Kotcher Kendall Kotcher Prof. Gerber WRA 150/36 4 April 2013 Your

advertisement

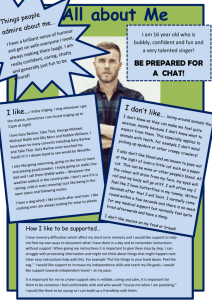

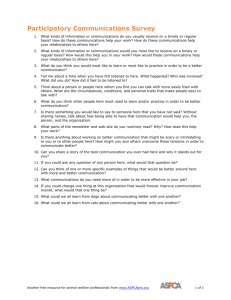

Kotcher 1 Kendall Kotcher Prof. Gerber WRA 150/36 4 April 2013 Your New Prescription: Music As a first year college student, I’d be lying if I said I haven’t been stressing out over a variety of reasons. On Mondays, the hardest day getting back into the week, I start my day with Calculus. I leave that class fuming almost every single day because of the teaching assistant I have. Then I trudge along to Intro to Technical Theatre, which isn’t so bad. Then I make a 2-mile hike through snow, hail, rain, ponds, rivers, whatever Michigan State University’s campus has to throw at me, to get to my choir class. Usually all of my Mondays are hard on me. There was one particular Monday where I woke up with a sore throat, burned the inside of my nose with salt water, fell asleep in calculus, was splashed by someone’s umbrella, was served cold pasta, was served cold pizza, forgot my theatre notes, listened to a boring theatre department professor candidate, and then had to make that 2 mile walk in the pouring rain to choir. One would conclude that that Monday sucked. However, that Monday was not over. Going to choir class that day completely turned my day around. My 3 energetic, passionate, and hilarious directors had us create beautiful and incredible music that brightened up my mood. Having that one music class changed my mood, and my outlook on those drag of a Mondays. If music has the ability to change people’s moods so drastically, then shouldn’t it be used to help people? Music’s powerful affect on people has opened up the growing clinical field of Music Therapy. Therapy “is the clinical and evidence-based use of music Kotcher 2 interventions to accomplish individualized goals within a therapeutic relationship by a credentialed professional who has completed an approved music therapy program” (Musictherapy.org FAQ 1). It’s an established and developing profession that uses music in a therapeutic environment with specialists and patients to address physical, emotional, cognitive, and social needs. A qualified patient’s strengths Figure 2. A music therapist works with a patient in her hospital room. During the therapy session they sing, listen to song lyrics, and play music to help her relax and express herself. them by creating, therapist assesses a and needs, and then treats singing, moving to, and/or listening to music (See Figure 2). Using music as a healing tool dates back to World War I and World War II. Amateur and professional musicians went to Veteran hospitals around the United States to play for thousands of veterans suffering from physical and emotional trauma from the wars. The musicians made veterans happy and distracted the war heroes from their trauma. “The patients' notable physical and emotional responses to music led the doctors and nurses to request the hiring of musicians by the hospitals” (American Music Therapy Association 1). It was soon clear that the musicians needed training. Therefore, the first college degree program for Music Therapy was created at Michigan State University in 1944 and has expanded to prestigious universities all over the country. Kotcher 3 Music Therapy is extremely effective because it directly manipulates the brain’s operations. Everyone’s brain works differently and has a unique electric make up. Music Therapists can use an electroencephalogram (EEG shown in Figure 1) to monitor the brain’s “musical score.” The EEG measures frequencies in the brain and creates two musical tracks—one to listen to for relaxation and one for stimulation. The music is specifically contoured to the brain of the patient. One psychiatrist played his specific CD during a presentation and “40% of the audience started getting headaches.” This music for the brain “has been shown to significantly Figure 1. An EEG visually depicts the brain waves at different states. increase melatonin levels, [which is] a critical hormone in achieving restful sleep” (Peake, Par 15). Even music that’s not contoured to you can still have lasting effects. Not only can the therapy relax you, it can energize you too. According to a survey of high school and college music students, seven out of eight people reported that listening to music helped them perform better when working out (Kotcher). Music Therapy can be used to directly work with the brain to manipulate someone to be relaxed or energized. Music Therapy can also stimulate other parts of the body like the immune system. There is a genre of music that the therapy uses called designer music. This music consists of a variety of rhythms and melodies that produce a particular desired result. In a study performed by Dr. Alan of Southampton General Hospital, participants were asked to think of a person or an activity that gave them the feeling of appreciation. Participants Kotcher 4 then listened to three different genres of music on separate days: New Age, Rock, and Designer. After thinking the appreciative thought, participants showed a forty percent increase in immunoglobulin A (an anti-body found in fluid bodily secretions, AKA IgA). Dr. Alan then tested their saliva after they listened to each genre of music and discovered that the Designer music yielded the highest concentration of IgA with an increase of 140%. The direct correlation between the music therapy and the immune-fighting antibodies proves that music can be used as an easy alternative to promoting good health (Pouliot 1). While Music Therapy can be used as preventative care and can alter current moods, it can also be used to treat the human body after illnesses. There are medical conditions that are severe enough to not be treated effectively by medicine. However, Music Therapy has ousted this obstacle by treating patients with strokes. In a study performed by Dr. Teppo Sarkamo, a neurologist at Helsinki University, patients who listened to music showed a significant increase in brain function than those who listened to audio books or who did neither. Three months after the patients suffered from a stroke, Dr. Sarkamo calculated that “the patients who listened to audio books recovered eighteen percent of their verbal memory. Those that listened to music regained sixty percent, and those that did neither regained twenty-nine percent” (Christian 113). These patients were able to regain parts of their brain that were wiped out from their stroke—a challenge that could not be overcome by medicine. Music Therapy is equally as effective as clinical therapy and medicine. Normally, people go to therapists in hopes of becoming emotionally stable—like after a death of a close family member. Adrianna Fay, a college student majoring in Music Therapy at Kotcher 5 Purdue University, tells a story about how a girl recovered from a death of a family member, through music: “My professor had a client whose grandfather had died six years ago. The girl was quite close to her grandfather and didn't take his death well. So much so that every time his name was brought into a conversation or a picture sat in someone's living room the girl would hysterically cry and scream. My professor performed lyric analysis in which she found a Vince Gil song that the girl loved and had her write a tribute (through lyrics) to her grandfather. She performed it for her family and was able to talk about or see pictures of her grandfather. It has now become a family tradition for her to perform it” (Fay 2013). This is an inspirational example of how music therapy—an extremely easy and effective treatment—can help someone who cannot be helped through medicine. Laurel Fontaine, a stroke victim, also got to experience the positives of music therapy. Eleven-year-old Laurel got a stroke and lost eighty percent of her left-brain. The significant brain damage took away her ability to speak. “After a year of conventional speech therapy, Laurel could speak only a word or two at a time” (Knox, Par 20). Desperate for recovery, Laruel’s Mother enrolled her in a music therapy research project referred to as “singing therapy.” This type of music therapy was so lucrative because “the right side of Meyerson's brain – the singing part that's being retrained to ‘speak’ – is good at melody and pitch, but it's not as fast as the left-sided language center, called Broca's area” (Knox, Par 12). Within four months, Laurel saw permanent effects with singing therapy. "I'm singing in my head and talking out loud without singing. I do it, like, really quick" Kotcher 6 (Knox, Par 22). The girl who recovered from her grandfather’s death and Laurel both had life changing experiences just by choosing music therapy over traditional treatments. Not only has music therapy proven more effective than traditional medical treatments, it has no side effects. The huge problem with drugs and prescription medication is the harmful side effects they have. In almost every television commercial about a drug they list the side effects that can be anywhere from trouble sleeping to heart attacks, diarrhea, amnesia, loss of vision, loss of hearing, constipation, discoloration of the skin, loss of hair and death (Freeman 2-11). It’s terrifying to pick up a prescription and find out that you’re one of the “rare cases” that has a heart attack. However, music therapy doesn’t have these terrifying effects. The only possible effect it could have is resurfacing “negative feelings from the past; these can be addressed by working with the music therapist” (Arnold, Par 7). Music therapy has drastic positive impacts with little cost. Music therapy is a critical field to invest in for it’s effective, easy, and safe. “I believe that if I didn't have music, I wouldn't be the same person I am today... Without it I wouldn't be able to properly express myself when I'm feeling down/angry/overjoyed... Having a music class makes my whole day better… Music has probably saved my life” (Kotcher). These are true feelings from high school students about how music has affected them. Music is powerful and can be used for more than just leisure. It can be used as a therapy to cure the sick, ease the pain, and keep people alive. Throw away the prescriptions and look into music therapy to experience the powerful positive results. Kotcher 7 Works Cited "American Music Therapy Association." American Music Therapy Association. American Music Therapy Association, n.d. Web. 14 Mar. 2013. <http://www.musictherapy.org/>. Arnold, Robert. "# 108 Music Therapy." # 108 Music Therapy. Medical College of Wisconsin, n.d. Web. 28 Mar. 2013. <http://www.eperc.mcw.edu/EPERC/FastFactsIndex/ff_108.htm>. Christian, Margena A. "Study finds listening to music could improve recovery from stroke .(LIFESTYLES) (Brief article) (Clinical report)." Jet 113.9 (March 10, 2008): 50(1). General Reference Center Gold. Gale. Library of Michigan. 22 Feb. 2009 <http://0-find.galegroup.com.elibrary.mel.org/itx/start.do?prodId=GRGM>. "Electroencephalogram." The Free Dictionary. Saunders, 2007. Web. 1 Apr. 2013. <http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/electroencephalogram>. Fay, Adrianna. Interview by Kendall Kotcher. "Music Therapy Research." Web. 19 Mar. 2013. Freeman, Shanna. "Top 10 Weirdest Prescription Drug Side Effects." Discovery Health. Discovery Communications, n.d. Web. 28 Mar. 2013. <http://health.howstuffworks.com/medicine/medication/10-weird-prescriptiondrug-side-effect.htm>. Knox, Richard. "Singing Therapy Helps Stroke Patients Speak Again." NPR. NPR, 26 Kotcher 8 Dec. 2011. Web. 28 Mar. 2013. <http://www.npr.org/blogs/health/2011/12/26/144152193/singing-therapy-helpsstroke-patients-speak-again>. Kotcher, Kendall. College and High School Music Students. "Music Therapy." Survey. 19 Mar. 2013. "Music Therapy at Children's Hospital Colorado." Children's Hospital Colorado. University of Colorado School of Medicine, 2013. Web. 01 Apr. 2013. <http://www.childrenscolorado.org/conditions/psych/creative-arts-therapy/musictherapy.aspx>. Peake, Michael. "Brain Music: Turn On, Tune In, Feel Better." Medill Reports. Northwestern University, 03 Mar. 2010. Web. 20 Mar. 2013. <http://news.medill.northwestern.edu/chicago/news.aspx?id=159319>. Pouliot, Janine S. "The power of music." World and I 13.n5 (May 1998): 146(8). Academic OneFile. Gale. Library of Michigan. 21 Feb. 2009 <http://0-find.galegroup.com.elibrary.mel.org/itx/start.do?prodId=AONE>.