opd-CompStatePlan-2012-2018

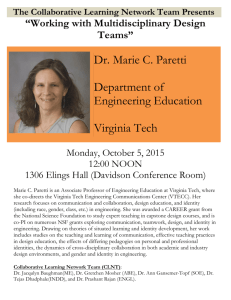

advertisement