Definition and terminology

advertisement

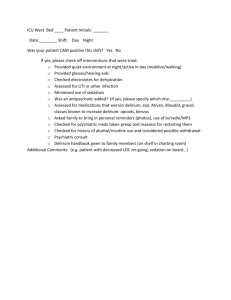

Section of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation presents GRAND ROUND 5/13/2005 by Anthony Tam Pham, DO Case Report Ms. A, a 74-year old white woman who was diagnosed w late-onset bipolar affective disorder at the age of 69, came to the hospital after sustaining a R hip fracture from fall. In the emergency room, she was alert and fully oriented. She received 4 mg of IV morphine sulfate for pain. She slept well and answered questions appropriately the next morning but was drowsy. After hip arthroplasty the following day, she was awake but verbally unresponsive. The next day, she continued to exhibit a blank expression, lethargy, and minimal verbal responses. Rehab was consulted for 9G placement for post-op rehab. At the consultation, she displayed a fluctuating level of consciousness, was disoriented to place and time, had poor attention, uttered only a few words and short phrases, but was pleasant. She did not report feeling depressed, manic, or anxious. Her score on the Mini Mental State Examination was 10 out of 30. Her performance on the clockdrawing task was poor. PMH: HTN, DM, bipolar disorder, CHF no history of stroke, dementia PSH: just hip arthroplasty All: none Med: Lopressor, Glucotrol, lithium, ASA, Lovenox, Percocet prn, dulcolax. Her psychiatrist recommended obtaining an EEG and Head CT. Results showed diffuse slowing and mild small vessel ischemic changes, respectively. EEG findings supported the diagnosis of delirium, and Ms A was given donepezil, 5 mg/day. The next day, she was better but still confused and sleepy. The second day, she was alert and conversant, and displayed some insight. The following day, she was alert, fully oriented, displayed good eye contact and normal psychomotor activity. MMSE was 20/30. She was then transferred to 9G for post-op rehab. DELIRIUM: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment Definition and terminology DSM –IV 1. Disturbance of consciousness with reduced ability to focus, sustain, or shift attention. 2. not better accounted for by a preexisting, established, or evolving dementia. 3. Over a short period of time (usually hours to days), fluctuating during the course of the day 4. Evidence that it is caused by a medical condition, substance intoxication, or medication side effect. Additional features Psychomotor behavioral disturbances such as hypoactivity, hyperactivity w increased sympathetic activity, impairment in sleep duration and architecture Variable emotional disturbances, such as fear, depression, euphoria, or perplexity. Epidemiology of delirium 30% - older medical patients 10-50% - older surgical patients 70% - ICU 42% - Hospice units 16% - postacute care settings Delirium patients experience prolonged hospitalizations, functional decline, high risk for institutionalization. Pathogenesis of delirium Poorly understood Difficult to study severely ill patients Hard to separate from that of underlying illness and drug treatment Pathogenesis: 1.Neurobiology of attention Arousal and attention are governed by: the ascending reticular activating system The “nondominant” parietal and frontal lobes Intact higher order integrated cortical function Pathogenesis: 2. Neurotransmitter 1. Acetylcholine Cause delirium when given to healthy person More likely to lead to confusion in frailty elderly Effects reversed with cholinesterase inhibitors (physostigmine). Medical conditions precipitating delirium, such as hypoxia, hypoglycemia, thiamine deficiency, decrease acetylcholine synthesis in CNS Alzheimer’s disease, characterized by a loss of cholinergic neurons, increases risk of delirium due to anticholinergic medications. neurotransmitters 2. Alterations in neuropeptides (eg, somatostatin), endorphins, serotonin, norepinephrine, and GABA 3. Cytokines, such as interleukins and interferons Pathogenesis: (3) risk factors Multifactorial Underlying brain diseases, such as dementia, stroke, Parkinson’s disease Advanced age and sensory impairment Pathogenesis: (4) precipitating factors Polypharmacy (particularly psychoactive drugs) Infections Dehydration Immobility (including restraint use) Malnutrition The use of bladder catheters Clinical presentation of delirium 1. Disturbance of consciousness A change in the level of awareness and the ability to focus, sustain, or shift attention. – – Often subtle, may precede by one day or more. Patient “isn’t acting quite right” Distractibility, often evident in conversation. Appearing drowsy, lethargic, or even semi-comatose in advanced cases. 2. Change in cognition Cognitive problems: memory loss, disorientation, difficulty with language and speech. – Need to ascertain baseline. Perceptual problems: misidentify the clinician, vague delusions of harm. – Visual and tactile hallucinations are uncommon 3. Temporal course Develop over hours to days and typically persist for days to months Acuteness of presentation is the most helpful feature in differentiating from dementia. Fluctuating: typically most severe in the evening and at night, and relatively lucid during morning. 4. Other features Not essential diagnostic but common, including psychomotor agitation, sleepwake reversals, irritability, anxiety, emotional lability, and hypersensitivity to lights and sounds. Common among older patients includes relatively quiet, withdrawn state that frequently is mistaken for depression. Evaluation of delirium (1) Two important aspects to the diagnostic evaluation: recognizing that the disorder is present, and uncovering the underlying cause. In some reports, clinicians fail to recognize delirium in 70 percent of cases. Wrongly attributed to the patient’s age, to dementia, or to other mental disorders such as depression. Must not “normalize” lethargy or somnolence by assuming that illness, sleep loss, fatigue, or anxiety cause the change. Require knowledge of the patient’s baseline level of functioning. Evaluation (2): Confusion Assessment Method (CAM): - sensitivity of 94 to 100 percent; - specificity of 90 to 95 percent - a standard screening device in clinical studies of delirium Evaluation (3) Investigating medical etiologies: – Fluid and electrolyte disturbances (dehydration, hyponatremia and hypernatremia) – Infections (urinary, respiratory, skin and soft tissue) – Drug or alcohol toxicity – Withdrawal from alcohol – Withdrawal from barbiturates, benzodiazepines, and SSRI – Metabolic disorders (hypoglycemia, hypercalcemia, uremia, liver failure, thyrotoxicosis) – Low perfusion states (shock, heart failure) – Postoperative states, especially in the elderly Evaluation (4): medication review Differential Diagnosis 1. 2. Sundowning: a frequently seen but poorly understood; seen in evening hours; typically in demented, institutionalized patients. Focal syndromes Temporal-parietal: patients w Wernicke’s aphasia – not comprehend, obey, seem confused; but restricted to language. – Occipital: Anton’s syndrome of cortical blindness and confabulation – Frontal: bifrontal lesions (eg, from tumor or trauma) often show akinetic mutism, lack of spontaneity, lack of judgment, problems w recent or working memory, blunted or labile emotional responses. 3. Nonconvulsive Status Epilepticus (NCSE): – Requires EEG for detection – Show no classical ictal features – Features: prominent bilateral facial twitching, unexplained nystagmoid eye movements during obtunded periods, spontaneous hippus, prolonged “ post-ictal state”, automatisms (lip smacking, chewing, swallowing movements). 4. Dementia – Alzheimer’s – cognitive change is insidious, progressive, without much fluctuation, over a much longer time (months to years). – Lewy bodies – similar to Alzheimer’s, but fluctuations and visual hallucinations are more common and prominent. 5. Primary psychiatric illnesses: – Depression (poor sleep, difficulty w attention or concentration) – Mania Laboratory testing Serum electrolytes, creatinine, glucose, calcium, CBC, and urinalysis Drug levels, when appropriate. – Delirium can occur even w “therapeutic” levels (digoxin, lithium, or quinidine) Toxic screen of blood and urine Blood gas: Respiratory alkalosis is due to early sepsis, hepatic failure, early salicylate intoxication. Metabolic acidosis reflects uremia, diabetic ketoacidosis, lactic acidosis, late phases of sepsis or salicylate intoxication, methanol, ethylene glycol Neuroimaging Head CT may be used selectively rather than routinely for evaluating delirium. May not be necessary if: – An obvious treatable medical illness or problem – No evidence of trauma – No new focal neurologic signs are present – Patient is arousable and able to follow simple commands. Head CT may be required if: – Delirium does not improve despite appropriate treatment of underlying medical condition – The neurologic examination is confounded by diminished patient responsiveness or cooperation. Lumbar puncture CSF analysis is the only diagnostic tool for the following mostly treatable conditions in delirium patients: – Bacterial meningitis – Encephalitis – Nonbacterial CSF pleocytosis (eg, aseptic meningitis, carcinomatous meningitis, encephalitis, seizures) – Elevated CSF glutamine concentration in hepatic encephalopathy – Elevated opening pressure due to increased ICP LP is mandatory when the cause of delirium is not obvious. EEG Should be obtained for any patient with altered consciousness of unknown etiology. Useful to: – Exclude seizures, esp. nonconvulsive or subclinical seizures – Confirm the diagnosis of certain metabolic encephalopathies or infectious encephalopatides Nonconvulsive seizures lack motor manifestations or convulsions, but may impair consciousness. Nonconvulsive status epilepticus may cause continuous or fluctuating impairment of consciousness. Metabolic encephalopathies may show diffuse bilateral slowing of background rhythm and high wave amplitude. Viral encephalitis may show diffuse background slowing and occasional epileptiform activity. Treatment 1. Multicomponent intervention Standardized protocols to control six risk factors for delirium: cognitive impairment; sleep deprivation; immobility; visual impairment; hearing impairment; and dehydration. Of 852 hospitalized pts aged 70 or older; resulted in significant reduction in the number of delirium episodes vs usual care ( 62 vs. 90) and in the total number of days w delirium (105 vs 161) Inouye, Bogardus, Charpentier. A Multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium. NEJM 1999. Managing disruptive behaviors Physical restraints should be used only as a last resort since they frequently increase agitation and create additional morbidity. Hospital environment, characterized by high ambient noise, poor lighting, lack of windows, frequent room changes, and restraint use, often contribute to worsening confusion. Frequent reassurance, touch, and verbal orientation from familiar persons lessen disruptive behaviors. Psychotropic medication A review by the Cochrane Collaborative found only one high-quality randomized trial, which compared haloperidol, chlorpromazine, and lorazepam in the treatment of delirium Recommendation: low-dose haloperidol (0.5 to 1.0 mg PO, IV, or IM) be used to control agitation or psychotic symptoms. Jackson, Lipman. Drug therapy for delirium in terminally ill patients. The Cochrane Library, issue 2, 2004. Older patients are more likely to experience severe extrapyramidal effects w haloperidol (akathisia, potential fatal neuroleptic malignant syndrome) The newer antipsychotic agents (risperidone, olanzapine) have fewer extrapyramidal side effects. Benzodiazepine (lorazepam 0.5 to 1.0 mg) have a more rapid onset of action (5 min after parenteral), but they commonly worsen confusion and sedation. Drug of choice only in cases of sedative drug and alcohol withdrawal. Summary : Delirium workup scheme Summary : Common causes of Delirium Summary: common culprit drugs