Principles of Economics, Case/Fair/Oster, 11e

advertisement

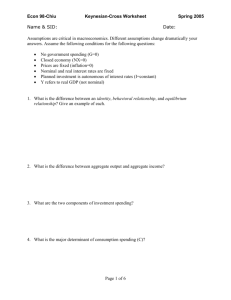

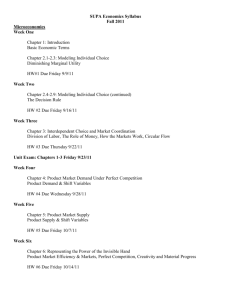

Chapter 8 Aggregate Expenditure and Equilibrium Output The Keynesian Theory of Consumption Determinants of Consumption Planned Investment (I) versus Actual Investment Planned Investment and the Interest Rate (r) Other Determinants of Planned Investment The Determination of Equilibrium Output (Income) The Saving/Investment Approach to Equilibrium Adjustment to Equilibrium The Multiplier The Multiplier Equation The Size of the Multiplier in the Real World Appendix: Deriving the Multiplier Algebraically AGGREGATE OUTPUT AND AGGREGATE INCOME (Y) aggregate output The total quantity of goods and services produced in an economy in a given period. aggregate income The total income received by all factors of production in a given period. In any given period, there is an exact equality between aggregate output (production) and aggregate income. You should be reminded of this fact whenever you encounter the combined term aggregate output (income) (Y). aggregate output (income) (Y) A combined term used to remind you of the exact equality between aggregate output and aggregate income. Important to Note: • Chapters 8 – presents the basic Keynesian macroeconomic model. There is no government in this initial presentation. Government is added in Chapter 9 • The Keynesian model assumes that producers meet demand at preset prices – prices are assumed to be fixed. • All of the adjustment is quantity • The shortcoming of their assumption is that it does not explain changes in prices and inflation. Another Important Note: Think in Real Terms •When we talk about output (Y), we mean real output (real GDP), not nominal output (P x Y). •The main point is to think of Y as being in real terms - the quantities of goods and services produced, not the dollars circulating in the economy. The Business Cycles – Why do They Occur? Log-run trend in potential GDP Boom Slump •Over time, real GDP fluctuates around an overall upward trend. Such fluctuations are called business cycles. When output rises, we are in the expansion phase of the cycle; when output falls, we are in a recession. Unemployment Rate : 1950 - July 2015 July 2015: 5.3% In this last recession: Number of people unemployed increased from 7 million to 14 million Are Recessions Caused by Declining Labor Demand? Real Wage Rate Labor Supply E $25 F 20 90 Million Normal Labor Demand Recession Labor Demand? 100 Million Employment In theory, a recession could be caused by a sudden leftward shift in the labor demand curve, causing employment to fall. But with flexible wages, the labor market clears, so there would be no rise in unemployment, contradicting the facts of actual recessions. Sticky Wages and Leftward Shift in Labor Demand – With sticky or rigid wages, the real wage remains unchanged as labor demand shifts to the left. – you get unemployment ! – this seems to fit what happens in realworld recessions A Recession Caused by Declining Labor Demand - Wage rate rigid at $25 Real Wage Rate Labor Supply H E $25 20 F 80 Million 90 Million Normal Labor Demand Recession Labor Demand? 100 Million What is the level of unemployment in this graph? How many people want to work in this graph? Employment Downward wage rigidity prevents the labor market from clearing. This could, in theory, explain the rise in unemployment during a recession. Are Wages Rigid and WHY? • They seem to be • Institutional factors such as unions and minimum wage. • Employers are hesitant to lower wages negative effect on worker morale and productivity 10 Decrease in Total Spending – Total spending plays an important role in real-world economic fluctuations – Once we step away from the classical model and the assumption that all wages are flexible and markets clear, a combination of a sudden drop in total spending combined with wage rigidity can explain economic fluctuations 11 Short-Run Macro Model • Macroeconomic model that explains how changes in spending can affect real GDP in the short run. • Components of Spending: C, I, G, EX and IM. • Short-run is month-to-month, quarter-to quarter, year-to-year. – Long-run model discussed later covers multi-year time frame – 10-15 years. 12 Start with Consumption Spending (C) • Recall that C (household consumption) is about 70% of total spending on final goods and services. • Consumption spending increases when: – Income (Y) rises – Wealth (W) rises – The interest rate (r) falls – Households become more optimistic about the future - positive expectations about the future 13 The Keynesian Theory of Consumption For consumption as a whole, as well as for consumption of most specific categories of goods and services, consumption rises with income. While Keynes recognized that many factors, including wealth and interest rates, play a role in determining consumption levels in the economy. In his classic The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, current income (Y) played the key role. Quarterly U.S. Consumption and Income, 2000–2014 11000.0 C = 453.95 +0.8713(Y) 10500.0 R² = 0.9783 10000.0 9500.0 9000.0 8500.0 8000.0 8500.0 9000.0 9500.0 10000.0 10500.0 11000.0 11500.0 12000.0 Consumption function The relationship between consumption and income. FIGURE 8.1 A Consumption Function for a Household A consumption function for an individual household shows the level of consumption at each level of household income. With a straight line consumption curve, we can use the following equation to describe the curve: C = a + bY FIGURE 8.2 An Aggregate Consumption Function The aggregate consumption function shows the level of aggregate consumption at each level of aggregate income. The upward slope indicates that higher levels of income lead to higher levels of consumption spending. marginal propensity to consume (MPC) That fraction of a change in income that is consumed, or spent. marginal propensity to consume slope of consumption function C Y aggregate saving (S) The part of aggregate income that is not consumed. S≡Y–C The triple equal sign means that this equation is an identity, or something that is always true by definition. identity Something that is always true. INCOME, CONSUMPTION, AND SAVING (Y, C, AND S) Saving ≡ Aggregate Income − Consumption marginal propensity to save (MPS) That fraction of a change in income that is saved. MPC + MPS ≡ 1 Because the MPC and the MPS are important concepts, it may help to review their definitions. The marginal propensity to consume (MPC) is the fraction of an increase in income that is consumed (or the fraction of a decrease in income that comes out of consumption). The marginal propensity to save (MPS) is the fraction of an increase in income that is saved (or the fraction of a decrease in income that comes out of saving). FIGURE 8.3 The Aggregate Consumption Function Derived from the Equation C = 100 + .75Y In this simple consumption function, consumption is 100 at an income of zero. As income rises, so does consumption. For every 100 increase in income, consumption rises by 75. The slope of the line is .75. Aggregate Income, Y Aggregate Consumption, C 0 100 100 175 200 250 400 400 600 550 800 700 1,000 850 Exercise C = 100 +.90Y AGGREGATE INCOME, Y (BILLIONS OF DOLLARS) 0 100 200 400 600 800 1,000 AGGREGATE CONSUMPTION, C (BILLIONS OF DOLLARS) Deriving the Saving Function from the Consumption Function in Figure 8.3 Because S ≡ Y – C, it is easy to derive the saving function from the consumption function. A 45° line drawn from the origin can be used as a convenient tool to compare consumption and income graphically. At Y = 200, consumption is 250. The 45° line shows us that consumption is larger than income by 50. Thus, S ≡ Y – C = 50. At Y = 800, consumption is less than income by 100. Thus, S = 100 when Y = 800. Y C = S AGGREGATE AGGREGATE AGGREGATE INCOME CONSUMPTION SAVING 0 100 -100 100 175 -75 200 250 -50 400 400 0 600 550 50 800 700 100 1,000 850 150 Exercise C = 100 + .75 Y S=Y - C S=? Other Determinants of Consumption The assumption that consumption depends only on income is obviously a simplification. In practice, the decisions of households on how much to consume in a given period are also affected by their wealth, by the interest rate, their expectations of the future, and taxes • Households with higher wealth are likely to spend more, other things being equal, than households with less wealth. • Lower interest rates are likely to stimulate spending. • If households are optimistic and expect to do better in the future, they may spend more at present than if they think the future will be bleak. Factors that Shift the Consumption Function Upward • an increase in household wealth (W) • a decrease in interest rates (r) • households become more optimistic about the future ( ) • reduction in taxes (T) 26 Upward Shift in the Consumption Function Real Consumption Spending ($ Billions) 6,000 W↑, r ↓, T ↓ , 5,000 4,000 3,000 Consumption Function 2,000 1,000 1,000 2,000 3,000 4,000 5,000 6,000 7,000 8,000 9,000 Real income ($ billions) 27 Factors that Shift the Consumption Function Downward • a decrease in household wealth (W) • an increase in interest rates (r) • household became more pessimistic about the future ( ) • increase in taxes (T) 28 Downward Shift in the Consumption Function Real Consumption Spending ($ Billions) 6,000 5,000 4,000 3,000 Consumption Function W ↓, r ↑, T ↑, 2,000 1,000 1,000 2,000 3,000 4,000 5,000 6,000 7,000 8,000 9,000 Real income ($ billions) 29 Movement Along Versus a Shift • Move along the consumption function – is caused by a change in income • Shift of the consumption function – is caused by a change in factors beside income that cause consumption spending to change (W, T, r, expectations) 30 Planned Investment (I) versus Actual Investment A firm’s inventory is the stock of goods that it has awaiting sale. planned investment (I) Those additions to capital stock and inventory that are planned by firms. actual investment The actual amount of investment that takes place; it includes items such as unplanned changes in inventories. If a firm overestimates how much it will sell in a period, it will end up with more in inventory than it planned to have. We will use I to refer to planned investment, not necessarily actual investment. Planned Investment and the Interest Rate (r) Increasing the interest rate, ceteris paribus, is likely to reduce the level of planned investment spending. When the interest rate falls, it becomes less costly to borrow and more investment projects are likely to be undertaken. FIGURE 8.5 Planned Investment Schedule Planned investment spending is a negative function of the interest rate. An increase in the interest rate from 3 percent to 6 percent reduces planned investment from I0 to I1. Other Determinants of Planned Investment The decision of a firm on how much to invest depends on, among other things, its expectation of future sales. The optimism or pessimism of entrepreneurs about the future course of the economy can have an important effect on current planned investment. Keynes used the phrase animal spirits to describe the feelings of entrepreneurs. For now, we will assume that planned investment simply depends on the interest rate. Keep in Mind aggregate output The total quantity of goods and services produced (or supplied) in an economy in a given period. aggregate income The total income received by all factors of production in a given period. In any given period, there is an exact equality between aggregate output (production) and aggregate income. aggregate output (income) (Y) A combined term used to remind you of the exact equality between aggregate output and aggregate income. Output = Income From the outset, you must think in “real terms.” Output Y refers to the quantities of goods and services produced, not the dollars circulating in the economy. Also, we are taking as fixed for purposes of this chapter and the next the interest rate (r) and the overall price level (P). The Determination of Equilibrium Output (Income) equilibrium Occurs when there is no tendency for change. In the macroeconomic goods market, equilibrium occurs when planned aggregate expenditure (AE) is equal to aggregate output (Y). planned aggregate expenditure (AE) The total amount the economy plans to spend in a given period. Without G, EX and IM, AE is equal to consumption plus planned investment: AE ≡ C + I. Equilibrium: Y = C + I Aggregate output = planned aggregate expenditure Y>C+I aggregate output > planned aggregate expenditure C+I>Y planned aggregate expenditure > aggregate output TABLE 8.1 Deriving the Planned Aggregate Expenditure Schedule and Finding Equilibrium. The Figures in Column 2 Are Based on the Equation C = 100 + .75Y. (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) Planned Unplanned Aggregate Aggregate Inventory Output Aggregate Planned Expenditure (AE) Change Equilibrium? (Income) (Y) Consumption (C) Investment (I) C+I (Y = AE?) Y (C + I) 100 175 25 200 100 No 200 250 25 275 75 No 400 400 25 425 25 No 500 475 25 500 0 Yes 600 550 25 575 + 25 No 800 700 25 725 + 75 No 1,000 850 25 875 + 125 No The 45o Line •A 45° line = translator line •It allows us to measure any horizontal distance as a vertical distance instead Using a 45° Line to Translate Distances A Dollars 1. Using a 45° line . . . Consumption Function 3. into an equal vertical distance (BA). 45° 0 B 2. we can translate any horizontal distance (such as 0B) . . . Dollars Figure 8.6 The Determination of Equilibrium Output (Income) Planned Aggregate Expenditure 45° Output exceeds spending. Unplanned rise in inventories 800 725 E AE=C+I Along the 45° line, income = expenditure 500 Equilibrium Y=C+I 275 200 Spending exceeds output. Unplanned fall in inventories 0 200 500 800 Aggregate Output, Y 39 The Mechanics of Income Determination • If Expenditure line is above 45° line • Total spending > Total output • Production is below equilibrium • Inventories fall so firms increase production • If Expenditure line is below 45° line • Total spending < Total output • Production is above equilibrium • Inventories rise and firms cut back production 40 The Equilibrium Level of Output (Income) Algebraically. There is only one value of Y for which this statement is true, and we can find it by rearranging terms: The equilibrium level of output is 500, as shown in Table 8.1 and Figure 8.6. The Saving/Investment Approach to Equilibrium Because aggregate income must be saved or spent, by definition, Y ≡ C + S, which is an identity. The equilibrium condition is Y = C + I, but this is not an identity because it does not hold when we are out of equilibrium. By substituting C + S for Y in the equilibrium condition, we can write: C+S=C+I Because we can subtract C from both sides of this equation, we are left with: S=I Thus, only when planned investment equals saving will there be equilibrium. FIGURE 8.7 The S = I Approach to Equilibrium Aggregate output is equal to planned aggregate expenditure only when saving equals planned investment (S = I). Saving and planned investment are equal at Y = 500. Adjustment to Equilibrium If AE > Y, planned spending is greater than output, there will be unplanned inventory reductions. Firms respond by increasing output. If AE< Y, planned spending is less than output, there will be unplanned increases in inventories. Firms will respond by reducing output. As output falls, income falls, consumption falls, and so on, until equilibrium is restored, with Y lower than before. As Figure 8.6 shows, at any level of output above Y = 500, such as Y = 800, output will fall until it reaches equilibrium at Y = 500, and at any level of output below Y = 500, such as Y = 200, output will rise until it reaches equilibrium at Y = 500. The Multiplier multiplier The ratio of the change in the equilibrium level of output to a change in some exogenous variable. exogenous variable A variable that is assumed not to depend on the state of the economy—that is, it does not change when the economy changes. The size of the multiplier depends on the slope of the planned aggregate expenditure line: C+I. The steeper the slope of this line, the greater the change in output for a given change in investment. Question: what determines the slope of the AE line? Multiplier Analysis • 45 Multiplier Process – What Happens When Things Change? • What happens if investment (I) increases by $25 – $25 increase investment expenditure, I↑ – creates $25 additional income, Y↑ – MPC ˣ $25 = additional consumption spending, C↑ – creates MPC ˣ $25 additional income, Y↑ – ……… – ……… • Equilibrium GDP rises by a multiple of $25 46 At point A, the economy is in equilibrium at Y = 500. When I increases by 25, planned aggregate expenditure is initially greater than aggregate output. As output rises in response, additional consumption is generated, pushing equilibrium output up by a multiple of the initial increase in I. The new equilibrium is found at point B, where Y = 600. Equilibrium output has increased by 100 (600 500), or four times the amount of the increase in planned investment. Multiplier Analysis • 48 The Multiplier Spending Chain: MPC = 0.75 and Δ Spending = $1,000,000 49 Figure 11 How the Multiplier Builds 50 Multiplier Analysis • In last example each round of spending was 0.75 of previous spending • 1 + 0.75 + (0.75)2 + (0.75)3 • 1 + R + R2 + R3 = 1/(1 – R) • Multiplier = 1/(1 – 0.75) = 4 • In general • 1 + MPC + MPC2 + MPC3 • 1 Multiplier 1 MPC 51 Multiplier Analysis • 1 Multiplier 1 MPC • This formula is oversimplified! • MPC = 0.90, which would imply a multiplier = 10 • In reality, multiplier ≈2 (average of estimates) • We will explain later 52 Multiplier is a General Concept • Any increase in spending can set off the multiplier chain • Autonomous increase in consumption • An increase in consumer spending without any increase in consumer incomes • Shift of the entire consumption function 53 EC ON OMIC S IN PRACTICE The Paradox of Thrift An interesting paradox can arise when households attempt to increase their saving. An increase in planned saving from S0 to S1 causes equilibrium output to decrease from 500 to 300. The decreased consumption that accompanies increased saving leads to a contraction of the economy and to a reduction of income. But at the new equilibrium, saving is the same as it was at the initial equilibrium. Increased efforts to save have caused a drop in income but no overall change in saving. THINKING PRACTICALLY 1. Draw a consumption function corresponding to S0 and S1 and describe what is happening. The Size of the Multiplier in the Real World In considering the size of the multiplier, it is important to realize that the multiplier we derived in this chapter is based on a very simplified picture of the economy. First, we have assumed that planned investment is exogenous. Second, we have thus far ignored the role of government, financial markets, and the rest of the world in the macroeconomy. The size of the multiplier is reduced when tax payments depend on income (as they do in the real world); when we consider Fed behavior regarding the interest rate; when we add the price level to the analysis; and when imports are introduced. In reality, the size of the multiplier is about 2. That is, a sustained increase in exogenous spending of $10 billion into the U.S. economy can be expected to raise real GDP over time by about $20 billion. Looking Ahead In this chapter, we took the first step toward understanding how the economy works. We assumed that consumption depends on income, that planned investment is fixed, and that there is equilibrium. We discussed how the economy might adjust back to equilibrium when it is out of equilibrium. We also discussed the effects on equilibrium output from a change in planned investment and derived the multiplier. In the next chapter, we retain these assumptions and add the government to the economy. REVIEW TERMS AND CONCEPTS actual investment multiplier aggregate income planned aggregate expenditure (AE) aggregate output planned investment (I) aggregate output (income) (Y) aggregate saving (S) consumption function equilibrium exogenous variable identity marginal propensity to consume (MPC) marginal propensity to save (MPS) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. S≡Y−C MPC slope of consumption function MPC + MPS ≡ 1 AE ≡ C + I Equilibrium condition: Y = AE or Y=C+I 6. Saving/investment approach to equilibrium: S = I 7. Multiplier 1 1 MPS 1 - MPC C Y CHAPTER 8 APPENDIX Deriving the Multiplier Algebraically Now look carefully at this expression and think about increasing I by some amount, ΔI, with a held constant. If I increases by ΔI, income will increase by The multiplier is Finally, because MPS + MPC = 1, MPS is equal to 1 - MPC, making the alternative expression for the multiplier 1/MPS, just as we saw in this chapter.