mini solo reference material

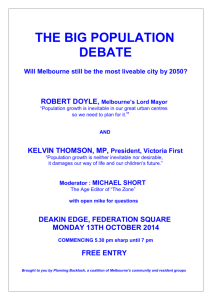

advertisement