microeconomics5_std - Rose

advertisement

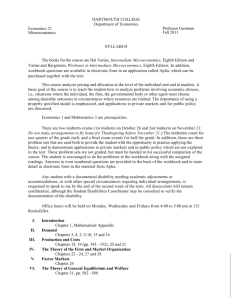

SL354 Intermediate Microeconomics Monday Tuesday Thursday Friday Week 1 Introduction Varian, 1 Budget Constraints Varian, 2 Preferences Varian, 3 Utility Varian, 4 Week 2 Optimal Choice Varian, 5 Consumer Demand Varian, 6 [7] S. & I. Effects Varian, 8 Cooperation, etc. Thaler, 2 – 3 Buying & Selling Varian, 9 Intertemporal Choice Varian, 10 Endowment Effects Thaler, 6 – 8 Surplus, Demand Varian, 14 & 15 Demand, Equilibrium Varian, 15 & 16 Equilibrium Varian, 16 Asset Markets Varian, 11 Uncertainty (Risk) Varian, 12 Uncertainty (Risk) Varian, 12 Diversification Varian, 13 Behavioral Finance Thaler, 9 – 10 Real Financial Markets Thaler, 11 – 12, 14 Pure Exchange Varian, 31 Pure Exchange Varian, 31 Technology Varian, 18 General Equilibrium TBD Welfare Varian, 33 Welfare Varian, 33 Auctions Varian, 17 Auctions Thaler, 5 No Class Asymmetric Information Varian, 37 Asymmetric Information TBD Week 3 Week 4 Week 5 Week 6 Week 7 Week 8 Week 9 Week 10 Exam 1 Consumer Surplus Varian, 14 Exam 2 Risky Assets Varian, 13 Exam 3 Production Varian, 32 Exam 4 Externalities Varian, 34 Exam 5 Externalities Rural Neighbors and the Right to Farm Before you build your dream house in the country, thoroughly investigate the surroundings. During the last several decades, more and more city people have migrated to rural areas to pursue their modern American dreams. They seek a peaceful place in the country, away from the noise and crime of cities. Many choose homes in modest (or not so modest) subdivisions that press into formerly agricultural lands. This intrusion of urban life into rural life results in an inevitable conflict. How surprised some neighbors are to wake up one spring morning to roaring machinery, buzzing flies, the stench of manure and a mist of pesticides in the air. And how angry many become when they learn that they can't do anything about it. The Legal 'Right to Farm' States now give farmers a basic "right to farm" without the fear of lawsuits brought by offended neighbors. As one judge remarked while dismissing a lawsuit against a hog farmer, "pork production generates odors which cannot be prevented, and so long as the human race consumes pork, someone must tolerate the smell.“ Before the right-to-farm laws were enacted (most of them in the 1980s), courts shut down many a farmer's operation because it was a nuisance to the neighbors. For example, a group of annoyed neighbors, whose homes had sprung up around a Massachusetts hog farm, sued and closed it in 1963. Some judges tried to strike a middle ground and ended up applying restrictions that would let the farming operation continue. A Florida court, for example, allowed a hog farm to stay in business but limited how many hogs the farmer could have. The judge also issued instructions on how to store and feed the garbage the hogs were accustomed to eating. Pure Exchange and Externalities B · X’ Good 2 (Externality) · X · A · Good 1 (Income) Pure Exchange and Externalities : The Coase Theorem B · X’ X Good 2 · A · · Good 1 Production Externalities P S’ = S +MSC S [= Marginal Private Cost] D [= Marginal Private Benefit] P’ P* MSC Q’ Q* Optimal Output -- Society’s View [Marginal Social Cost] Q Optimal Output -- Private Market’s View The Coase Theorem Again Coase, “The Problem of Social Cost” (1960) “It is strange that a doctrine as faulty as that developed by Pigou should have been so influential …” “The traditional approach [to the externality problem, the ‘Pigovian’ approach] has tended to obscure the nature of the choice that has to be made. The question is commonly thought of as one in which A inflicts harm on B. But this is wrong. We are dealing with a problem of a reciprocal nature. To avoid the harm to B would be to inflict harm on A … The problem is to avoid the more serious harm.” Ronald Coase 1910 - The Coase Theorem: In the absence of transaction costs, all government allocations of property rights are equally efficient, because interested parties will bargain privately to correct any externality. Implication: Any market plagued by externalities can be made efficient if property rights are clearly defined and assigned, and if transaction (bargaining) costs are negligible. Carbon Tax vs. Cap & Trade Surplus Analysis Carbon Tax P Cap & Trade P S’ = S + tax S P’ S’ S P’ P* P* D Q’ Q* D Q Q’ Q* Q Markets with asymmetric information Varian’s “market for plums and lemons” P S plums : P 44Q ps 2200 Pplums 1925 P̂plums D plums : P 4400 44 Q pd Slemons : P 1100 44Qls 1375 P̂lemons Duncertainquality 1100 Plemons pr plums* D plums prlemons* Dlemons Dlemons : P 3300 44Qld Qˆ plums || 43.75 Q plums Qˆ lemons || || 56.25 Qlemons Q || 50 Adapted from Varian, Intermediate Microeconomics, 7th ed., 695 – 696. His example is itself an adaptation from a famous paper by George Akerlof, “The Market for Lemons: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 84 (1970): 485 – 500. Markets with asymmetric information General categories of problems of asymmetric information: Adverse Selection: A situation in which individuals possess hidden information, leading to a market selection process that results in a pool of individuals with economically undesirable characteristics. Moral Hazard: A situation in which one party to a contact takes a hidden action that creates benefits at the expense of another party to the contract. Social institutions that help solve these market inefficiencies: Private agent responses to problems of asymmetric information: Signaling – the party possessing private information takes action to generate a credible signal. Screening – the party with imperfect information takes action to induce a advantageous sorting of the market. Public / Private sector responses to problems of asymmetric information: Compulsory purchase plans (insurance markets) Licensing and certification (note that this may also be done by private agents). Market regulation, including “truth” laws and “insider trading” laws. Agency costs What is the “agency problem” and what are agency costs? Efficiency costs which arise when there is a divergence of interests between parties to a transaction. When one party to a transaction cannot observe the effort of another party, upon whose effort the value of the transaction depends, we say there is a principal-agent problem. Examples: • Shareholders (principal) cannot perfectly monitor the efforts of a CEO (agent) • CEO (principal) cannot perfectly monitor the efforts of managers (agent) In such cases, the principal cannot determine whether a bad outcome was the result of the agent’s low effort or due to bad luck. Agency costs and Governance of Economic Transactions What is the “agency problem” and what are agency costs? “In the absence of agency problems, all individuals associated with an organization can be instructed to maximize profit or net market value or to minimize costs. Individuals will be prepared to carry out their instructions since they do not care per se about the outcome of the organization’s activities. Effort and other types of costs can be reimbursed directly and so incentives are not required to motivate people. Also no governance structure is require to resolve disagreements, since there are none.” Oliver Hart, “Corporate Governance: Some Theory and Implications.” The Economic Journal 105 (May 1995): 678 – 689.. Basic Principal-Agent Model Principal’s Share Uncertainty Observable Outcome Payoffs Agent’s Share Agent’s Actions Contract The Agency Challenge. To structure a contract that specifies division of payoffs in such a way that the agent’s actions will maximize those payoffs, given two complicating factors: Uncertainty Unobservability of effort The “Canonical” Agency Model Assumptions 1. An interdependent relationship between a principal and an agent in which there is goal conflict. In terms of behavior motives, the utility of the principal is contingent upon a strategic choice by the agent. 2. The principal is risk neutral, i.e. his utility function is linear with respect to his source of income (profits), which are influenced by the effort of the agent and subject to uncertainty. V x is the market value of output, x x f e, , where e is the effort level of the agent, is uncertainty U P x, w V x w, where w is the wage payment (variable cost) 3. The agent is risk averse, i.e. his utility function is convex with respect to his source of income (wages), and he experiences disutility from effort. dU d 2U U A w, e U w e, where U w is the utility deriving from wages, w, dw 0, dw 2 0 e is the agent' s effort level 4. The agent has an outside opportunity (reservation wage), U A . The “Canonical” Agency Model Illustrative Example 1. V x 10,30, e 0,1 2. ~ e 0 23 , 13 ; e 1 13 , 23 pr ( x) 23 ,V x 10 If e 0 EV x 16.67 1 pr ( x) 3 ,V x 30 pr ( x) 13 ,V x 10 If e 1 EV x 23.33 2 pr ( x ) , V x 30 3 3. U A w, e w e, and U A 1 4a. Scenario 1: Agent’s effort is directly observable by the principal. The principal establishes w at the minimum level required to induce e = 1 (A level that will generate utility for the agent equal to their reservation utility). Select w s.t. U A w 1 1 w 4 The utility-generating properties of this outcome (“First Best”): U P 23.33 4 19.33; U A 4 1 1; U 20.33 P, A The “Canonical” Agency Model Illustrative Example (continued) 4b. Scenario 2: Agent’s effort is not directly observable by the principle. Principal makes w contingent upon V x ; agent chooses e based on expected utility, E U A w, e . Define outcome-contingent wage rates as w30 if V x 30 and w10 if V x 10 . To induce e = 1, the principal’s offer must satisfy two constraints: (1) Incentive compatibility constraint. 2 3 E U A w, e 1 E U A w, e 0 w30 1 13 w10 1 1 3 w30 2 3 w10 w30 9 w10 The wage associated with high effort must “sufficiently” exceed the wage from low effort. (2) Individual participation constraint. 2 3 E U A w, e 1 U A w30 1 13 w10 1 1 4 w30 w10 36 The expected wage must exceed the agent’s reservation wage. The optimal contract from the principal’s perspective is w30 9; w10 0. The utility-generating properties of this outcome (“Second Best”): E U P E V x w 23 30 9 13 10 0 17.33 E U A e 1 9 1 2 3 1 3 EU 18.33 P, A 0 1 1 The “Canonical” Agency Model Summary Inability to observe effort entails efficiency costs (in terms of lower utility or surplus generated from the transaction. The difference in utility outcomes may be interpreted as the cost of inducing a risk-averse agent to accept some risk There is an implicit tradeoff between efficient risk bearing and creation of incentive effects.