Social Participation - American Counseling Association

advertisement

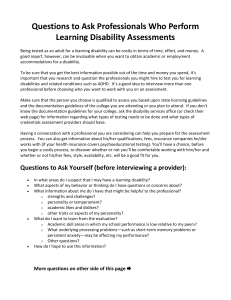

Effects of Burden of Environmental Inaccessibility and Perceived Stigma on Social Participation and Acceptance of Disability among Adults with Physical Disability Gloria Y. K. MA Diversity and Well-being Lab Department of Psychology 1 The Chinese University of Hong Kong Aim of study • To examine the mechanism of how environmental factors would affect social participation and psychological adjustment in people with physical disability (PWPD) in Hong Kong. Environmental Barriers • Burden of environmental inaccessibility • Perceived stigma Social Participation • Community exposure (objective) • Social enfranchisement (subjective) Psychological Adjustment • Acceptance of disability an important indicator of adjustment to disability Social Participation “Involvement in Life Situations” in ICF by WHO 9 Domains of Participation • • • • • • • 1) learning and applying knowledge, 2) general tasks and demands, 3) communication, 4) mobility, 5) self-care, 6) domestic life, 7) interpersonal interactions and relationships, • 8) major life areas, e.g. education and employment, • 9) community, social and civic life. Qualifiers • Performance • Capacity ** the focus is frequency of “doing” and level of functioning (Cummins & Lau, 2003). 3 Social Participation • “Doing in life situation” is merely “community exposure” but not “full participation” (Cummins & Lau, 2003) • It is the subjective feeling of sense of belonging to the community that really contributes to one’s participation and psychological wellbeing. • Qualitative findings suggested that the core of social participation was the subjective appraisal of their social participation, the sense of being valued, and having autonomy and control in societal activities (Brown, 2010; Dijkers, 1998; Lysack et al., 2007). 4 1. Visibility of the non-typical body movements, deformities, and/or use of assistive devices may elicit stereotypical signs of weakness and dependence; 2. Unfriendly gaze by the public on the street (Brown, 2010); 3. Public kindness, which is perceived by PWPD as an patronizing and embarrassing act (Cahill & Eggleston, 1988). • Perceived stigma as a major attitudinal barrier Being devalued, unwelcomed by the society, and discriminated against in employment and recreational activities (Brown, 2010; Gray, Gould, & Bickenbach, 2003; Rimmer et al., 2004). • Negatively associated with acceptance of disability (Li and Moore, 1998) 5 • Physical environment sets the stage for social participation to occur, affecting the success and enjoyment of processes like wayfinding and navigation. Environmental inaccessibility as physical barrier • Environmental accessibility = Broadly defined as whether the natural or built environment and transportation system is physically accessible. • Influence both the objective community exposure and the subjective appraisal of social participation among PWD. (Meyers, Anderson, Miller, Shipp, & Hoenig, 2002; Nilay Evcil, 2009; Putnam et al., 2003; Rimmer et al., 2004; Schoell, 2009; Stark, Hollingsworth, Morgan, & Gray, 2007; Steinfeld and Danford, 1999) 6 • Difficult to do actual audit or recall the number of barriers as required by many instruments; although they have their own advantages • How they perceive the physical accessibility and thus anticipated burden may play important role Burden of inaccessibility associated with stigma • Burden of environmental inaccessibility may not be localized in particular geographical location, nor whether he/she has carried out that activity before. • Architectural buildings would create social experiences that express or reinforce certain social values and perceptions towards particular groups of people (Cahill & Eggleston, 1988; Conell & Sanford, 1999; Iwarsson & Stahl, 2003; Joines, 2009; Robinson & Thompson, 1999; Steinfeld & Danford 1999). 7 The Present Study Sample • 143 Chinese adults with physical disability from 10 NGOs serving people with disabilities in Hong Kong in 2014. • 56.0% male; mean age = 37.4 years, SD = 15.2, range = 17-78 years • 48.1% congenital; 51.9% acquired disability • 71.5% participants were single • 26.2% attained secondary 4-5 education 9 Instruments Self-report questionnaire with scales having reliability of .7 or above in Cronbach’s alpha. Constructs Measures 1. Burden of Environmental -- Access Subscale of Physical Disability Stress Inaccessibility Scale (Furlong & Connor, 2007) -- 7 items from the Disabled Related Stress Scale (Rhode et al., 2012) -- 4 self-constructed items on transport 2. Perceived Stigma 7 items on perceptions of stigma (Brown, 2010) 3. Community Exposure 18 items adapted from the Participation Objective, Participation Subjective (Brown et al., 2004) 4. Social Enfranchisement Participation Enfranchisement Scale (Heinemann et al., 2011) 5. Acceptance of Disability Acceptance of Disability Scale – Revised (Grommes & Linkowski, 2004; Linkowski, 1971) 10 Statistical Analysis • Structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted to examine the overall fit of the proposed model to the observed variance/covariance matrices of the data using the maximum likelihood method in EQS 6.1 for Windows. • Goodness-of-fit was indicated by indices including CFI and NNFI greater than .95, SRMR of .08 or below, and RMSEA of .06 or below (Hu & Bentler, 1999) 11 Results 12 Results • SEM showed satisfactory model fit of the proposed structural model to the data: χ2 = 49.24, (df= 38, p = .10), χ2/df = 1.30, GFI = .92, CFI = .98, NNFI = .98, SRMR = .04, RMSEA = .06. -.29* .51* -.46* -.27* .59* non-significant direct path Figure 2. Standardized path loadings. *p < .05. 13 Results • The model explained 65% of variance in acceptance of disability. • Significant direct association between environmental inaccessibility and perceived stigma. • Significant indirect effect of environmental inaccessibility on acceptance of disability via perceived stigma and social participation (B = -.21, β = -.49, p < .05). • Independent samples t-test showed that participants having congenital physical disability -- had significantly better social enfranchisement than having acquired physical disability; t (93) = 2.60, p < .05; and -- had significantly higher acceptance of disability than participants with acquired physical disability, t (92) = 2.56, p < .05. Discussion 15 Promoting universal design The significant and direct association between the burden of environmental inaccessibility and perceived stigma. • New perspective of stigma reduction through promoting universal design 16 Perspective of counselling service The significant and indirect effects of burden of environmental inaccessibility on acceptance of disability through perceived stigma and social participation • Social experiences would influence the perceptions of self and one’s own disability (Li & Moore, 1998). • Consistent with the notion of social model of disability. • Counselling services should adopt macro perspectives to enhance disability adjustment. 17 Personalized counselling services • Acquired physical disability (e.g. stroke) is generally a sudden and drastic challenge to one’s life, imposing intense stress and burden to the person. They may face great changes in daily life; and it may take considerable duration of time to gradually adapt to the social life. • Counsellors should take into account of both their clients’ nature of disability and their social experiences when designing personalized counselling services. 18 • Cross-sectional sample and small sample size; • Findings may not be generalized to people with all types of physical disability (and other disabilities); Limitations • No comparison on the effects of actual physical barriers and the burden of environmental barriers. 19 • association of environmental accessibility and stigmatization • community exposure VS social enfranchisement Future research directions • different dimensions of acceptance of disability • effectiveness of different counselling therapeutic interventions 20 Acknowledgments • The present study was funded by the I.CARE Programme Research and Studies 2013-14, the Chinese University of Hong Kong (reference no.: R01-13). • We would like to express our heartfelt thanks to the participating organizations and all participants. • Research helpers and members of the Diversity & Wellbeing Laboratory in data collection, data analysis, and peer support. 21 e-mail: gykma@psy.cuhk.edu.hk Let’s build a truly barrier-free society together! 22 References Brown, M., Dijkers, M. P., Gordon, W. A., Ashman, T., Charatz, H., & Cheng, Z. (2004). Participation objective, participation subjective: a measure of participation combining outsider and insider perspectives. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 19(6), 459-481. Brown, R. L. (2010). Physical disability and quality of life: The stress process and experience of stigma in a chronically-strained population. Unpublished thesis. Cahill, S. E., & Eggleston, R. (1988). Reconsidering the stigma of physical disability: Wheelchair use and public kindness. The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 18(4), 591-613. Conell, B. R., & Sanford, J. A. Research implications of universal design. In: E Steinfeld, GS Danford (eds). Enabling Environments. Measuring the Impact of Environment on Disability and Rehabilitation. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 1999. Cummins, R. A., & Lau, A., (2003). Community integration or community exposure? A review and discussion in relation to people with an intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 16, 145-157. 23 References Dijkers, M. (1998). Community integration: Conceptual issues and measurement approaches in rehabilitation research. Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation, 4(1), 1-15. Furlong, M., & Connor, J. (2007). The measurement of disabilityrelated stress in wheelchair users. Archives in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 88(10), 1260-1267. Gray, D. B., Gould, M., & Bickenbach, J. E. (2003). Environmental Barriers and Disability. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, 20(1), 29-37. Gray, D. B., Gould, M., & Bickenbach, J. E. (2003). Environmental Barriers and Disability. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, 20(1), 29-37. Groomes, D. A. G., & Linkowski, D. C. (2007). Examining the structure of the Revised Acceptance Disability Scale. Journal of Rehabilitation, 73(3), 3-9. Heinemann, A. W., Lai, J-S., Magasi, S., Hammel, J., Corrigan, J. D., Bogner, J. A., & Whiteneck, G. G. (2011). Measuring participation enfranchisement. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 92(4), 564-571. Hu, L. T., Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1-55. 24 References Iwarsson, S., & Stahl, A. (2003). Accessibility, usability and universal design---positioning and definition of concepts describing personenvironment relationships. Disability and Rehabilitation, 25(2), 57-66. Joines, S. (2009). Enhancing quality of life through universal design. NeuroRehabilitation, 25, 313-326. Li, L., & Moore, D. (1998). Acceptance of disability and its correlates. The Journal of Social Psychology, 138(1), 13-25. Linkowski, D.C. (1971). A scale to measure acceptance to disability. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 14(4), 236-244. Lysack, C., Komanecky, M., Kabel, A., Cross, K., & Neufeld, S. (2007) Environmental factors and their role in community integration after spinal cord injury. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74, 243254. Meyers, A. R., Anderson, J. J., Miller, D. R., Shipp, K., & Hoenig, H. (2002). Barriers, facilitators, and access for wheelchair users: Substantive and methodologic lessons from a pilot study of environmental effects. Social Science & Medicine, 55, 1435-1446. Nilay Evcil, A. (2009). Wheelchair accessibility to public buildings in Istanbul. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 4(2), 76-85. Putnam, M., Geenen, S., & Powers, L. (2003). Health and wellness: People with disabilities discuss barriers and facilitators to well being. Journal of Rehabilitation, 69, 37-45. 25 References Rhode, P. C., Froehlich-Grobe, K., Hockemeyer, J. R., Carlson, J. A., & Lee, J. (2012). Accessing stress in disability: Developing and piloting the Disability Related Stress Scale. Disability and Health Journal, 5, 168-176. Rimmer, J. H., Riley, B., Wang, E., Rauworth, A., & Jurkowski, J. (2004). Physical activity participation among persons with disabilities. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 26(5), 419-425. Robinson, J. W., & Thompson, T. (1999). Stigma and architecture. In Steinfeld, E., & Danford, G. S. (Eds.), Enabling environments: Measuring the impact of environment on disability and rehabilitation (pp. 251270). Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. Schneidert, M., Hurst, R., Miller, J., & Ustun, B. (2003). The role of environment in the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Disbility and Rehabilitation, 25(11-12), 588595. Schoell, D. M. (2009). Moving vertically: A research method, grounded in the social sciences, about the built environment's influence on social integration. Unpublished Thesis. State University of New York at Buffalo. Stark, S., Hollingsworth, H. H., Morgan, K. A., & Gray, D. B. (2007). Development of a measure of receptivity of the physical environment. Disability and Rehabilitation, 29(2), 123-137. Steinfeld, E., & Danford, G. S. Theory as a basis for research on enabling environments. In: Steinfeld, E., & Danford, G. S. (eds) Enabling Environments. Measuring the Impact of Environment on Disability and Rehabilitation. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 1999. 26