Stroop Task

advertisement

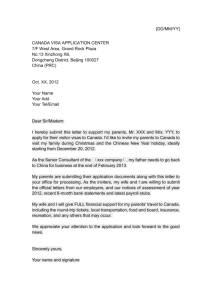

Cognition-emotion interactions Lecture # 5: October 13, 2004 Important issues to consider • The nature of the task being performed • Personal relevance • Mode (functional) versus Node (spreading activation) theories of cognition-emotion interactions • The relationship between depression / anxiety and basic emotions such as sadness / fear from which research findings are extrapolated. • Automatic versus strategic processing (implicit versus explicit memory). • Trait versus state variables Experimental Tasks • • • • • • Dot localization task Stroop task and modified Stroop Lexical decision task Free recall- explicit memory Word stem/fragment completion- implicit Masked Stroop Dot localization experiment • Simultaneous display of one threatening word and one neutral word on the computer screen. • Anxious subject are quicker to respond to the dot when it is presented in a location previously occupied by a threatening word. • Anxious subjects preferentially attend to cues related to threat, and interpret ambiguous information as threatening. • Inference: subject was more likely to be attending to the threatening word on the previous trial. Dot Localization Stroop task • Stroop (1935) first demonstrated the effect in which participants are slowed to name the ink colour of words that are themselves the names of colours, if the colour name and the ink colour are incongruent compared to a condition in which they are congruent, or compared to a condition in which the ink of regular words or colour patches is named. Stroop Task: Colour naming XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX Stroop Task: Incongruent Green Blue Red Black Blue Red Green Blue Red Black Blue Red Green Red Red Blue Green Black Green Blue Red Black Red Blue Green Red Green Blue Modified (Emotional) Stroop • Participants must name the colour of ink of ordinary words, or threat words related to the source of their anxiety • For example Foa et al. (1991) had people with PTSD colour name words related to the source of their trauma. – Slowed more to trauma-related words – Those who coped better showed less interference Lexical decision task • Subjects must decide whether words presented are valid examples of English words, or whether they are nonwords (that follow the rules of pronunciation within the English language). • Has been used to show ‘positive priming effects’. For instance, subjects would be faster to say that ‘doctor’ is a word after seeing the related word ‘nurse’ than after seeing the unrelated word ‘forest’. – Automatic spreading of activation through a semantic network Personal Relevance • Depressed subjects selectively recall negative information only when it has been encoded in relation to themselves. For example, Bradley & Mathews (1983) found that depressed subjects recall more negative trait adjectives when they have been asked whether those adjectives describe themselves, compared to when they must make the judgment of whether they describe another person. • Similarly, Butler & Mathews (1983; 1987) found that anxious subjects rate the probability of negative events happening to them in the future higher than non-anxious subjects do, but not the probability of negative events happening to another person (Personal Optimism Scale). Personal Relevance (con’t) • On the modified Stroop task, subjects are slowed most in their colour naming performance when to-be-ignored words match their current concerns: – – – – – – Physical threats = “disease” or “fatal” Social threats = “foolish” or “lonely” Panic disorder = physical symptoms or catastrophic disease Social phobics = socially threatening words Eating disorders = food-related words PTSD = words related to the particular trauma (also, those who coped better showed less interference). • Thus, emotionally selective processing is confined to material that matches individuals’ current concerns (i.e., personal relevance). Bower’s Network Theory • Emotions are represented as nodes in a memory network, and vary on the basis of the content of the information attached to that node. • Information and experiences acquired in a particular emotional state are connected in a memory network. • When an emotional representation is activated in memory, there is a spreading of activation to all other information that was acquired in the same emotional state. Problems with Network / Node Theories • Difficult to show state-dependent memory effects. • Mood-incongruent recall has sometimes been found. • Failure to find effects on lexical decision tasks A mode theory: Oatley and Johnson-Laird’s Communicative theory (1988; 1995) • There are a limited number of basic emotions representing solutions to problems of adaptation that have been incorporated into our nervous systems through evolution because they are functional and have consequences that are better than acting randomly, or not acting at all. Emotions are ‘heuristics’. • The elicitation of emotion imposes a particular mode of organization on the nervous system, consistent with the function of that particular emotion. This simplifies and specializes us to respond to a personally-relevant event or stimulus in our environment in an adaptive manner. • Is a goal-relevance theory of emotion… why? Evidence to support mode theories • Lexical decision task: Emotionally congruent effects when two words are presented, but not with single words – Competition for resources – Processing priority • Differential effects of anxiety and depression on measures of attention and memory – Selective attention to threatening material is a robust effect that has been shown across several different tasks. – Depressed patients recall more negative words related to themselves, but mood-congruent recall is rarely seen in studies of anxious subjects. Evidence to support mode theories • Anxiety and Depression have differential effects on measures of implicit and explicit memory – Completions by anxious patients more likely to match previously encountered threatening words, while recovered and normals show reverse trend. When asked to use stem to recall words, no group differences (Mathews et al., 1989). – In contrast, depressed patients show greater explicit recall of negative words, but do not differ from normals in their completions • Masked Stroop – Interference effects found only in the group of anxious subjects for threat words relevant to the concerns of either anxious or depressed subjects. • Automatic and preattentive processes that are relatively crude and involve only the classification of stimuli into ‘threat’ and ‘non-threat’ categories (doesn’t this sound like Caccioppo’s Rudimentary Stimulus Evaluation?) • Function of fear / anxiety: to identify and avoid danger – Best served by rapid perceptual encoding of threatening information, and this is why selective attention and implicit memory effects are found • Function of sadness / depression: – Elaborative processing of negative personal information… loss of goal… re-evaluation of personal concerns • Retrospective memory: Previous coping strategies? Remember events that led up to the demise for comprehension? Put the loss in context? Sadness Fear Assumption re: Emotion and psychopathology (on a continuum) • The research presented by Mathews and colleagues assumes a continuum between basic emotions and emotional disorders. – Sadness Depression Fear Anxiety • This is not necessarily warranted given the fact that psychopathological conditions are characterized by various cognitive and somatic phenomena that are beyond what is experienced as part of an emotion episode, from which results are being extrapolated from. – For example, depression involves feelings of guilt, hopelessness, loss of appetite, sleep disturbance among other symptoms. Counterevidence • Niedenthal and Setterlund (1994) induced happy and sad moods by playing music throughout an experimental session (Adagietto by Mahler; Vivaldi Concerto in C Major). • Lexical decision task: Happy words, generic positive words, sad words, generic neutral words, and neutral words. • When listening to happy music, subjects were faster to identify happy than sad words, and vice-versa. These effects did not hold for generic positive and negative words. • What evidence presented earlier in the lecture does this conflict with? • What are the implications of the evidence presented above? • Baron (1987) brought pairs of people of the same sex in to the laboratory together for a study in impression formation (one participant was actually a confederate of the experimenter). • Subject was ‘randomly’ chosen as an interviewer in a practice interview for a job as a management trainee. • While the accomplice ‘studied’ the interview questions, the subject was induced into either a happy or sad emotional state by receiving false feedback with regards to performance on a task they were given to perform. • Interviewer had to ask a set of six prearranged questions and the responses were prearranged but mixed in valence. – E.g. ‘What are your most important traits’? Answer: On the positive side, I am ambitious, reliable, friendly, but on the negative side my friends tell me that I am stubborn, and I know I am impatient and pretty disorganized”. • Results: Interviewers induced into a happy mood were more likely say that they would hire the job candidate, and in general rated them more positively. • Interviewers were also asked to recall the things that the job candidates had said about themselves. • Interviewers that had been induced into a positive mood recalled more positive traits about the job candidate, and fewer negative traits, and vice versa. • Which phenomenon described earlier in the lecture does this result contradict ? Baron (1987) Emotional vulnerability • Comes from a ‘Stress-Diathesis’ model of psychopathology. • Mathews and colleagues believe that the tendency to selectively encode threatening cues when under stress represents the cognitive substrate for vulnerability to anxiety states. • MacLeod and Matthews (1988) using the dot localization task found that high-anxious subjects became more attentive to threatening words just before an important examination than did low trait-anxious subjects. • Thus, only high trait anxiety subjects reacted to stress by selectively attending to information likely to worsen their emotional state ??? • Question: is selectively attending to cues that are related to the source of the threat dysfunctional ? We are talking about traitanxious subjects, not anxiety-disordered subjects. – According to Salovey and Mayer (1990), some people use emotion (even fear and anxiety) instrumentally– e.g. to motivate themselves. • ‘If it weren’t for the last minute, nothing would get done’? Strategic control: Overriding automatic processing biases associated with emotion • Mathews & Sebastian: Selected students with low or high selfreported fear of snakes and conducted the modified Stroop task. • Emotion induction: Subjects were shown a small boa in a tank and were told that they would have to approach it. No significant differences, in fact a trend in the opposite direction. Contrary to results presented earlier. • Pre-attentive detection of threatening stimuli can be opposed by inattention or selective ignoring at a post-awareness stage. • Similar to the idea of secondary appraisals (Lazarus)