Peter the Rabbit

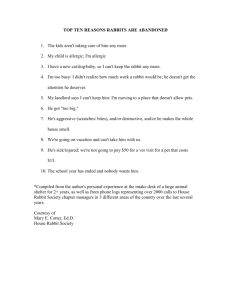

advertisement

Chen i Victoria Chen Mrs. E. Richardson British Literature 12 November 2012 Ironic Rise of a Hero in The Tale of Peter Rabbit Thesis: In her ironic cover up, Potter turns Peter into a hero by subtlety blaming the righteous Mrs. Rabbit for endangering her son, turning the victim of offense, Mr. McGregor, into a villain, and exempting Peter from any serious consequences. I. Mrs. Rabbit’s endangering of her son A. Clothes B. Children’s name II. Turning Mr. McGregor into a villain A. Illustrations vs. narrator B. Mr. Rabbit’s death III. Exempting Peter from any serious consequences A. Clueless Mrs. Rabbit B. Furious Mr. McGregor C. Criticism from readers Chen 1 Victoria Chen Mrs. E. Richardson British Literature 12 November 2012 Ironic Rise of a Hero in The Tale of Peter Rabbit Beatrix Potter’s The Tale of Peter Rabbit is a timeless children’s story that follows the troublesome and gluttonous protagonist, Peter Rabbit, who disobeys his widowed mother, the hardworking Mrs. Rabbit, to trespass into a neighboring garden. Upon entering the garden, Peter indulges in copious amounts of vegetables, making him sick. Peter’s rebellious and hedonistic actions land him in nearly fatal confrontations with Mr. McGregor, the ruthless owner of the garden. Yet, by the grace of Potter, Peter narrowly escapes the same harrowing fate as his father’s in becoming Mrs. McGregor’s rabbit pie. Potter implements humor to exploit Peter’s foolishness and narrates in an objective voice (like that of a parent) to ironically cover up her secret supporting of him while manipulating readers into sympathizing with the naughty rabbit. In her ironic cover up, Potter turns Peter into a hero by subtlety blaming the righteous Mrs. Rabbit for endangering her son, turning the victim of offense, Mr. McGregor, into a villain, and exempting Peter from any serious consequences. Potter hilariously implies that Peter’s foolish fumbles are a product of Mrs. Rabbit’s upbringing. First, Mrs. Rabbit humanizes her son by giving him the name “Peter,” making him wear clothes, and raising him to stand on his hind legs like a human being. His garb, it turns out, nearly gets him killed: his jacket ensnares him in a gooseberry net and his shoes slow him down. In shedding his burdening human characteristic, Peter returns to being the rabbit he really is: “After losing them [shoes], he ran on all four legs and went faster” (Potter 33). Critic Melissa Chen 2 Gross concludes, “It becomes clear that, in order to deal with Mr. McGregor and his predicament, Peter must revert to his natural self and depend on his wilderness to survive.” However, immediately after discarding one burden, Peter is brought down by another; the narrator relates that “unfortunately [he had] run into a gooseberry net, and got caught by the large buttons on his jacket” (35). Likewise, Gross concludes, “The coat also has to go.” Peter’s gradual loss of clothes symbolizes his departing from anthropomorphism. Critic Ruth K. MacDonald asserts: “Peter is no longer a naughty boy, but has reverted to his rabbit nature.” Readers no longer see Peter as a foolish youngster, but see him as a rabbit scrambling for survival. Toward the end of the story, Mr. McGregor collects Peter’s articles of clothing and hangs them on a post as “a scarecrow to frighten the black-birds” (63). Humorously, the accompanying illustration shows that complete opposite: the scarecrow did not actually scare away black-birds but, ironically, attracts a group of them. Even more amusing, critic Carole Scott notices: “Mr. McGregor’s presence nearby [doesn’t] cause any distress.” Perhaps Potter is implying that these “black birds” are crows that are drawn to the scent of death that follows Mrs. Rabbit’s taboo clothes. The absurdity of Mrs. Rabbit’s rearing of her children is further augmented in Potter’s ironic manipulation of names of her characters. For example, Peter possesses the only human name (one of biblical significance) in his rabbit family; therefore, he is expected to be the most sophisticated. Yet, somehow Mrs. Rabbit fails to rear him accordingly. The unbiased narrator reinforces the contrast between Peter and his sisters, depicting his sisters as “good little bunnies” (13), while describing Peter as a “very naughty” (15) rabbit. Humorously enough, the “good little bunnies” have degrading pet names, such as Flopsy, Mopsy, and Cotton-tail. Through this naming, Mrs. Rabbit deteriorates her daughters to the level of a domesticated, household animal. Chen 3 Perhaps this is why Peter’s mundane sisters never defy their mother and are always obedient, “good little bunnies.” Flopsy, Mopsy, and Cotton-tail always appear in groups of three in Potter’s illustrations—when they are picking berries, watching their mother make tea, and eating supper. They’re unable to separate, and therefore, they cannot act independently on their own. While Peter’s sisters’ brain-washed characteristics are a derivative of their pet names, Peter’s name brings unique liveliness that is channeled through his actions. With his human name, Peter automatically has more authority than his sisters. He is also free from the domineering influence of Mrs. Rabbit, who has a half-human-half-animal name, and can act and think independently. Consequently, he possesses the power to disobey direct orders of his mother, which he so commonly does. When Mrs. Rabbit explicitly orders her children to “run along, and don’t get into any mischief” (9), Peter heeds this as a cue to run “straight away to Mr. McGregor’s garden” (13), “the exact thing [his] mother has told them not to do” (Gross). Gross explains, “Here he [Peter] practices his ability to move away from mother and to act autonomously in the world” (3). Again, Mrs. Rabbit’s humanizing of Peter’s contributes to his wanting to adventure into Mr. McGregor’s garden. From this perspective, readers can blame Mrs. Rabbit for her son’s rebelliousness, giving them a reason to tolerate Peter’s irresponsible actions. In addition to vilifying Mrs. Rabbit, Potter refutes the stereotype of the hardworking, deserving, “Neighbor Rosicky” farmer by depicting Mr. McGregor as a ruthless, cane-waving murderer who killed Peter’s father and is out to get the good-for-nothing Peter. To depict Mr. McGregor as a convincing villain, Potter couples the distanced storytelling of her narrator with close and personal illustrations. Critic Eliza T. Dresang asserts, “relationships…exist between words and pictures: they can be in agreement with the text…they can extend the text…or they can contradict the text…Words become pictures and pictures become words.” In this set up, Chen 4 Potter’s pictures bring out more of the story than the objective and almost shallow narration. Scott explains, “the narrative voice is objective, even distanced…and contrasts with the immediacy of the pictures…While the narrative voice of the verbal text may be ambiguous, the illustrations are clear.” The narrator flatly understates Mr. McGregor as harmlessly “intending to pop [a sieve] upon Peter” (39), and Peter as a silly rabbit who “wriggled out” (39) of harm’s way just in time. However, the accompanying picture tells a different story; one of Mr. McGregor’s murderous pursuit and Peter’s narrow escape. Scott states, “seeing the viewpoint of the illustrations so low to the ground and with such constricted vision continually reinforces the sense of peril and the reader’s identification with Peter and his plight.” Through this presentation, Potter “deepens the reader’s involvement in and comprehension of the story” (Scott) by illustrating the victimized Mr. McGregor as a villain, tricking her readers into siding with the rambunctious rabbit. In further degrading Mr. McGregor’s image, Potter reinstitutes likeable human characteristics in Peter (who had recently discarded his “burdening” human characteristics) to create sympathy for the pitiful rabbit. Potter, once again, uses her illustrations to effectively sway her readers. Again, the narrator describes the scene in an unemotional tone, “render[ing] the action low in drama and energy” (Scott). When the narrator says, “Peter began to cry” (51), he offers no supporting adjectives to indicate any form sympathy—resulting in just a cold description of Peter’s predicament. However, Potter’s illustration shows that the naked Peter has returned to standing on his hind legs, using his paws to wipe away a large, very-human tear drop; he returns to his anthropomorphic stature—something he knows well and, perhaps, finds comforting (a link to his mother). Scott elucidates the illustration’s effect: “When Peter begins to cry, his human childlikeness speaks strongly to the reader because the illustration and Chen 5 the verbal text work in harmony to present his hopelessness and fearful exhaustion.” As if this weren’t powerful enough, Potter introduces an old mouse, a symbol of hope and direction, who chooses to crush Peter by not answering him when he asks her for help. Unfortunately, “she had such a large pea in her mouth that she could not answer” (51). The old mouse’s uselessness augments the sense of hopelessness that surrounds Peter. This scene pulls at the heartstrings of readers. After all, it is very difficult not to feel sorry for a lost, whimpering rabbit—no matter how naughty he is. Thus, Scott declares, “I am not alone in my judgment that the sympathies of Potter, and thus the reader, are with Peter.” For once, Mrs. Rabbit is not to blame; all fingers point to Mr. McGregor. Potter also exploits the themes of death. Dresang notes, “Death… [is] avoided by many authors.” However, unlike most authors of children’s books, Potter strategically manipulates the controversial theme of death to her advantage, managing to make her story appropriate for her young audience while effectively evoking sympathy for the mischievous. Critic Richard Carlson proposes, “Beatrix Potter… [is] what he calls a “benign humorist”…Potter’s stories have a “teardrop at the center of each laugh” (qtd. in Nilsen 54). Potter implements Mr. Rabbit’s death to play with human emotions and forces readers to view Peter, the naughty and gluttonous troublemaker, in a new light. Readers are compelled to justify Peter’s juvenile behavior as a rightful act of avenging his father. With the backing of his father’s death, Peter is transformed into both “an unusual hero” (Scott) and “A Rebel with a Cause” (Dresang). Additionally, Mr. McGregor sings tunes of death: “someone [Mr. McGregor (the only other person in the garden)] began to sing ‘Three blind mice, three blind mice!’… made him [Peter] feel as though his own tail were going to be cut off; his fur stood on end” (57). Clearly, this is an “ominous indication of the farmer’s attitude toward stray animals” (MacDonald). In addition to charging Mr. McGregor Chen 6 with the murder of Mr. Rabbit, Potter subtly throws in her own prejudice, recognizable by a fellow Britain. The surname McGregor is Scottish; in making Mr. McGregor Scottish, Potter takes advantage of the longstanding resentment between the Ireland and Britain to vilify Mr. McGregor. Obviously, Potter despises Mr. McGregor and wants her readers to too. Mr. McGregor’s bloody history of barbarically killing and eating Mr. Rabbit is what “seals the deal” in his being portrayed as a villain and accordingly, Peter’s glorification. Lastly, Potter exempts Peter from any serious consequences, enforcing the mindset that Peter is guiltless in—even entitled to—trespassing into Mr. McGregor’s vegetable garden. Critic Scott recognizes this: “Although Peter disobeys his mother and causes her anxiety and grief, commit trespass and theft…nonetheless he escapes all punishment for his misdeeds, except for a temporary stomachache resulting from his greediness.” Unlike his father, Peter escapes Mr. McGregor’s labyrinth of cabbages and radishes. Potter tries very hard to convince readers with her narrator’s objectiveness that Peter’s narrow escapes are a result of coincidence and luck—not her preference. During his time in Mr. McGregor’s garden, Peter manages to untangle from the dooming gooseberry net and outrun Mr. McGregor, despite being “fat little rabbit” (49). Miraculously, halfway through his pursuit of Peter, Mr. McGregor, the murderous farmer, gives up. In escaping the terrifying Mr. McGregor, Peter becomes a hero. Peter also escapes his Mother’s chastisement. When Peter finally returns home under the fir tree, he is so tired that he collapses on the floor. Yet, Mrs. Rabbit’s only concerns are the whereabouts of Peter’s clothing: “she wondered what he had done with his clothes. It was the second jacket and pair of shoes that Peter had lost in a fortnight!” (67). Peter’s only remaining punishment can come from his losing his clothes, and at the most, that would result in a light pat on his furry buttocks. Yet, Mrs. Rabbit assumes Peter’s symptoms of fatigue are a product of Chen 7 strenuous blackberry picking. Entertainingly enough, the distanced narrator also seems to totally misinterpret Peter’s ailment as a “consequence of having eaten too much in Mr. McGregor’s garden” (75)—rather than the resulting physical and mental stress the fat rabbit experiences from escaping the garden—even though the narrator was with Peter from the beginning of his fumbles. Consequently, Peter will spend a few days naked. However, this means he will be free of any anthropomorphic hindrance and free to be the true rabbit he really is! If anything, the loss of clothes does not punish Peter; it punishes Mrs. Rabbit, his oppressive mother who now must work even harder to buy him new clothes: “It [Peter’s losing of his clothes] was really most provoking for Peter’s mother, because she had not very much money to spend upon new clothes” (69). Ironically, the narrator describes Mrs. Rabbit as “provoked” by the loss of clothes; yet, she does nothing to punish Peter. At the end of the day, Peter escapes his mother’s wrath and is put to bed with chamomile tea. Everything that could go wrong—death by gooseberry net, parental censure—doesn’t; Potter makes sure of it for her little hero. Peter even escapes consequences outside the bounds of his story; he manages to escapes the condemnation of his rational readers—with the help of Potter. Potter craftily sways readers against Mr. McGregor while using “a narrative voice [that] sometimes takes an adult judgmental tone” (Scott) as a façade to establish a superficial moral and satisfy adult readers. Referencing another critic in decoding Potter’s narrator, Margaret Mackey suggests, “On the surface, she [Potter] is clearly on the side of law and order…But the detached tone with which Potter describes Peter’s disobedience actually functions to raise the question of just whose side she is on” (qtd. in Scott). No matter how detached and objective the voice of narrator is, the fact that Peter ironically escapes all forms of punishment reflects whom Potter truly supports: Peter. Alison Lurie asserts, “Consciously or not, children know that the author’s sympathy and interest Chen 8 are with Peter…not with the obedient, dull little Flopsy, Mopsy, and Cottontail” (qtd. in Nilsen 54). Like this, Potter manipulates generations of families into supporting the fat, little rabbit. In The Tale of Peter Rabbit, Potter ultimately makes readers side with Peter, the juvenile rabbit by blaming his hardworking mother, vilifying Mr. McGregor, and excusing Peter from grim consequences. Potter exposes the worst of Mrs. Rabbit when she ironically blames the hardworking, single-mother. Potter is most critical of Mrs. Rabbit’s inconsistent, unfair rearing of her children. She picks favorites, giving Peter (it is appropriate to ascertain that he reminds Mrs. Rabbit of her husband) the most clothes and a human name (the most freedom) while giving his sisters almost no clothes and humiliating pet names (stripping them of their independence and free will). Although Mrs. Rabbit spoils Peter with a “blue jacket with brass buttons” (35), she paradoxically jeopardizes her favorite child’s life. Both Peter’s shoes and jacket prove to be determents to his natural agility when he is running away from Mr. McGregor. The clothes Mrs. Rabbit gives to Peter symbolizes her unnatural humanizing of her son. Potter also turns the laboring Mr. McGregor into a nasty criminal by blaming him for Mr. Rabbit’s death. She harmonizes her impartial narrator with her comprehensive illustrations to throw readers intimately close with Peter during his peril. By blaming Mr. McGregor with Peter’s father’s death and the ancestry of Ireland, Potter prejudicially stamps the owner of the garden with a history of a bloody felony. When Mr. McGregor’s wrong doings are contrasted with those of Peter, readers easily are persuaded to accept the mischievous Peter as an exceptional hero. In her final attempt to sway her readers into supporting Peter, Potter exempts Peter from all penalties the crimes he has committed. In this ironic cover up, Peter, the plump, problematic rabbit that has caused so much damage to his mother’s purse and Mr. McGregor’s vegetables, is Chen 9 exalted to the status of a hero by the hidden support of the author and the undying support of his readers. Chen 10 Works Cited Dresang, Eliza T. "Radical Qualities of The Tale of Peter Rabbit." Beatrix Potter's Peter Rabbit: A Children's Classic at 100. Ed. Margaret Mackey. Lanham, Md.: The Children's Literature Association and The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2002. 99-116. Rpt. in Children's Literature Review. Ed. Jelena Krstovic. Vol. 165. Detroit: Gale, 2011. Literature Resource Center. Web. 13 Sep. 2012. Gross, Melissa. "Why Children Come Back: The Tale of Peter Rabbit and Where the Wild Things Are." Beatrix Potter's "Peter Rabbit": A Children's Classic at 100. Ed. Margaret Mackey. Lanham, Md.: Children's Literature Association and The Scarecrow Press, Inc, 2002. 145-158. Rpt. inChildren's Literature Review. Ed. Tom Burns. Vol. 131. Detroit: Gale, 2008. Literature Resource Center. Web. 14 Sep. 2012. MacDonald, Ruth K. "Why This Is Still 1893: The Tale of Peter Rabbit and Beatrix Potter's Manipulations of Time into Timelessness." Children's Literature Association Quarterly 10.4 (Winter 1986): 185-187. Rpt. in Children's Literature Review. Ed. Jelena Krstovic. Vol. 165. Detroit: Gale, 2011. Literature Resource Center. Web. 13 Sep. 2012. Nilsen, Don L. F. Humor in Twentieth Century British Literature. Connecticut: Greenwood, 2000. Print. Potter, Beatrix. The Tales of Peter Rabbit. Digital Library Services Dept. of The Univ. of Iowa Libraries. Web. 11 November 2012. Scott, Carole. "An Unusual Hero: Perspective and Point of View in The Tale of Peter Rabbit." Beatrix Potter's Peter Rabbit: A Children's Classic at 100. Ed. Margaret Mackey. Lanham, Md.: The Children's Literature Association and The Scarecrow Press, Chen 11 Inc., 2002. 19-30. Rpt. in Children's Literature Review. Ed. Jelena Krstovic. Vol. 165. Detroit: Gale, 2011. Literature Resource Center. Web. 6 Sep. 2012.