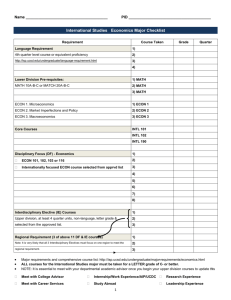

Econ Core

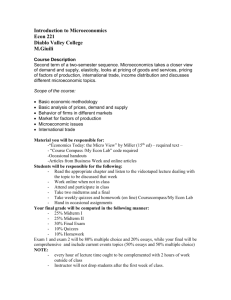

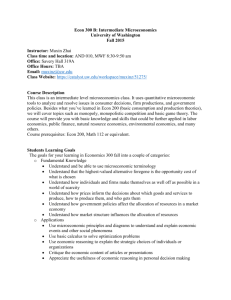

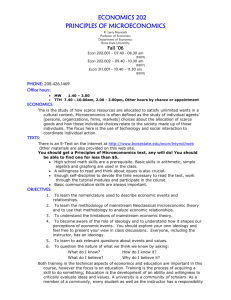

advertisement