Plaintiff

advertisement

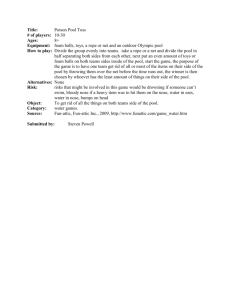

Sanneh, Naito, Anacker 1 Aja Sanneh, Natalie Naito, Jordan Anacker October 26, 2012 Economics 495 Foreman v R and L Builders: Plaintiff Brief The case before us involves an acknowledged breach of contract. The issue at stake in this case is whether our client, Foreman, should be awarded damages based on the ‘cost of performance’ rule or the ‘value’ rule. Foreman and R and L Builders entered into a contract to build our client, Foreman a pool in her backyard. The total cost was to be $100,000. The contract expressly provides the maximum depth of the pool to be 7’6’’, but upon the completion of the pool, Foreman realized the maximum depth of the pool was only 6’9,’’ nine inches shallower than agreed upon. Our goal in this case is to recover as damages the cost of demolition of the existing pool and construction of a new one of the required depth. In this brief, we will begin by discussing the additional facts of the case, not to discredit them, but to illuminate their narrow scope. We will then predict and refute the arguments of the defense while presenting our own. Lastly, we will offer the economic advantages for granting Foreman damages of $33,000 and disadvantages of awarding only $4,000. The additional information provided in the facts of the case, such as the pool is still safe to dive into, are irrelevant. Though the pool is deemed safe to dive into, Foreman expressly called for a 7’6’’ deep pool—the courts cannot negate her demand for a certain depth by asserting the safety of a shallower pool. The next fact is that the shortfall in depth of the pool does not detract from its value. Again, to Foreman, who expected a pool 9 inches deeper than what was completed, the value of the pool is indeed less. Foreman may be taller than 6 feet or Sanneh, Naito, Anacker 2 entertains taller people who cannot fully enjoy the pool due to its lack of depth. The third fact stating the necessity to destruct the entire pool in order to make it the required depth is not relevant to Foreman. She made a contract and R and L Builders choose to breach it; the $33,000 costs to fix the pool as Foreman desired falls to them, not to Foreman. Though no evidence can prove Foreman will use this $33,000 to rebuild the pool, there is also no evidence that she won’t use it to build her desired pool. And while an ‘expert witness’ quantifies Foreman’s loss of amenity at $4,000, the opinion of one expert is too narrow and subjective. In addition to these facts, the defense will bring two main arguments against the plaintiff. The defense will argue two key points to undermine my client’s rights to full damages. First, they will argue that the language of the pool’s depth was a boundary not a requirement. The contract states that the maximum depth of the pool was to be 7’6’’ but it does not explicitly state that was to be the deepest depth of the pool. I counter this argument by citing Otis Wood v Lucy Duff-Gordon (1917). The contract implies that the pools deepest point was to be 7’6’’, just as the contract between Wood and Duff-Gordon implies that Wood would indeed endorse Duff-Gordon. The purpose of including the depth was to state 7’6’’ as the deepest, not as a hypothetical depth. The economic precedent of the Supreme Court of New York in Wood v Duff-Gordon was to save contracting costs by allowing parts of the contract to be ‘filled’ with implications. If every minute detail were to be verbalized in contracts, costs would be high enough to deter parties from entering into contracts at all. The language of the contract is clear, and the depth requirement is fairly implied. When examining breached contracts, we must assume all valid contracts are Pareto-Improving, and for that reason examine each party’s intent rather than the efficiency of the contract. There is no contention in this case that both parties wholly accepted the contract including the specified terms of the pool’s depth. Both parties would not agree to the terms if they did not think they would be better off after fulfilling the contract. To Foreman, having Sanneh, Naito, Anacker 3 a pool with depth 7’6” was worth at bare minimum $100,000 if not more. Similarly, to R & L must have assumed they could build the pool at the specified depth and still make a profit. For this reason, the court must focus on each party’s intentions, not the efficiency of the contract made. The defense in this case will undoubtedly cite Peevyhouse v. Garland Coal and Mining Co., as an opposing legal president. While at a glance this may appear as a valid counter, upon further examination, there are two key problems with the case’s application here. First, as stated in the opinion “the primary purpose of the lease contract between plaintiffs and defendant was neither 'building and construction' nor 'grading and excavation'. It was merely to accomplish the economical recovery and marketing of coal from the premises, to the profit of all parties.” Unlike Foreman, Peevyhouse’s motive for agreeing to the contract was to make profit, and he leveraged his land to do so. The remedial work that was not done was “incidental to the main objective” which was to make a profit. As such, the judge treated the case as a business deal, awarding damages in to Peevyhouse in the amount of lost profits from the breach of contract, not the cost of performance. Framing the case at hand in the same light as Peevyhouse is incorrect because of the distinctly different intentions behind the contracts. Foreman did not contract to build his pool as an investment in his land in the way that Peevyhouse leased his land to be mined. Rather Foreman contracted the pool for personal use, to gain utility from his land, regardless of market considerations. In that light, clearly the value rule applied in the Peevyhouse case cannot be similarly applied to this case because of the key differences in intention. According to Wunder, in handling the intentional breaches in contracts, “the law aims to give the disappointed promisee, so far as money will do it, what he was promised.” Foreman spent $100,000 for a pool that was to be worth $100,000. The missing 9 inches of the pool directly detracts from its value. The court in Wunder ruled that the value of the land is not appropriate to measure damages for a willful breach of a building contract, and we agree. Additionally, the ruling in Chamberlain v. Parker states Sanneh, Naito, Anacker 4 that a property owner has a right to recover what “he has been promised, for which he has paid, and of which he has been deprived by the contractor’s breach.” Foreman was “entitled to a specific performance of the contract and since the defendant has failed to perform, the proper measure of damages should be the cost of performance. Any other measure of damage would be holding for naught the express provisions of the contract;” it would be taking the benefits from the plaintiff and giving them to the defendants who failed to perform its obligations. It is not fair for R and L Builders to first willfully breach the contract and then not pay full damages ($33,000) just because Foreman’s loss of amenity is estimated at $4,000. In Jacob & Young, Inc v Kent Justice Cardozo stressed that “the willful transgressor must accept the penalty of his transgression” and in this case that is damages measured by cost of performance. The economic consequences are clear. R and L Builders signed a contract promising to build and enclose Foreman’s pool as she specified. But R and L Builders acted in bad faith; they willfully broke that contract and are attempting to evade full damages. Contracts are ParetoImproving; no one enters a contract unless they are better off than before. R and L Builders “accepted and reaped the benefits of its contract and now urges that the plaintiffs’ benefits under the contract be denied” (Peevyhouse v Garland Coal & Mining Co). If the courts allow the defendant to avoid due punishment, the precedent will be to encourage predatory business to take undo advantage of clients. R and L Builders cut their costs by building a pool 9 inches shallower than promised and their punishment should be not to pay amenity damages to Foreman, but to pay the full $33,000 to rebuild her pool as desired. The fundamental function of contract law is to deter parties from behaving opportunistically. Foreman is not an expert in pool contracts but to the best of her ability, she outlined her express wishes in the contract with R and L Builders. She wanted the maximum Sanneh, Naito, Anacker 5 depth (the deepest part of the pool) to be 7’ 6’’. R and L did less work by making a more shallow pool. They used less building material and spent fewer hours of labor. They may have spent that time working for a different project, thus increasing profits rather than expending costs. I admit, these numbers are difficult to quantify, but it is possible that R and L Builders saved on labor, materials, and time more than the $4,000 the defendants deem acceptable damages. If this behavior is not curtailed, businesses will be encouraged by the judiciary system to take advantage of individuals. Though the defense may justify granting Foreman just $4,000 by quoting Posner in Walgreen Co v Sara Creek Property Co “it is better to give a wronged person a crude remedy than none at all,” the best and most just remedy in this case is $33,000 not $4,000. In summation, Foreman’s damages should be measured by cost of performance, not value rule. The defendant intentionally breached a contract, displaying predatory business behavior and acting in bad faith. As a professional contractor, surely the defendant was in the best position to know the costs of constructing the contracted pool, thus having no reason to breach it. The majority opinion of Peevyhouse v Garland Coal & Mining Co should be overruled, and the majority decision in Groves v John Wunder Co. should be upheld. The courts can finally cement precedent by ruling in favor of Foreman. Full damages at $33,000 will deter future businesses from breaching contracts because it is beneficial for them to do so. It will also keep contracting costs down in terms of filling gaps.