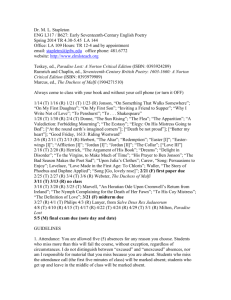

Ben Jonson

advertisement

Ben Jonson And the Cavalier poets Contents: - Benjamin Jonson’s biography - Benjamin Jonson’s literary creation: - Volpone - Every Man in his Humour - The Alchemist - Benjamin Jonson and his followers ( The Cavalier poets) Benjamin Jonson (circa 11/06/1572- 06/08/1637) He was born in Westminster, London in 1572, the posthumous son of a clergyman. His father died a month before Ben’s birth, and his mother remarried two years later, to a master bricklayer. Jonson attended school in St. Martin’s Lane, and was later sent to Westminster School. About 1589, probably because of his poverty, instead of pursuing a university education he left Westminster to follow his stepfather’s trade of bricklaying. Ben Jonson married some time before 1592. The registers of St. Martin’s Church state that his eldest daughter Mary died in November, 1593, when she was only six months old. His eldest son Benjamin died of the plague ten years later, and a second Benjamin died in 1635. ‘Shakespeare was the Homer, or father of the dramatic poets; Jonson as the Virgil, the pattern of elaborate writing.’ Essay on Dramatic Poesy -1668- John Dryden By September of 1597, Jonson had a fixed engagement in the Lord Admiral’s acting company, then performing under Philip Henslowe’s management at The Rose. In 1597 he was imprisoned for his collaboration with Thomas Nashe in writing the play Isle of Dogs. In 1598 , Jonson produced his first great success, Every Man in his humour. On September 22, 1598, Jonson killed his fellowactor, Gabriel Spencer, in a duel. When brought to trial, he confessed and claimed right of clergy; his property was confiscated and his thumb branded. On January 6, 1605, he began his great career of masque- writing with the production of The Masque of Blackness at Whitehall, and during the reign of James he finished twenty of the thirtyseven masques presented at court. Early in 1606 he composed Volpone. ‘Shakespeare was the Homer, or father of the dramatic poets; Jonson as the Virgil, the pattern of elaborate writing.’ Essay on Dramatic Poesy -1668- John Dryden On July 19, 1619, Jonson was made M. A. of Oxford. In 1628 he became city chronologer of London. He had suffered debilitating stroke that year, and in the following year he was granted a pension of £ 100 by King Charles. He died on August 6, 1637, and was buried three days later in Westminster Abbey. Several stories surround his unusual burial in the Abbey. The first says that, dying in great poverty, Jonson begged for '18 inches of square ground in Westminster Abbey' from Charles I. Another says that 'one day being railed by the Dean of Westminster about being buried in Poets' Corner, Jonson is said to have replied:" I am too poor for that, and no one will lay out funeral charges upon me. No sir, 2 feet by 2 feet will do for all I want." Either way, Jonson was buried in the Nave of the Abbey standing on his feet. Theory of Humours Ben Jonson modelled himself on classical authors and his characters were types like those of Theophrastus, or were intended to illustrate the theory of Humours. In early Western physiological theory, a Humour is one of the four fluids of the body that were thought to determine a person's temperament and features. In the ancient physiological theory still current in the European Middle Ages and later, the four cardinal humours were blood, phlegm, choler (yellow bile), and melancholy (black bile); the variant mixtures of these humours in different persons determined their “complexions,” or “temperaments,” their physical and mental qualities, and their dispositions. The ideal person had the ideally proportioned mixture of the four; a predominance of one produced a person who was sanguine (Latin sanguis, “blood”), phlegmatic, choleric, or melancholic. Table of the four humours in Renaissance and Elizabethan time Humour Body substance Produced by Element Qualities Complexion and body type Personality Sanguine blood liver air Hot and moist Red-cheeked, corpulent Amourous, happy, generous, optimistic, irresponsible Choleric Yellow bile spleen fire Hot and dry Red-haired, thin Violent, vengeful, shorttempered, ambitious Phlegmatic phlegm lungs water Cold and moist corpulent Sluggish, pallid, cowardly Melancholic Black bile Gall bladder earth Cold and dry Sallow, thin Introspective, sentimental, gluttonous Volpone - Things to remember about Volpone and Ben Jonson’s style - Plot - Monsters in Volpone Things to remember: Ben Jonson - had a passion for the varied and colourful London life of his time - had a boisterous and even cruel sense of humor - showed impressive originality even when working within classical models Volpone is characterised with: - savagery and humour - moral feeling and grim characterisation of the monstrous absurdities of human nature It could be read as: - a moral exemplum - a beast fable (a beast fable is a short tale in which the principle actors are animals. Jonson’s characters are people, but they havethe characteristics of animals, as their names reveal) - a satire ( on English life in General) - a humour play - a tragedy The play Volpone is very pessimistic. A principle theme is the way that greed can make people gullible. In playing their trick, which focuses on exposing the greed of others, Volpone and Mosca also expose their own selfishness and greed (which is greater than that of the victims) The setting is Renaissance Italy, accepted by the English imagination of the time as the proper home of vice. The characters are deliberately restricted in scope in the interests of the satiric purpose. They are pretty shallow and rearely show genuine emotions. They could be described as two-dimentional. There is no real catharsis in the play, no true triumph of good over evil. Bonario and Celia are not saved by their gods but because the evil people tell on each other. Plot Inspired by classical stories of the of the captatores, the legacy hunters of Rome, described by Petronius and others, Jonson created with Volpone the story of a cunning rich man who feigns a mortal illness so that his wealthy neighbours would court his favour in hopes of becoming his heir. But Volpone ( Big Fox) cannot act alone. His servant Mosca (Fly) plays on the legacy hunters’ hopes and fears acting as Volpone’s agent but also capable of double-cross. He promises each of the legacy hunters that Volpone will name him as his heir, and he urge each of the ‘birds of pray’ to speed the process by showing Volpone examples of their good will and respect through what else but gifts. Thus each is induced to bring gifts to the supposedly dying Volpone, with the idea that they will not only receive gifts back when he dies but all his other treasures as well. The eager legacy hunters willingly hasten to prove the devotion to Volpone, but their eagerness has a malevolent side: they become willing to betray and destroy closest to them in hopes of getting the big reward. However, unlike in the conventional comedy, good does not necessarily triumph at the end, for even the state itself is shown to be easily corrupted. Volpone’s avarice seems to be epidemic, and good characters like Celia and Bonario stand at the mercy of evil. Monsters in Volpone Nano the Fool- Nano’s body, rather than his mind or spirit, is defective. His deformity is nevertheless as much behavioural as physical, because Nano performs as a ‘dwarf’ for Volpone. Nano is partly in controlof his own identity because he manipulates his deformity to amuse Volpone. He is quite successful at seizing control of his situation. Castrone (Castrated) - His defect is one of the body- physical. Castrone succeeds in negotiating Venetian society despite his infirmity. In fact, since no one actually has sex in this play, Castrone can be said to symbolise perfectly the condition of the society. Androgino- as a hermaphrodite, has a physical defect as well. Yet we might say that he is more ‘perfect’ or complete than any other character in the play, since he has two sets of genitals. Sex is not important to Androgino, either in terms of intercourse or in terms of gender. Corvino (the Raven) - his deformity, unlike those of the previous character, is ethical, spiritual, or moral rather than physical. He has a strong need for others’ approval, he is egocentric, and he exploits his own virtuous and beautiful wife (Celia). He goes down the social scale from merchant to pimp. Using his wife to gain more money, he is less sufficient than the previous ‘monsters’. He is at once old and phlegmatic and choleric. As a ‘Raven’ he is a scavenger. He is unable to make normal human connections. Sir Politic- Would- Be - He is mentally and spiritually empty. He needs the company of others, but does not make any human and intellectual connections.He too is egocentric, pretentious, and shows the dangers of being too ‘sanguine’ in a humours psychology. Like his wife, Sir Politic creates himself through language, through talk, although he does not know what he is talking about. At the end of the play he is disillusioned, which is a fate the physical monsters do not endure. He is also deceptive and plotting, and none of the ‘real monsters’ have to pretend to be what they are not. Lady Would-Be - like her husband, she is self-absorbed and shallow. She is also mean to her servants. Lady Would-Be tries to imitate the Italian courtesans, which suggests that she aspires to sexual voraciousness that no one else in the play can attain. She is the most talkative character in the play, which means she must create herself through speech, while the physical monsters are identifiable by there physical appearance. Lady Would- Be is very bright and colourful like a ‘parrot’, she wants to be an object of amazed sight, like Nano, Castrone and Androgino. Corbaccio (the Carrion Crow) - He is physically weak and weak in character. He is basically phlegmatic, but disinherits his own son (Bonario), which suggests that Corbaccio does not understand human connections. He is a scavenger, attracted to bright things. He does not hear well, which makes him seem less human. Every Man in His Humour Every Man in His Humor, not Jonson's greatest but probably his most influential play, first acted by the Lord Chamberlain's Men in 1598, was entered in the Stationers' Register August 4, 1600, and was printed the following year. This version, with its scene laid in Florence and its chief characters bearing Italian names, was later carefully revised by Jonson for publication in the 1616 folio. The scene was shifted to London, the characters were given English names and were more individualized, and the expression in general was much altered, the most notable change being the excision of Lorenzo's (Knowell's) defense of poetry at the end of the play, a passage which delayed the action and to Jonson's mind probably violated the principle of decorum because it was unsuited to such a gathering. The plot is of Jonson's own invention, but from Chapman's An Humorous Day's Mirth (1599) he drew hints for the gull, and from Plautine comedy he derived the suggestion of a pair of elderly persons deceived and outwitted by a pair of clever, young men, is well as the shrewd serving-man and the braggart soldier. In its preservation of unity of tone, its observance of the unities of time, place, and action, and its truth to what is typical or normal in action and character, the play shows a definite adherence to the requirements of classical comedy as formulated by Renaissance criticism, notably by Sidney in his Defense of Poesy, published in 1595. The prologue to the later version of the play presents Jonson's essential dramatic theory for all his comedies. He here expresses condemnation of the wildly romantic tendencies in the drama and declares his purpose to "show the image of the times" by employing "deeds and language such as men do use," and to make follies, not crimes, his chief consideration. The Alchemist Jonson's most popular and, in the light of his theory, most perfect play, The Alchemist, was written during the plague season of 1610 for performance before Londoners who, like Lovewit, would return to their homes after all danger of infection had passed. The practice of alchemy was as common to the life of the time as it had been in the Middle Ages, and exposures of impostures such as Jonson portrays were so frequent in life as well as in literature that it has been impossible to discover any source for this aspect of the play. From Plautus' Mostellaria he may have derived the quarrel scene at the opening of the play and the idea of the unexpected return of the owner of a house in which rogues are carrying on their practices; and he may have taken certain minor suggestions from Plautus' Pœnulus and Erasmus' colloquy on the alchemist. The construction of the play reveals the hand of the master. All the unities are rigidly observed. The action takes place in a single day at a house in the Blackfriars district of London, and, while the three intrigues remain distinct, each being a unit in itself, they are actuated by similar motives, are pervaded by one comic tone, and are related to the general plan. Suspense as to the outcome of the action constantly increases to the very Cavalier poets Though the Cavalier Poets only occasionally imitated the strenuous intellectual conceits of Donne, and his followers, and were fervent admirers of Jonson's elegance, they took care to learn from both parties. In fact, reading the work of Thomas Carew, Sir John Suckling, Richard Lovelace, Lord Herbert, Aurelian Townshend, William Cartwright, Thomas Randolph, William Habington, Sir Richard Fanshawe, Edmund Waller, and the Marquis of Montrose, it is easy to see that they each owe something to both styles. In fact the common factor that binds the cavaliers together is their use of direct and colloquial language expressive of a highly individual personality, and their enjoyment of the casual, the amateur, the affectionate poem written by the way. They are 'cavalier' in the sense, not only of being Royalists (though Waller changed sides twice), but in the sense that they distrust the over-earnest, the too intense. They accept the ideal of the Renaissance Gentleman who is at once lover, soldier, wit, man of affairs, musician, and poet, but abandon the notion of his being also a pattern of Christian chivalry. They avoid the subject of religion, apart from making one or two graceful speeches. They attempt no plumbing of the depths of the soul. They treat life cavalierly, indeed, and sometimes they treat poetic convention cavalierly too. For them life is far too enjoyable for much of it to be spent sweating over verses in a study. The poems must be written in the intervals of living, and are celebratory of things that are much livelier than mere philosophy or art.