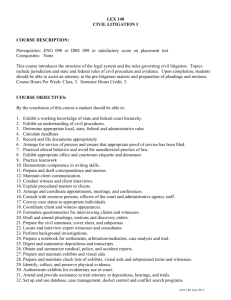

- UVic LSS

advertisement