Click

CHAPTER 8

JUDICIAL

BRANCH

OFTEN, THE FORGOTTEN

BRANCH

PURPOSE?

PURPOSE:

Article 3 of the Constitution lays out the powers of the Judicial Branch.

Interprets laws and ensures that they are applied fairly

“The Judicial power of the United States shall be vested in one supreme court, and in such interior courts as the congress may from time-totime ordain and establish.”

DUAL SYSTEM

Under the Articles of Confederation, there was no national court system. Any law made by the Confederation was left up to the state courts to interpret which led to contradictory rulings and uncertainty about what the law really was.

The Constitution created a duel system: a justice system separated into state courts and a national (federal) court.

JUDICIARY ACT OF

1789- STRUCTURE

The original structure was left vague by the founders (by doing this, they avoided opposition in the ratification process).

Article 3: “The judicial power of the United States shall be vested in one Supreme Court, and in such inferior courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish.

”

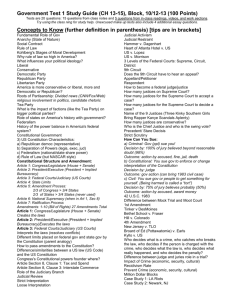

Judiciary Act of 1789- Proposes the three-tiered system:

1) District Courts

2) Circuit Court of Appeals

3) Supreme Court.

STRUCTURE

SCOTUS

(Supreme Court of the United States)

(80%-85%) appeal

(15%-20%) appeal

State Supreme Court

U.S. Court of Appeals appeal appeal

U.S. District Court

Federal Court System

( ~ 1 million cases/year)

Intermediate Court of Appeals appeal

Municipal or County Court

State Court System

(~ 30 million cases/year)

JURISDICTION

Jurisdiction : Court’s authority to hear and decide cases.

1. State Jurisdiction : authority to decide cases over state laws in which the federal government doesn’t have exclusive jurisdiction.

Municipal and County Courts => Intermediate courts => State Supreme Court

2. Exclusive Jurisdiction : authority of a court to hear a case which excludes other courts from hearing that case.

3. Federal Jurisdiction : authority of a court to hear cases that apply strictly to federal laws.

District Courts => Circuit Court of Appeals => and Supreme Court

FEDERAL

JURISDICTION

What does Exclusive Jurisdiction cover?

1. Involving Constitution Interpretation

2. Violations of Federal Law

3. Controversies b/t states and Parties b/t states

4. Suits involving the federal government

(if you sue the federal government)

5. Cases involving foreign countries

FEDERALISM:

CONFLICT OF POWER

If a criminal act violates both a federal and state law, the federal U.S. attorney has the right to take the case or refuse the case?

- Example: Possession of Cocaine

- Federal courts usually provide more harsh sentencing.

How can this lead to a lack of “equal” justice?

- How is the court system an example of how federalism functions?

WHO EXERCISES

POWER- JUDGES

Why are judges appointed?

1. Legal Expertise

2. Senatorial courtesy: traditionally, the senators do not approve of a appointment of a judge (primarily at the district level) if the senator from the state of that judge or from the party of the president wants to deny that appointee.

This forces the president to have to consult the senators first or make decisions off their recommendations.

3. Party Affiliation-Political philosophy

4. Judicial Philosophy:

Judicial restraint: the belief that a judge should interpret the

Constitution according to the framers’ original intention.

Judicial activism: the belief that judges can adapt the meaning of the

Constitution to meet the demands of contemporary realities and interpret the Constitution as an evolving document.

DISTRICT COURTS

“Law and Order Court”- Trial Court

Witnesses, Juries, Evidence

94 federal District courts

Original Jurisdiction: authority to hear cases for the first time

DISTRICT COURTS

- In the absence of a Supreme Court ruling to the contrary, the lower federal courts determine what the law is by setting precedents in their rulings.

- In serious criminal cases, district courts convene panels, grand juries, to hear evidence of a possible crime and to recommend whether the evidence is sufficient to file criminal charges.

- District courts hear bankruptcy cases. Bankruptcy is a legal process by which persons who cannot pay money they own others can receive court protection and assistance in settling their financial problems.

- Judges preside over a trial. S/he makes sure trials follow proper legal procedures to ensure fair outcomes. If participants refuse a jury, the judge can act as the jury.

UNITED STATES CIRCUIT

COURT OF APPEALS

Appellate Jurisdiction: authority to hear a case appealed from a lower court.

Review the decisions of lower courts

Decisions:

1.

Uphold the original decision

2.

Reverse the original decision

3.

Remand- send back to lower courts for retrial.

Not deciding guilt or innocence. Examining if the lower court made the correct legal interpretation.

Appeals courts don’t have to take cases.

UNITED STATES CIRCUIT

COURT OF APPEALS

13 Circuit Courts- 11 regional, 1 for D.C., and 1 federal court which covers all Americans.

Appellate court- Only guilty defendants can appeal.

Those found not guilty are let free. In civil cases

(questions of civil rights), either side can appeal.

- Few cases are successfully appealed. In 2009, only

9% were successfully appealed.

- They do not retry cases. They review procedural errors.

- Decisions of one circuit court is not binding to other circuit courts.

COMMON LAW

Opinion- written explanation by judge or group of judges of the legal thinking behind a decision.

The Opinion sets the precedent.

Precedent: an earlier decision or action that guides future decisions and actions.

Precedent is not law, but it must be followed due to stare decisis (stair-ray-d-si-ses).

Stare Decisis: the rule stating that precedent must be followed providing a legal system with predictability and stability.

Followed by the same courts or lower courts.

SUPREME COURT OF THE

UNITED STATES (SCOTUS)

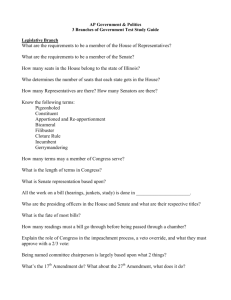

(Back Row): Sonia Sotomayor, Stephen Breyer, Samuel Alito, Elena

Kegan (Front Row): Clarence Thomas, Antonin Scalia, John Roberts,

Anthony Kennedy, and Ruth Bader Ginsburg

SCOTUS

9 Justices (1 of which is Chief Justice)

Majority of Justices is needed to decide a case.

Qualifications?

Removal: hold position for life (good behavior)

Impeachment

Retire

Death

Appointed by the President and approved by the Senate

Purpose: proper interpretation of the law…not innocence or guilt

“Equal Justice for All” = Their decisions (precedents) will protect every citizen equally, commonly (Common Law)

AUTHORITY

Limited Original Jurisdiction:

Certain cases where the state is a party

Cases involving foreign representatives

Judicial Review: the power to determine whether any federal, state, or local law or government action is constitutional or not.

PRECEDENT FOR JUDICIAL

REVIEW- MARBURY V. MADISON

Question: If a law by the legislative branch conflicts with the

Constitution, can it be determined to be unconstitutional by the Judicial

Branch?

Answer: Yes!

Precedent: The Constitution is the highest power in the land, and the

Judicial Branch has the power to interpret whether the legislative or executive branch has violated the Constitution…hence, confirming the power of Judicial Review.

The purpose of judicial review is as a check:

“Limitations [on the powers of government]…can be preserved in practice no other way than through…courts of justice, whose duty it must be to declare all acts contrary to the manifest tenor [obvious meaning] of the Constitution void. Without this, all the reservations of particular rights or privileges would amount to nothing.”

- Alexander Hamilton, The Federalist No. 78

EXPANDING FEDERAL

POWER- JOHN

MARSHALL’S COURT

John Marshall expended the power of the Judicial Branch and the federal government by using judicial review in

Marbury v. Madison.

This action would create a precedent for an expansion of federal power in the judicial branch and, eventually, the power would continue to expanded to other federal branches in court decisions like McCulloch v. Maryland and Gibbons v.

Ogden.

PROCESS OF SCOTUS TO HEAR

A CASE (7 STEP PROCESS)

1. SCOTUS must be informed of a case in which to review.

Petition of Certiorari (sir-shore-rare-eye):

Formal application by a party to have the

Supreme Court of the United States to review their case.

Latin for “to be informed”

SCOTUS has the discretion to approve or deny any such application.

~9000 petitions/year => SCOTUS => avg. 67-80 cases/year = less than 1%

2. Meeting by Justices to choose cases

Rule of Four: Four Justices must agree to

HEAR a case (not decide one)

Issue a writ of certiorari: an order to a lower court to deliver its record in a case to a higher court for review.

Accepted cases go on the DOCKET: calendar with a list of cases

Try to pick cases that have national implications, not specific individuals or groups.

EXAMPLE OF A DOCKET

3. Written Arguments-

Briefs: written document explaining one side’s position on the case.

Amicus Brief: a brief prepared by outside parties who have an interest in the case.

4. Oral Arguments- 30 minute oral presentation of each side’s position with questions from the

Justices.

5. ConferenceAll Justices meet in their “chambers”

(no one else can attend conference).

Chief Justice resides over conference.

Vote on case.

More cases are 9-0 than 5-4. What does this tell us?

6. Opinion writing-

Majority Opinion: presents views of the majority of justices. Explains how the court came to its decision, and acts as the precedent for the case.

Dissenting Opinion: the arguments which show views contrary to the majority.

Concurring Opinion: the opinion of a member

(members) who voted with the majority, but for a different interpretation of the law.

7. Announcement- Public announcement of the decision.

DRIVING FORCES

BEHIND JUDICIAL

DECISIONS

1. Precedent, but the court can overrule a former decision (example: Plessy v.

Ferguson and Brown v. Board)

2. Legal views (strict interpretation/loose interpretation- what is the role of the court)

3. Personal beliefs

4. State of society (example: gay marriage)

District of Columbia v. Heller

Argued March 19, 2008

Decided June 26, 2008

Facts

The Second Amendment protects “the right to keep and bear arms,” but there has been an ongoing national debate about exactly what this phrase means. Many lower courts have ruled that reasonable gun regulations, like handgun registration, are allowed under the Amendment. Others continue to argue, however, that any gun regulation deprives individuals of their constitutional right to bear arms. This case, which is about whether the District of Columbia can ban handguns altogether, squarely addresses this debate and the meaning of the Second Amendment.

In 1976, the District of Columbia enacted strict gun control laws, including a ban on all handguns and a requirement that all other guns in homes be kept unloaded and disassembled (or bound by a trigger lock). Dick Heller and five other D.C. residents challenged these regulations in 2003, claiming that they need functional guns in their homes for self-defense. They did not object to a registration requirement for their guns nor did they seek to carry them outside their homes.

The federal trial court upheld D.C.’s gun control laws. But the federal court of appeals reversed, ruling that the Second Amendment protects an individual right to keep and bear arms and that handguns are “arms” covered by the Amendment. The District of

Columbia appealed to the Supreme Court, and for the first time in almost seventy years, the Court agreed to hear a case on the central meaning of the Second Amendment.

Issues:

Do the D.C. provisions violate the Second

Amendment rights of individuals who are not affiliated with any state-regulated militia (like the

National Guard), but who wish to keep handguns and other firearms for private use in their homes?

Constitutional Amendments and Cases:

The Second Amendment, U.S. Constitution

A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.

U.S. v. Miller (1939)

U.S. v. Miller is the only Supreme Court decision to directly address the meaning of the

Second Amendment. In this case, the defendants, Jack Miller and Frank Layton, were suspected bank robbers and moonshiners being watched by agents of the Department of the Treasury. In 1938, they were arrested for transporting an unlicensed, sawed-off shotgun across state lines while engaged in interstate commerce, in violation of the

National Firearms Act (“NFA”). Miller and Layton appealed their conviction, arguing that the NFA violated the Second Amendment.

The Supreme Court held that this application of the NFA did not violate the Second

Amendment. It explained that “[i]n the absence of any evidence tending to show that possession or use of a ‘shotgun having a barrel of less than eighteen inches in length’ at this time has some reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia, we cannot say that the Second Amendment guarantees the right to keep and bear such an instrument. Certainly it is not within judicial notice that this weapon is any part of the ordinary military equipment of that its use could contribute to the common defense.”

Arguments for the District of Columbia

The Second Amendment relates to the right of government-organized militia, not private citizens, to possess arms. In fact, “arms” was the historic term for military weapons, and the Amendment was originally adopted to allow states to protect themselves from a tyrannical federal government.

Like the short-barrel shotguns in Miller, the handguns in D.C. are not necessary for the “preservation or efficiency” of a militia.

Government has the obligation to protect public safety and therefore courts that review gun control laws should require only that the laws be a reasonable effort to do so.

Less restrictive government means for preventing gun deaths—such as an FBI background check—would not be adequate since citizens who lack a criminal history commit many of the nation’s murders.

Guns were and continue to be dangerous weapons. At the time of the law’s passage, handguns were used in the majority of armed robberies, armed assaults, murders, and rapes. There is also a link between handguns and accidental deaths and injuries, particularly involving small children.

Overturning the District of Columbia’s law would call into question the constitutionality of federal, state and local gun-control laws and regulations throughout the country and lead to a flood of lawsuits to overturn those gun laws.

Arguments for Heller

The Second Amendment protects a private individual’s right to own guns. At the time the Amendment was adopted, militiamen used their own private guns when they served in the state militia

Under Miller, arms that would be useful in militia service, like handguns, cannot be banned.

Because the right to bear arms is fundamental, when courts review guncontrol laws they should apply a strict standard and only allow these laws to stand when the government can show that it has a very important interest that is advanced by the law.

The outright handgun ban is not the best means to achieve the government’s goal in reducing crime: an FBI background check of the purchaser would sufficiently meet this goal without infringing on the Second Amendment right.

The right to bear arms protects two of the most fundamental rights – the defense of one’s life inside one’s home, and the defense of society against government misuse of authority.

No state and only one other city (Chicago) bans handguns outright. It is important for the nation’s capital to obey the Constitution and set an example for other states and cities.

Decision:

Justice Scalia delivered the majority opinion in which Chief Justice Roberts and Justices

Kennedy, Thomas and Alito joined. Justice Stevens wrote a dissent in which Justices Souter,

Ginsburg and Breyer joined, and Justice Breyer wrote a dissent in which Justices Stevens,

Souter and Ginsburg joined.

Majority:

In a 5-4 decision, the Court struck down the District of Columbia’s ban on handguns, holding that the Second Amendment guarantees an individual right to gun ownership.

The justices first examined the text of the Second Amendment in two separate parts: “A well regulated militia being necessary to the security of a free state,” and “the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed.” They determined that the purpose of the first phrase was to explain why the Framers thought that the right to bear arms was important. Its purpose was not to limit this right to those in the military.

The majority then explored the development of the right to bear arms throughout history.

They examined English laws from the 1600s and 1700s as well as several state constitutions written at the same time as the Constitution and Bill of Rights. These laws recognized an inherent right for individuals to possess weapons for self-defense. According to the Court, the Framers recognized that the right of individuals to bear arms was a fundamental right existing even before the Bill of Right. They included the Second Amendment to protect this pre-existing individual right, not to create a new right that would only apply to those in the military.

The justices agreed, however, that the right to bear arms is not absolute. It only guarantees the right to posses guns which, like handguns, are “in common use at the time,” while still allowing the government to outlaw other types of guns. In addition, reasonable regulations such as licensing requirements, laws preventing felons from owning firearms, and laws forbidding the carrying of guns into school zones do not violate the Second Amendment.