Between shouting matches and silence: fostering real dialogue with

advertisement

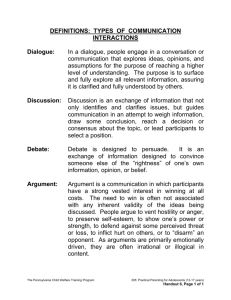

Between shouting matches and silence: fostering real dialogue with the public about animal research. Janet D. Stemwedel San José State University dr.freeride@gmail.com The big questions: 1. How to shift from the current state of play to more productive engagement (especially dialogue)? 2. Who, in particular, to try to include in a dialogue of this sort? (Who to try to reach with such dialogue?) Why dialogue? Dialogue is neither a high school debate nor a political point-scoring battle! Dialogue involves laying out positions, questions and really engaging with them. Opponents vs. dialogue partners with shared responsibilities. Dialogue differs from debate. • Debate assumes a winner and a loser. • Dialogue assumes space to articulate your position and your reasons for your position. • Dialogue also assumes listening, asking questions. • Goal is better understanding of everyone’s positions and reasons. • Disagreement at conclusion doesn’t mean you’re doing it wrong! Why bother with dialogue? • Balancing competing interests is hard (and so requires good deliberation). • Better way to deal with disagreements than hoping they’ll go away (or turning to violence). • Keeps participants in touch with the complexities. • Makes it harder to dehumanize “the other side”. A good place to see committed dialogue about animal research: The IACUC Explicitly includes a range of interests and points of view. In a broader sense, the dialogue includes not just committee members but also PIs, institutions, governmental agencies. Dialogues can be challenging! • Require serious thought (even about your own position and reasons) • Commit you to taking your dialogue partner seriously • Usually need something like ground rules and a facillitator Some frequent impediments to this kind of dialogue: 1. Presumptive mistrust of “the other side” 2. Disagreements about the facts 3. Tendency to tangle a number of issues together 4. Fuzziness about what’s actually being claimed 5. Impact of tactics on how the positions and the people advocating them are viewed Scientists and animal activists see different facts. “Everyone is entitled to their own opinion, but not their own facts.” • Should be clear about where our facts come from. • Should be honest about where there are gaps in our knowledge. (Modeling intellectual honesty discourages goalpost shifting.) Being clear about your positions. • Inadequate regulations or inadequate compliance? • Animal welfare or animal rights? • What values are competing and how they get prioritized. Recognizing the range of positions available, or represented. The regulatory status quo is a compromise position! (Regulations reflect something like public will here.) Tying together issues that are separable. • E.g., Scientific questions that can’t be answered without animal use vs. moral status of animals. • Separating them may help you find (limited) areas of agreement, even common ground moving forward. Tactics matter. Hard to give a position fair consideration if it is routinely advanced using questionable tactics (especially violence and intimidation). Tactics matter. Beyond the tactics I myself use to work toward the goal, what other tactics do I accept when used by others? If your main concern is achieving the goal, are there tactics that you yourself would not choose that won't bother you terribly is the goal is achieved? Tactics matter. If you can accept the end result accomplished with these tactics (even if others were the ones who actually used these tactics), is this relevantly different from supporting them? Work to even make safe dialogue possible: • Exposing the tactics that shut down willingness to participate in dialogue. • Getting people to stop using those tactics (and to actively work against others' use of them rather than passively accepting whatever ground seems to be gained through their use). • Promoting rational engagement (especially where there is real disagreement) With whom should we be in dialogue? • Who do we want to reach? • Who can we reach? • Whose concerns ought we to hear? • Don’t want to waste time with people who won’t argue in good faith. Drawing people in from the sidelines. “There are times when I have not trusted my actual dialogue ‘partner’ … but where at the same time I knew that behind/beside/near that person, there were other people who I did trust slightly more – and so, I wasn’t really addressing my ostensible partner so much as I was addressing a range of people including that person.” People worth drawing in: • The general public • Students in classes that include animal use, knowledge built from animal research • Activists who are not extremists • Members of the scientific community who aren’t on the front lines Whose responsibility to enter into dialogue? • Personal safety is not a trivial concern • But, leaving your position to people who don’t value dialogue (or who rely on problematic tactics) has a cost “Playing a zone” in engaging with the public. (Plenty of dialogue opportunities closer to home can support engagement with larger public) It’s OK to: • Voice concerns (about anticipated goalpost moving, whether dialogue partner will understand your point, etc.) • Acknowledge anger, fear, frustration • Acknowledge where your knowledge is gappy • Identify areas of disagreement that are unlikely to be resolved by further facts or rational argument What counts as a positive outcome? • Understanding each other better is real progress. • Understanding the positions and reasons (even our own) better is progress. • Seeing the humanity of the people with whom we’re disagreeing is progress.