued even after statehood, and many Westerners made a living serving Congress. The territorial experience gave western politics a distinctly different character from the rest of the nation. D. The Spanish-Speaking Southwest The settlements of Spanish-speaking people concentrated in the Southwest and California made many cultural and institutional contributions, including irrigation, stock management, cloth weaving, and a set of laws for managing limited natural resources. Although the Californians began to lose their vast landholdings after the 1860s, the Spanish-Mexican heritage shaped politics, language, society, and law. THE BONANZA WEST The quest for mining, cattle, and land bonanzas led to uneven growth, boom-and-bust economic cycles, wasted resources, and “instant cities” like San Francisco. People came to get rich quickly and adopted institutions based on that mentality. A. The Mining Bonanza Mining first attracted settlers to the West, many to mine and as many to provide services to the miners. The mining frontier moved from West to East in a pattern first established by the California Gold Rush of 1849. First individual prospectors used simple placer mining to remove the surface gold. Then Easternand European-financed corporations moved in with the heavy, expensive mining equipment needed to remove metal from the deep lodes. The final fling came in the Black Hills rush of 1874-1876, in which miners overran the Sioux hunting grounds. Mining camps and germinal cities sprouted with each first strike, and urbanization quickly followed. The camps were governed by simple democracy and, when that failed, vigilantes. Men outnumbered women two-to-one, and “respectable” women were a rarity. Some women worked claims, but most earned wages as cooks, housekeepers, and seamstresses. Between one-quarter and one-half of camp citizens were foreign-born, and hostility was often directed against the French, Latin Americans, and Chinese. California’s 1850 Foreign Miner’s Tax drove foreigners out, and the federal Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 suspended Chinese immigration for ten years. The great mining boom ended in the 1890s. The western mines contributed millions to the economy, helped finance the Civil War and industrialization, and, through the new influx of silver, changed the relative value of silver and gold, the basis of American currency. Mining populated portions of the West and led to early statehood for Nevada, Idaho, and Montana. In its wake, however, it left invaded Indian reservations, pitted hills, and ghost towns. B. Gold from the Roots Up: The Cattle Bonanza The Far West offered an ideal region for cattle grazing. The buffalo grass of the Plains fattened the longhorn steers that provided meat for the cities of the East. Large herds grazed on the open range, then were driven to railheads, Abilene, or Dodge City, Kansas, most likely, where they then were taken by train to Chicago. The profits were enormous for the large ranchers, but cowboys, many of whom were African American or Mexican, worked long, hard hours for little pay. The cowboys, like the miners, governed themselves, and there was, contrary to popular legends, remarkably little violence among them. By 1880, the day of the cowboy was ending. Wheat farmers were beginning to fence off the open range, and mechanical improvements modernized the industry. As improved breeds proved profitable, more and more large ranches controlled by absentee owners opened on the northern ranges of the High Plains. Following the devastating winter of 1886 when thousands of cattle died, ranchers reduced the size of their herds or switched to raising sheep. C. Sodbusters on the Plains: The Farming Bonanza In the decades after 1870, millions of farmers moved west to seek crop bonanzas and a new way of life. By 1900, the Far West was a settled area and held 30 percent of the nation’s population. The farming frontier moved westward slowly, but steadily, and the population of the Plains tripled between 1870 and 1890. Of special interest was the migration of African Americans from the South, seeking to live free of discrimination and terror. All farmers on the Plains battled a harsh environment. Surface water was scarce, and digging deep wells and building windmills were both expensive operations. Lumber for fences and houses was scarce and expensive to import. Many started frontier life in dreary sod houses and endured extremes of heat and cold, an endless, enervating wind, and hordes of omnivorous grasshoppers. D. New Farming Methods Several important innovations allowed Americans to farm the Plains, such as barbed wire, which allowed fencing without wood, dry farming, which meant deeper farming and the use of mulch, and new strains of wheat that were resistant to harsh winters. Even so, the huge bonanza farms that cultivated thousands of acres were ruined by a period of drought between 1885 and 1890. It became apparent to most that small-scale, diversified farming was safer and more profitable. E. Discontent on the Farm Discouraged by droughts, some settlers abandoned their farms, and the ones who remained were restless and angry. They complained about declining crop prices, rising rail rates, and heavy mortgages. The Grange, originally founded to provide social, cultural, and educational opportunities for Southern farmers, grew and often acted as a political lobby. Farmers beyond the Mississippi also became more commercial, scientific, and productive. By 1890, they were exporting large amounts of wheat and other crops. F. The Final Fling Oklahoma, the last large area reserved for the Indians, was opened for white settlement in 1889. At noon on April 22, thousands of people rushed in to grab whatever they could, the epitome of Western history. CONCLUSION: THE MEANING OF THE WEST Historians have long interpreted the history of the Far West through the concept of the famous “frontier thesis.” More recently, however, the West is seen as a place where different ethnic and economic interests came into sharp conflict, and where rapid population growth eroded the environment, themes that continue to describe the West.