CONSEQUENTIALISM Consequentialism: the rightness or

advertisement

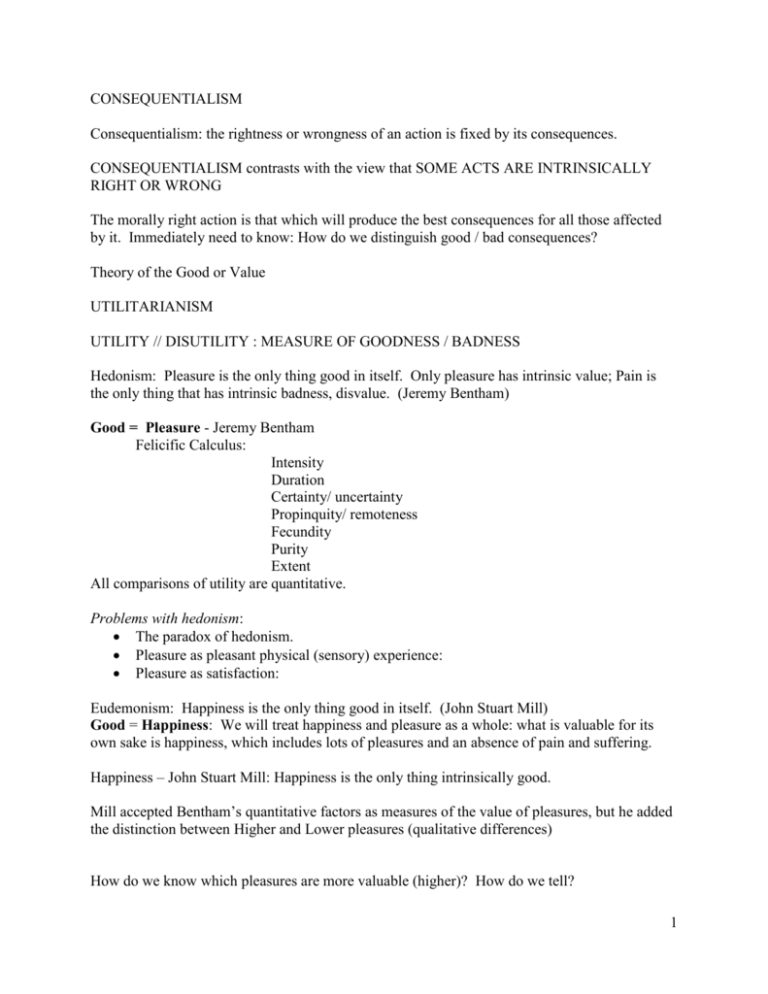

CONSEQUENTIALISM Consequentialism: the rightness or wrongness of an action is fixed by its consequences. CONSEQUENTIALISM contrasts with the view that SOME ACTS ARE INTRINSICALLY RIGHT OR WRONG The morally right action is that which will produce the best consequences for all those affected by it. Immediately need to know: How do we distinguish good / bad consequences? Theory of the Good or Value UTILITARIANISM UTILITY // DISUTILITY : MEASURE OF GOODNESS / BADNESS Hedonism: Pleasure is the only thing good in itself. Only pleasure has intrinsic value; Pain is the only thing that has intrinsic badness, disvalue. (Jeremy Bentham) Good = Pleasure - Jeremy Bentham Felicific Calculus: Intensity Duration Certainty/ uncertainty Propinquity/ remoteness Fecundity Purity Extent All comparisons of utility are quantitative. Problems with hedonism: The paradox of hedonism. Pleasure as pleasant physical (sensory) experience: Pleasure as satisfaction: Eudemonism: Happiness is the only thing good in itself. (John Stuart Mill) Good = Happiness: We will treat happiness and pleasure as a whole: what is valuable for its own sake is happiness, which includes lots of pleasures and an absence of pain and suffering. Happiness – John Stuart Mill: Happiness is the only thing intrinsically good. Mill accepted Bentham’s quantitative factors as measures of the value of pleasures, but he added the distinction between Higher and Lower pleasures (qualitative differences) How do we know which pleasures are more valuable (higher)? How do we tell? 1 Test of quality of pleasures: “Of two pleasures, if there be one to which all or almost all who have experience of both give a decided preference, irrespective of any feelings of moral obligation to prefer it, that is the more desirable pleasure.” We should defer to the judgment of those who are competently acquainted with both. (The Competent Judge Test) “It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied. And if the fool, or the pig, are of a different opinion, it is because they only know their own side of the question.” (92) There is a difference in kind, not merely a difference in degree, between pleasures. Nobler pleasures make their possessors happier. Nobler pleasures also make other people happier. Hedonism and happiness are both states of mind, subjective states. Utilitarianism uses a subjective theory of value. In general, there are problems with any subjective theory of value grass counters Robert Nozick’s Experience Machine Consequentialism need not take that form: Intrinsically good things – G.E. Moore Desire or preference satisfaction – many contemporary proponents Questions about ends are questions about what is desirable. Utilitarian say happiness is desirable, and the only thing desirable, as an end in itself; all other things are desirable only as a means to that end. Only proof that an object is visible is that people see it. Only proof that a sound is audible is that people hear it. Only proof that something is desirable is that people desire it. Calculation of net utility: Identify the characteristic(s) by virtue of which a state of affairs is good, rank states of affairs from best to worst, as judged from an impartial perspective. Calculation of expected utility: add probabilities. PRINCIPLE OF UTILITY: Maximization (greatest happiness of greatest number) From Good to Right, Duty, Obligation, Virtue “According to the greatest happiness principle, …the ultimate end, with reference to and for the sake of which all other things are desirable—whether we are considering our own good or that of other people—is an existence exempt as far as possible from pain, and as rich as possible in enjoyments, both in point of quantity and quality…” (94) 2 Morality, the rules and precepts of human conduct, are those the observance of which secure to mankind the greatest happiness. And when possible, to all sentient creatures. Individuals / governments Egalitarian Impartial System for Education, Social Arrangement and Laws. 2 Choices that Need to be Made 1. Act / Rule Utilitarianism 2. Greatest overall amount of good / greatest average utility (e.g., population ethics) Virtues of Consequentialism 1. Simplicity 2. Psychological realism 3. Intuitive plausibility Problems of Consequentialism 1. sometimes has very counter-intuitive implications 2. the ends always justify the means (act), which leads us to (rule) to fix, but 3. requires extraordinary calculations, very onerous decision procedure, which leads us to (rule) to fix, but 4. rule worship, irrational instruction 5. impartiality requires too much of us 6. both Bentham and Mill commit the ‘fallacy of composition’. Mill says, “each person’s happiness is a good to that person, and the general happiness, therefore, a good to the aggregate of all persons”. (95) We can come to value other things than happiness or pleasure for themselves, and desire them for their own sake. Mill: everything else we value first as a means, because it tends to produce the greatest good, even virtue. But what is first valued as a means comes to be valued for its own sake. Then people take pleasure from it directly. So it ultimately serves utility. Other things we desire for their own sake. Only virtue is always conducive to the general happiness of all, and so love of virtue is cultivated without limit. 3 John Rawls, Two Concepts of Rules Rawls did not support utilitarianism, but he thought that a kind of criticism of it was mistaken. We used that kind of criticism when we said that utilitarianism would tell us that we have to punish an innocent person or break a promise if doing so would produce the best consequences, all things considered in the circumstances. Legal (Criminal) Punishment: justifications of punishment have been dominated by Retributivism and Utilitarianism both views have intuitive force Can be reconciled by distinguishing between (1) the rule governed practice of law and punishment, and (2) actions taken in accordance with or under the rules of the practice. When deciding whether to adopt a system of laws and punishments, we use utilitarian reasoning to decide which practice of punishment would be best or would be justified. Once we have adopted the practice of punishment, consisting of rules to be applied and enforced, we need to use retributive reasoning to justify the application of the rules to any particular case (particular instance of punishing under the rules). In HLA Hart’s terminology, we distinguish between (1) the General Justifying Aim of using a system of criminal laws which includes punishment for violators, and questions of (2) its distribution (whom should be punished) and (3) amount (how severely we should punish). (1) Should be answered using Utilitarianism (only if the benefits outweigh the costs) (2) And (3) Should be answered using Retributivism (only the guilty and as much as they deserve) Why do we have the institution of punishment; what justifies the choice of this practice? Vs Why did we punish some particular person (what justifies this specific application of the rules)? Distinguish between the justification of an institution or rule-governed practice from the justification of a particular action falling under it. Telishment Promises Utilitarianism is thought to say that we should only keep promises when doing so will maximize utility. But on such a view, promises do not create obligations of any force. Even if we fully take into account the effect our breaking our promise might have on the practice of promising (eroding confidence, undermining legitimate expectations, etc.), it might still be best sometimes to break our promises. But generally, good consequences are not the kind of consideration that provides a justification or defence for breaking a promise. That is what gives promising its value as a practice. 4 Rawls uses same strategy: the practice of promising, and treating the obligations that promises create as very strict, is very beneficial. Promising as a practice would be justified by Utilitarianism. Then, keeping your promise is required by the practice. Applying utilitarian reasoning directly to the decision to keep or break your promise is to fail to act as the practice requires. Explanation of the error (error theory): 2 conceptions of rules Summary View of Rules. Rules of thumb within direct application of the principle of utility. Practice Conception of Rules. Rules define a practice, and it is the rule-constituted practice that is to be assessed by the Utilitarianism principle. Failure to make this distinction, and the tendency to treat all rules as summary rules, may account for why so many philosophers have thought Utilitarianism is vulnerable to these objections. They both involve practices in which rules constitute the practice rather than function as rules of thumb. The principle of Utilitarianism applies at different levels in the two cases. Peter Singer, Rich and Poor Principle: if it is in our power to prevent something very bad from happening, without sacrificing anything of comparable moral significance, then we ought to do it. Principle demands that we give substantially to the poor. Absolute poverty vs Relative poverty Absolute wealth/affluence: income sufficient to meet all essential needs with some left over. So they could transfer some of their wealth to the poor without threatening their basic welfare. IF allowing someone to die is not morally different than killing someone, then we are all murderers. Five differences between killing and letting die: 1) Motives (reckless) 2) Not killing is easy; fulfilling a duty to save, thereby giving away all our surplus wealth, is hard (ease of discharge of the duties) 3) Certainty of outcomes (reckless) 4) Unidentifiable victims 5) Direct responsibility vs something we are not responsible for 5 These are all “extrinsic” and contingent difference between killing and letting die. But they do not challenge the claim that killing and letting die are intrinsically equivalent. An obligation to assist: Cases of easy rescue Argument formally laid out on p. 135 Objections to the obligation to assist: 1) Take care of our own first 2) Property rights 3) Population and the ethics of triage and life-boats No obligation to assist if our aid will not benefit the people 4) Government responsibility, not individuals’ duty (.7% target of GDP not met) 5) Too high a standard, too demanding (perhaps 10%) 6