Economic Idea - Wright State University

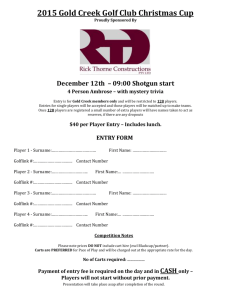

advertisement