Day 5-7-1

advertisement

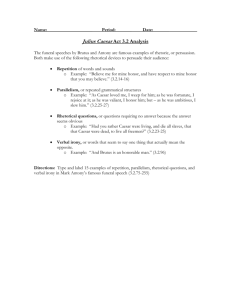

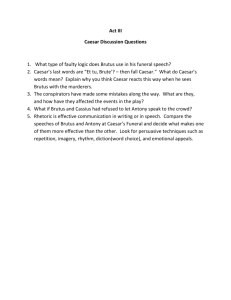

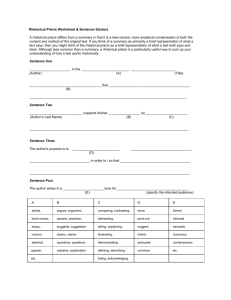

Invitational Summer Institute Tuesday, July 1, 2014 Day 5 Agenda Tuesday, July 1, 2014 9:00-9:15 Daily Log: Lauren Author’s Chair 9:15-10:30 Demonstration Lesson: Anush Break 10:45-11:15 Demo Lesson Response 11:15-12:00 Teaching Revision: Kathy 12:00-1:00 Lunch 1:00-1:30 Writer’s Workshop; Pam & Kathy 1:30-2:15 Reading Time: Pathways 2:45-3:25 Introduction to Inquiry Groups 3:25-3:30 Wrap-up Lab tomorrow Explore technology readings on flash drive for tomorrow Demo lessons 4-6 come with lesson plan draft Thursday Formatting demo lesson slides Daily Log Author’s Chair What I Learned… Connecting personal experences through a poem. One word can lead to a mouthful. Steps in “poetry council” A new way to engage students with poetry A new way to have discussion within the classroom That I have something to share That some people fear failure but try anyway What I learned… What spontaneous writing can do to stimulate deep thought and how that deep thought can have a great effect on others How to use council in an academic content area How even when you have nothing to write about, you still write some pretty profound, personal, and beautiful and even humorous stuff Integrating technology is a struggle for everyone What I learned… The importance of pre-writing (freewriting) when it is timed About poetry councils—tons of great ideas for classrooms I love memory writing. I could have spent my whole writing time cycling from one memory to the next. What I learned… How to use council for something other than behavior Just try 1 new thing each year when it cmes to technology Surprises and questions Freewriting evolves from where you are How many of us have shared experience and concerns re using technology in the classroom How many edits I did during writing time How much I have to say and am willing to share How good it can feel to share your writing The writing I did was very funny and I’m glad it made my group laugh. Surprises and questions How brave my group mates were in sharing very personal writings How easily we are able to share personal things with one another. It’s beautiful. Next time… I want to know more about the circle and other ways to set it up when the class cannot be in a literal circle Adapting writing lessons for students with learning disabilities More revision strategies Always want more starter writing activities—ways to get the gears cranking Good websites for blog/wiki hosting Rhetorical Précis ANUSH ALEKSANYAN Research From Reading Rhetorically by John C. Bean, Virginia A. Chappell, and Alice M. Gillam Margaret K. Woodworth. Rhetoric Review, Vol.7, No.1. (Autumn, 1988), pp. 156-164. ERWC: English Reading Writing Curriculum The CCR Anchor Standards CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.9-10.1(A-E): Write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts, using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence. CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.9-10.2(A-F): Write informative/explanatory texts to examine and convey complex ideas, concepts, and information clearly and accurately through the effective selection, organization, and analysis of content. CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.9-10.4: Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience. WHY PRÉCIS? STUDENTS NEED TO GO BEYOND SIMPLE SUMMARY WHEN WRITING ABOUT TEXTS STUDENTS OFTEN GET OFF TANGENT, AND EXPERIENCE DIFFICULTY AND LACK FOCUSE WHEN SUMMARIZING TEXTS STUDENTS TEND TO PARAPHRASE MORE RATHER THAN SUMMARIZE WHAT IS RHETORICAL PRÉCIS? The Research A précis is a structured piece of writing that will help students “assess the rhetorical strategy of the author, the form of the discourse, the author's purpose or hidden agenda, and the nature of the audience being addressed. To lift information out of its rhetorical context is potentially dangerous; to do so perpetuates the myth that whatever is in print is true, and it further isolates student writers from the authors who are speaking to them” (Woodworth). Margaret K. Woodworth. Rhetoric Review, Vol. 7, No. 1. (Autumn, 1988), pp. 156-164. What you NEED to know and remember is that the précis is a highly structured four sentence paragraph that records the essential elements of a unit of spoken or written discourse. Each of the four sentences requires specific information. The Rhetorical Précis Format Sentence 1 In a single coherent sentence give the following: – Name of the author, title, date (in parentheses) of the work (immediately after the title), genre, and source; – A rhetorically accurate verb such as “asserts,” “claims”, “suggests”, “argues,” “refutes,” “proves,” or “explains.” – A that clause containing the major claim, thesis statement, of the work. THE WHAT SAMPLE SENTENCE 1 Sheridan Baker, in his essay "Attitudes" (1966), asserts that writers' attitudes toward their subjects, their audiences, and themselves determine to a large extent the quality of their prose. The Rhetorical Précis Format Sentence 2 In a single coherent sentence give an explanation of how the writer develops and supports the major claim (thesis statement). THE HOW SAMPLE SENTENCE 2 Baker supports this assertion by showing examples of how inappropriate attitudes can make writing unclear, pompous, or boring, concluding that a good writer "will be respectful toward his audience, considerate toward his readers, and somehow amiable toward human failings" (58). The Rhetorical Précis Format Sentence 3 In a single coherent sentence give a statement of the author’s purpose, followed by an “in order to” phrase, followed by the explanation of the author’s purpose. THE WHY SAMPLE SENTENCE 3 His purpose is to make his readers aware of the dangers of negative attitudes in order to help them become better writers (55). The Rhetorical Précis Format Sentence 4 In a single coherent sentence give a description of the intended audience and/or the relationship the author establishes with the audience. TO OR FOR WHOM SAMPLE SENTENCE 4 He establishes an informal relationship with his audience of college students who are interested in learning to write "with conviction" (55). The Paragraph Sheridan Baker, in his essay "Attitudes" (1966), asserts that writers' attitudes toward their subjects, their audiences, and themselves determine to a large extent the quality of their prose. Baker supports this assertion by showing examples of how inappropriate attitudes can make writing unclear, pompous, or boring, concluding that a good writer "will be respectful toward his audience, considerate toward his readers, and somehow amiable toward human failings" (58). His purpose is to make his readers aware of the dangers of negative attitudes in order to help them become better writers (55). He establishes an informal relationship with his audience of college students who are interested in learning to write "with conviction" (55). Read “Why Is American Internet So Slow?” by John Aziz Following the Rhetorical Précis format and the “Rhetorical Précis Worksheet” handout, with a partner, create a Précis for “Why Is American Internet So Slow?” article. Do not neglect to use rhetorically accurate verbs and nouns. FROM NON FICTION TO FICTION Read Mark Antony’s Funeral Oration from Julius Caesar by William Shakespeare Create a Rhetorical Précis, based on Mark Antony’s Funeral Oration. Follow closely the four sentence paragraph structure as you go through your creative process. Read and annotate the text closely, and mark the text for information necessary to complete this task. Antony’s Speech https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7X9C55TkUP 8 MARK ANTONY'S FUNERAL ORATION Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears; I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him. The evil that men do lives after them; The good is oft interred with their bones; So let it be with Caesar. The noble Brutus Hath told you Caesar was ambitious: If it were so, it was a grievous fault, And grievously hath Caesar answer'd it. Here, under leave of Brutus and the rest-- For Brutus is an honourable man; So are they all, all honourable men-- Come I to speak in Caesar's funeral. He was my friend, faithful and just to me: But Brutus says he was ambitious; And Brutus is an honourable man. He hath brought many captives home to Rome Whose ransoms did the general coffers fill: Did this in Caesar seem ambitious? When that the poor have cried, Caesar hath wept: Ambition should be made of sterner stuff: Yet Brutus says he was ambitious; And Brutus is an honourable man. You all did see that on the Lupercal I thrice presented him a kingly crown, Which he did thrice refuse: was this ambition? Yet Brutus says he was ambitious; And, sure, he is an honourable man. I speak not to disprove what Brutus spoke, But here I am to speak what I do know. You all did love him once, not without cause: What cause withholds you then, to mourn for him? O judgment! thou art fled to brutish beasts, And men have lost their reason. Bear with me; My heart is in the coffin there with Caesar, And I must pause till it come back to me. SAMPLE SENTENCE 1 . SAMPLE SENTENCE 2 Marc Antony makes his assertion through an increasingly bitter and ironic characterization of Brutus as a “noble man” and by listing Caesar’s many generous acts, concluding with the legacies Caesar left to the Roman people in his will. SAMPLE SENTENCE 3 Antony’s purpose is to incite a riot against the conspirators in order to avenge Caesar’s death and prevent the conspirators from taking control of Rome. SAMPLE SENTENCE 4 Because the audience is emotionally vulnerable and volatile—and is initially sympathetic to Brutus—Marc Antony first pretends to share his audience’s regard for Brutus before turning the crowd against Caesar’s killers. Because the audience is emotionally vulnerable and volatile—and is initially sympathetic to Brutus—Marc Antony first pretends to share his audience’s regard for Brutus before turning the crowd against Caesar’s killers. (PARAGARAPH 1): PRÉCIS AS AN ESSAY PARAGRAPH . Marc Antony makes this assertion through an increasingly bitter and ironic characterization of Brutus as a “noble man” and by listing Caesar’s many generous acts, concluding with the legacies Caesar left to the Roman people in his will . Because the audience is emotionally vulnerable and volatile—and is initially sympathetic to Brutus—Marc Antony first pretends to share his audience’s regard for Brutus before turning the crowd After the Précis… (PARAGRAPH 2) (PARAGRAPH 3) Develop your thesis. Do you agree, disagree, agree with some but disagree with other? Outline your approach (or attack). Support your claims/reasons with information beyond the text of the article. Break Teaching Revision A Key to Good Writing Donald Murray “Lower your standards until you can start writing.” “Writing is rewriting.” “All writers write badly—at first…. Then they rewrite. Revision is not the end of the writing process, but the beginning.” William Zinsser “Rewriting is the essence of writing well—where the game is won or lost.” Classroom Expectations: Language Fast draft… May not be perfect. Come back tomorrow and make it better… Hard work… Writer-based prose Reader-based prose Save the grading for GAME DAY! Getting Comfy with Revision Revision is about making (and shaping/ reshaping) meanings. Revision (RE-visioning, re-seeing) is RETHINKING. Getting Comfy with Revision Revision is usually messy. Revision: Ask the Right Questions… Does my title help my piece? Does it tell too much or too little? Does it intrigue a reader? Is my introduction interesting and effective? Is the introduction “warm up” for me as a writer? What would happen if I began with the next paragraph instead? Two paragraphs later? Revision: Ask the Right Questions… What else does my reader need to know? Have I provided enough information for a reader to follow my ideas? Will a reader be emotionally connected to my piece? Have I included too much? What could I cut out? Revision: Ask the Right Questions… Have I presented my material in the clearest and most effective order for a reader? Am I telling or showing? Can I add dialogue, descriptive detail, facts, statistics, anecdotes to enliven my writing? Is my conclusion logical? Believable? Organic? Four Key Revision Strategies Reordering Substitution Addition Subtraction Randy Koch: Teaching Revision 1. Give things and people the dignity of their own names. 2. Avoid weak helping and linking verbs. Use specific action verbs instead. 3. Use specific, concrete sensory details. 4. Show, don’t tell, particularly by using dialogue. 5. Cut clutter. 6. Vary sentence structure and length. Tools of the Trade Tools of the Trade Practicing Low Stakes Revision In order to revise, writers need to distance themselves from their own words. – The dog ate my homework! (Tsujimoto’s “memory revision”) – Partner revision – A week later: cut and paste WRITER’S WORKSHOP Our Heroes The Mini Lesson The Work The Author’s Chair & Wrap up Until 2:45… INTRODUCTION TO INQUIRY GROUPS Inquiry Groups Topic ideas: Flash drive readings? Areas of interest? – – – – – – Assessment Content Area Literacy Writing on Demand Technology Standards based curriculum Other? Inquiry Groups Please take 5 minutes and write about a few of the issues that you have concerns, questions, or curiosities about in regards to writing and writing instruction in YOUR teaching world. Compare your list with the person next to you. Share out! Inquiry Groups Groups of people with a shared interest. Collaboration in an academic discussion of issues related to writing and writing instruction. Scheduled meeting times to work together. Start by finding 1-2 people you’d like to work with. Inquiry Groups Sign-up for the inquiry (names and topics) in which you wish to participate. No more than 2-3people per group Sharing what you learned Wednesday, 7/23. Inquiry Groups Take a few minutes now and write in your journals about what you hope to gain from this experience. How do you think the topic you’ve chosen can connect to what you do in the classroom? Comments? Concerns? “Inquiries”? For Next Time… Explore the Technology section, paying special attention to the readings listed on the schedule. – What are you learning? – What is interesting? What concerns do you have?