Back Pain - Emergency Care Institute

advertisement

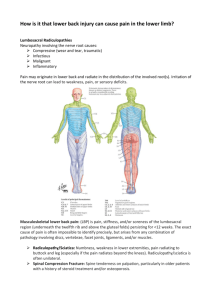

Medical Bites Back Pain ECINSW C I - N S W Back Pain Lecture to go with Medical Bites Back Pain Red Flags for diagnoses not to miss Acute on chronic pain associated with increasing weakness (CES) Weakness or sensory symptoms associated with systemic symptoms, such as fever or nausea, implies an infective cause Neurological symptoms and signs of any kind without a clear explanation Warfarin use and back pain is retroperitoneal haemorrhage until proven otherwise Back Pain Red Flags for diagnoses not to miss A past medical history of cancer associated with new back pain equals malignant metastases until proven otherwise New atrial fibrillation associated with new back pain, especially in as yet anticoagulated patients, equals ischaemia of the spinal cord Back Pain Objectives To be able to assess, diagnose and treat serious and common presentations of back pain To be aware of the risks and red flags associated with back pain Back Pain Definitions Pain described by the patient or clinician as arising from the back. Back Pain Risks Rupture Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm (AAA) Renal colic Pneumonia Retroperitoneal Haemorrhage Remember the Drug seeker, but don’t make it life’s ambition Spine, infection, malignancy and fracture Cauda equina( the major back emergency) Back Pain Recognition of illness Always need to assess for Potential airway compromise Potential respiratory failure Potential circulatory failure Potential neurological failure Vitally important to identify when any patient approaches the end of their ability to compensate for illness or injury Just because a clinical variable is normal does not mean that it still will be in 5 minutes time Back Pain Recognition of illness Clinical signs of potential ABCDE system failure are similar whatever the underlying process These signs reflect failing respiratory, cardiovascular and neurological systems We therefore always need to assess ABCDE to identify failure in one system, AND the effect of failure on other systems If we treat immediately, we prevent further harm Back Pain Immediate actions Global overview of patient Speak to patient Formally examine ABCDE Treat problems in systems - find an airway problem, treat it immediately… Resuscitate - aim to reverse immediate problems and halt deterioration - NOT to aim for normal physiological values Back Pain History – important points Traumatic? Onset and course, is it… Persistent (malignancy, infection) Acute (musculoskeletal) Acute on chronic (pathological) Chronic (degenerative) Urinary / sexual dysfunction Neurological symptoms (cauda equina, nerve route compression) Back Pain History – important points Unexplained fevers (infection) Unexplained weight loss (malignancy) Past back injuries or problems (musculoskeletal) Past medical problems - malignancy, immunocompetency (metastases) Social circumstances (disposition) Back Pain The pain Onset rapid with musculoskeletal slow with infection and malignancy Associations - immediate and delayed Exacerbation musculoskeletal improves with rest or lying still renal colic tends to make you move around relief Back Pain The pain Referral patterns dermatomal patterns remember there are referral patterns with musculoskeletal pathology which is nondermatomal Current analgesia taken, frequency, regularity and doses Back pain Examination Global overview Behaviour Position e.g. lying straight and immobile with musculoskeletal pain Moving around e.g. with renal colic Leaking or ruptured AAA can appear in many guises depending on the extent of the leak but may look very unwell Neurological examination lower limbs Straight leg raise (SLR) - positive test is pain to the foot on extending the straight leg, implies nerve root lesion Back Pain Investigations Often none required, apart from where there is indication from history or examination that there is serious / systemic illness associated with pain Bedside Random blood glucose for diabetes (infection neuropathy risk) ECG for atrial fibrillation (embolic risk leading to spinal ischaemia) Back Pain Investigations Bedside Urinalysis for blood (serious loin pain without haematuria may still be renal colic but AAA must be considered until excluded by ultrasound or CT Laboratory FBC - Hb (anaemia from leaking AAA, malignancy), WCC (infection) EUC - renal function, metabolic disturbances Blood cultures - if febrile Back Pain Investigations Imaging A number of ED physicians / surgeons can do ultrasound scans to investigate for AAA Attempt to organise this investigation rapidly when there is any suspicion of a leaking aneurysm (i.e. any older person with abdominal pain when another convincing diagnosis is not immediately apparent) Back Pain Investigations Imaging Lumbar spine or other X-rays may be helpful, but where there is acute atraumatic or low impact traumatic musculoskeletal pain presenting for the first time in the ambulatory patient, they very rarely are In fact there is little correlation between X-ray findings and pain scores Back Pain Investigations Imaging CT scans are often performed for back pain, but when they are not specifically targeted at investigating serious pathology such as malignancy / metastases or fractures (where mechanism or clinical picture or plain films suggests fracture) they very rarely change management Back Pain Investigations Imaging Minor disc lesions and degenerative changes which do not necessarily correlate with symptoms are often disturbing and misinterpreted by clinicians and patients Consider…. If you are doing a CT scan of the back you are giving a large radiation load Back Pain Investigations Imaging Particularly in young and women patients you must have a clear set of differential diagnoses and treatment plans in mind, depending on your result If you cannot do this then refer on for more senior consultation Back Pain Investigations Imaging MRI may be performed as an emergency investigation where there is suspicion of cauda equina syndrome (the major diagnosis not to miss), in order to diagnose spinal cord compression This is done urgently and often requires a number of phone calls or transport out of regular hours to another facility MRI for other indications is not an emergency Investigation Back Pain Diagnoses not to miss Cauda equina syndrome (CES) - a neurological emergency Fractures of any kind, particularly unstable ones Infections of the spine, often at the extremes of age Inflammatory conditions of the spinal cord Nerve root compressions Blood supply compromise e.g. secondary to AF, emboli Back Pain Red Flags for diagnoses not to miss Acute on chronic pain associated with increasing weakness (CES) Weakness or sensory symptoms associated with systemic symptoms, such as fever or nausea, implies an infective cause Neurological symptoms and signs of any kind without a clear explanation Warfarin use and back pain is retroperitoneal haemorrhage until proven otherwise Back Pain Red Flags for diagnoses not to miss A past medical history of cancer associated with new back pain equals malignant metastases until proven otherwise New atrial fibrillation associated with new back pain, especially in as yet anticoagulated patients, equals ischaemia of the spinal cord Back Pain Specifics Cauda equina syndrome (CES) Infection Nerve root compression Inflammatory and ischaemic Musculoskeletal Fractures Muscular pain Back Pain Specifics Cauda Equina syndrome (CES) Low back pain Unilateral or usually bilateral sciatica Saddle sensory disturbances Bladder and bowel dysfunction Variable lower extremity motor and sensory loss Back Pain CES - pathophysiology Compression of susceptible cauda equina nerve roots May be caused by… Trauma Lumbar disc disease Abscess Spinal anesthesia Back Pain CES - pathophysiology Compression of susceptible cauda equina nerve roots May be caused by… Tumour, either metastatic or CNS primary Late-stage ankylosing spondylitis Idiopathic Inferior vena cava thrombosis Lymphoma or sarcoidosis Back Pain CES - history Low back pain Acute or chronic radiating pain Unilateral or bilateral lower extremity motor and /or sensory abnormality Bowel and / or bladder dysfunction; symptoms may be described within a spectrum from hesitancy to incontinence, which is overflow from an atonic bladder Saddle (perineal) anaesthesia Back Pain CES - examination Local lumbar tenderness to palpation or percussion Reduced reflexes (not increased reflexes which implies an upper motor neurone lesion in the spinal cord) Sensory abnormalities over the perineal area or lower extremities Light touch in the perineal area should be tested Muscle weakness may be present in muscles supplied by affected roots Back Pain CES - examination Muscle wasting may occur if CES is chronic Poor anal sphincter tone is characteristic of CES Babinski sign or other signs of upper motor neuron involvement, suggests a diagnosis other than CES, such as an intrinsic cord lesion or external compression Anaesthetic areas may show skin breakdown A large residual post-void urine as measured by catheterisation Back Pain CES - investigation Bedside Urinalysis for infection Laboratory FBC WCC - investigating for infection Hb - investigating for malignancy Imaging Key investigations are imaging Back Pain CES - investigation Imaging Plain radiography usually not helpful, however may be used to look for destructive lesions, discspace narrowing, or spondylolysis (degeneration of an articulating part of a vertebra) CT with / without contrast - lumbar myelogram followed by CT MRI - currently considered a requirement in suspected CES, but improved CT scanners may disprove this Back Pain CES - treatment If suspect CES consult neurosurgical early for directed investigations and ongoing management Early steroids may be used Surgical decompression may be appropriate, depending on aetiology Depending on local institutional practice surgery may be performed early, intermediate or late Specific treatments such as antibiotics depend on suspected causes Back Pain Infection Pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis is the most commonly encountered form of vertebral infection Aetiology may be from direct open spinal trauma infections in adjacent structures hematogenous spread of bacteria can occur postoperatively Left untreated, it can lead to permanent neurologic deficits, significant spinal deformity, or death Back Pain Infection – risk factors Advanced age Intravenous drug use Congenital immunosuppression Long-term systemic administration of steroids Diabetes mellitus Organ transplantation Malnutrition Cancer Back Pain Infection - history Back pain which is increasing, and lasting for weeks to months Fever is present in around 50% of patients Back Pain Infection - examination Local tenderness, which may be initially mild Neurologic signs are usually late and occur due to bony destruction Decreased range of motion Radicular (nerve root) signs and paralysis suggest epidural abscess Back Pain Infection - examination Sensory examination includes sensory level heat / cold pain reflexes rectal tone perianal sensation Back Pain Infection - investigation Bedside Urinalysis - infection, diabetes, blood Laboratory VBG - metabolic status FBC - WCC as sign of infection Other inflammatory markers are often performed (ESR, CRP) but do not rule in or rule out infection, and are often a waste of time Blood cultures may be of benefit Clinical suspicion mandates further testing with imaging Back Pain Infection - investigation Imaging Plain radiography will show late destructive lesions CT with and without contrast MRI if available and most likely after CT Technetium uptake scans for activity of osteomyelitis Back Pain Infection - treatment Assessment using ABCDE, as infective back pain may represent an underlying systemic sepsis or may lead to this Keep tuberculosis in mind, particularly in at-risk groups Initially broad spectrum antibiotics are used, however consult early and widely, including microbiology Back Pain Infection - treatment Adequate analgesia – often requiring IV opiates The premorbid state which allows spinal infection implies the patient is at risk of numerous pathologies, therefore a full medical workup is required but is likely to occur over time as an in-patient Back Pain Nerve root compression This back pain diagnosis is one of the more clear cut, given that the history refers to both motor and sensory issues in a nerve root distribution, with concurrent reflex abnormalities Key point - signs must fit the nerve root distribution, and there must not be signs or symptoms suggestive of other red flag pathologies, such as infection or cauda equina syndrome The key to nerve root distributions is dermatomal pattern, and which roots are involved in various muscle groups (myotomes) and reflexes Back Pain Nerve root compression - history Pain as initial complaint, then varying degrees of weakness as a later symptom May be history of trauma, and often of chronic back pain Specifically question to elicit symptoms of infection or malignancy, including fevers, weight loss and general malaise Pain medication history is important, to gauge both pain severity and potential for dependence after prolonged use Back Pain Nerve root compression - examination Lower limb for obvious asymmetry of colour and skin texture, to detect other system involvement such as Circulation Full neurological examination of lower limb *(see practical skills) Straight leg raise (SLR), is positive when the leg is elevated with the patient supine and pain radiates to the foot; this implies a nerve root lesion Back Pain Nerve root compression - examination Sensory landmarks C6 at the thumb T4 at the nipple T10 at the umbilicus L5 at the top of the foot S1 over the sole of the foot S2-S4 at the perineum (see dermatome chart) Back Pain Nerve root compression Back Pain Nerve root compression - investigation Bedside Urinalysis - infection, diabetes, blood Laboratory As indicated by history and examination, however none may be indicated Imaging Plain X-rays are usually of no use but be guided by the patient history Back Pain Nerve root compression - investigation Imaging CT scan may be of use but it will confirm nerve root compressive elements MRI may be required Importantly, often none of the above are urgent if no red flags are present Back Pain Nerve root compression - management Early, effective analgesia is the key to treating any back pain IV opiates if needed ‘Triple analgesia’ Paracetamol 1g 6 hourly PO Ibuprofen 400mg 6-8 hourly PO Oxycodone 5mg 6 hourly PO Back Pain Nerve root compression - management Together with analgesia and reassurance, early referral for assessment and specialist management of nerve root symptoms is the mainstay of treatment For significant symptoms such as debilitating weakness, or unrelieved pain, admission may be very rarely required Back Pain Inflammatory and ischaemic These are very important diagnoses and often very difficult to appreciate early the key is to respond to positive findings and indicators in your history and examination by appropriate investigations, and thereafter by referral If you have a positive finding do not ignore it because it does not fit your diagnosis. If it doesn’t fit it may be spurious but it may also be part of a complex presentation; always ask senior ED and refer if possible Back Pain The commonest diagnosis Musculoskeletal mechanical back pain Logically this is divided into… Fractures Muscular pain Back Pain Fractures The diagnosis of fractures starts with suspicion… when there is a mechanism which could transmit significant load to the back, including compressive forces such as a heavy object hitting the top of the head and transmitting energy down the spine Back Pain Fractures - examination Primary survey, ABCDE approach and immediate resuscitation in systems, including oxygen, IV analgesia and fluids via x2 large bore cannulae (see serious trauma lecture) Call for help early - senior ED Thorough top to toe examination (secondary survey) Full neurological examination This will then direct you, given the background level of suspicion to appropriate imaging, remembering Nexus / Canadian C-spine rules Back Pain Fractures - examination Nexus rules If the patient is alert, and there is… No neck pain No posterior midline cervical spine tenderness present No evidence of intoxication present A normal level of alertness No focal neurologic deficit present No painful distracting injury You do not have to image this patient Back Pain Fractures - examination Canadian C-spine rule Patient alert (GCS 15) Not intoxicated No distracting injury (e.g. long bone fracture, large laceration) The patient is not high risk (age >65 years or dangerous mechanism or paraesthesia in extremities) A low risk factor that allows safe assessment of range of motion exists. This includes simple rear end motor vehicle collision, seated position in the ED, ambulation at any time post-trauma, delayed onset of neck pain, and the absence of midline cervical spine tenderness The patient is able to actively rotate their neck 45 degrees left and right Back Pain Fractures - management Any patient in which a spinal fracture is suspected must be kept immobilised and other suspicious areas imaged, i.e. when there is one spinal fracture there is a 10% likelihood of another being present Immobilisation means a C-collar needs to be applied and remain in place, and the patient log rolled when transport or movement required (see practical skills) Back Pain Fractures - management Analgesia, using morphine IV titrated to pain Antiemetics, traditionally metclopramide 10mg, and more recently ondansetron 4 mg IV Steroids may be requested by neurosurgeons managing the patient Back Pain Muscular – introduction A number of both senior and junior doctors dislike seeing back pain patients; this is because of the perceived difficulties in their management As with all our difficult ED patients, when a system is applied it assists the resolution of the patient’s problems, and the dilemma of the clinical staff. The key to adequate treatment of back pain is getting the confidence of the patient early Back Pain Muscular - history Often there is no history of major or even minor trauma, but sudden onset after, for example, ‘bending to pick up a pen’ There is usually back-straining activity in the last two weeks, or there is a history of a backintensive occupation such as bricklayer or mother of young children Red flags, as mentioned earlier, need to be carefully excluded Back Pain Muscular - examination ABCDE Full neurological examination including SLR Full examination looking for other systems pathology as indicated Examination may be normal, but limited due to pain; if this is the case you have given enough analgesia to relieve resting discomfort Back Pain Muscular - investigation None Back Pain Muscular - management Early analgesia, in adequate amounts, is the mainstay of treatment See triple therapy described earlier Ensure you give a clear explanation that the medications in triple analgesia therapy are… …metabolised separately, so no risk of overdose …multiplicative rather than additive, so give added analgesia …taken regularly rather than PRN, to ensure adequate ‘levels of pain relief’ Back Pain Muscular - management Start on full dose triple therapy, and give clear instructions about titrating analgesia down To get the patients confidence you must get their comfort and then you will get cooperation If pain is severe, control initially with morphine and then introduce oral medications early if you intend to discharge the patient (you do!) The principle is the oral medications take over from the morphine and discharge can be facilitated Back Pain Muscular - management If you incrementally increase / escalate pain medications because each one does not work individually, the patient will remain longer in the ED, you will lose their confidence and make discharge harder Therefore - titrate morphine 5 mg + 2.5mg IV…etc until pain relief achieved Depending on amount required after 2 hours add in oral paracetamol 1g and oxycodone (5mg for milder pain, 10mg for more severe) When patient has had some food give some ibuprofen 400mg Back Pain Muscular - management In this way, after 3-4 hours, and even in patients with severe back pain, you may have someone who is able to be discharged For less severe pain, commence with either ibuprofen, paracetamol or oxycodone depending on the level, or potentially a combination of two agents rather than three Ensure, however, that the patient has good analgesia, rather than worry about too much analgesia Discuss ongoing requirements and the pathophysiology of the pain with the patient Back Pain Muscular - management Explain that the severity of the pain often does not reflect the amount of pathology or damage, and that the spasm is a protective mechanism If discharging the patient, you need to know full social circumstances Advise that manipulation should not be done acutely and may not help in the long term, but good advice regarding back management from physiotherapists and osteopaths may Remember a number of patients will attend other clinicians and rather than disregarding this you should advise how best to use them Back Pain Summary Give analgesia in adequate amounts, titrate in a timely fashion Keep red flags in mind, and if the history and examination does not fit then be suspicious Drug seeking is a possibility, but be careful with this as a diagnosis (e.g. IVDUs get spinal infections). It is better to give an opiate addicted person one episode of medication than to deny a person in pain the analgesia they really need We need to engender Comfort, Confidence and Cooperation Back Pain Summary The patient who cannot be discharged due to pain or social circumstances should get admission; but you will need to negotiate local custom whether it is appropriately medical (more common in elderly), orthopaedic or neurosurgical as the admitting team. (They are all wankers anyway!) When referring be sure you have adequately trialed analgesia, have a clear clinical picture and can present the patient concisely to the ED senior or other clinician