'Best Practice' in Police Training? J. Francis-Smythe

advertisement

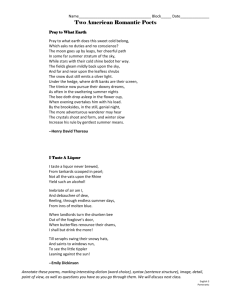

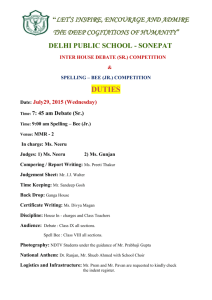

‘Best Practice’ in Police Training? J. Francis-Smythe, University College Worcester http://www.worc.ac.uk/ INTRODUCTION FINDINGS “Methodologies have been proposed for systematically and scientifically guiding the training process. Despite the potential benefits of this knowledge base, however, a distressing gap still exists between the scholarly work and the actual conduct of training in organisations.” Dipboye (1997, p.31) AT THE ORGANISATIONAL LEVEL This research attempts to assess the extent to which this statement is true for police training in the UK. A simplified version of the ‘Training Wheel’ (Figure 1) proposed by Bee and Bee (1995, p.xvi) is the systems approach framework used in this research. This poster reports on the methodology employed for the whole study but focuses specifically on the findings with respect to identifying training needs. In a survey carried out as part of the Price Waterhouse Cranfield Project in 1992, Holden and Livian showed that nearly a quarter of ‘good practice’ organisations in the UK, and nearly half in Germany did not do any systematic training needs analysis. The favoured method of assessment varied from country to country, France, Italy and the Netherlands preferring ‘analysis of business plans’, Sweden and the UK performance appraisal and Switzerland, Denmark and Spain, line manager requests. So how does UK Police training compare? The Present research uses three level indicators to indicate the level at which a need has been identified, the individual, group or whole organisation. The literature suggests a number of sources of information in an organisation which may help with the identification of training needs. Typically, Bee and Bee (1995) suggest human resource planning (HR), succession planning (SP), critical incidents (CI), management information systems (MIS) and performance appraisal systems (PA). The extent to which some or all of these sources of information are used in analysing needs from each of the three levels in Police Forces is analysed. Business Needs Figure 1. A number of Forces have Training Strategy panels with representatives from each of the key areas of the Force who identify corporate training issues. This seems most effectively monitored in those forces with a formal Project Management system which enables Heads of Training to monitor training applications in large corporate projects before they are commissioned, requiring all stakeholders to sign support, thus minimising un-planned training needs. AT THE OCCUPATIONAL LEVEL Very few Forces appear to have systematically carried out role-based training needs analyses, a few have sought to identify the training needs of some specific roles (HR) (e.g. control room operators, Geographic Inspectors) but only one was identified to have implemented a large-scale (12 - 25 roles) needs analysis. Similarly, the methodology employed has varied from a single questionnaire approach to job incumbents asking them to rate themselves against a list of required skills and hence identifying an overall skills gap, to the determination of role-specific training needs on the basis of ‘the professional judgement of key senior people’, through to a full extensive focus group/interview, observation and survey program at a 360 degree level. AT THE INDIVIDUAL LEVEL Evaluation Training Delivery Training Needs Analysis (TNA) Training Design Planning and Development Most Forces identify individual training needs at appraisal interviews (PA), which are generally annual, although one Force identified ran them 3-monthly. The Home Office developed a Performance Development Review (PDR) system in 1996 based on 9 Police competencies which most Forces are now in the process of implementing; a few across the whole Force, officers and support staff alike. From the analysis it would appear that as with other major UK organisations (Holden & Livian, 1992) Performance Appraisal is the main source of information for training needs analysis in the Police Service but that increasingly Human Resource Planning and Management Information Systems are guiding the process. Succession planning input is still relatively rare. The research would also appear to support the concerns of Bee and Bee (1995), cited earlier, that the quality of the information gained (with respect to training needs) is very dependent on the quality of the systems. There appears to be a general concern that whilst the formal systems may be in place, the training, development, monitoring and evaluation issues they present have still to be addressed. REFERENCES METHOD Bee, F. & Bee, R. (1995). Training Needs Analysis and Evaluation. Institute of Personnel and Development. Phase 1 - Eight Police Forces identified as exhibiting ‘good practice’ in training in a survey by the Police Research Group (RPG) in 1997 participated in the first phase. Taped interviews with key personnel took place on-site over a period ranging from 1.5 hours to 6 hours. Transcription of the tapes and thematic analysis of the data gave rise to a series of themes. Dipboye, R L. (1997) Organisational Barriers to Implementing a Rational Model of Training. In Quinones, M.A. & Ehrenstein, A. Training For a Rapidly Changing Workplace. American Psychological Association, Washington. Phase 2 - A national survey of all Forces (n=47) asked police training departments to identify any innovative measures they had taken over the last 12 months in order to increase the effectiveness of training. The survey used the themes as prompts. Response rate was 26%. Of this 26%, 40% were contacted by phone for further details. Data from the interviews and open survey responses were content analysed and categorised according to the framework of Training Wheel. Holden, L. & Livian, Y. (1992). Does strategic training policy exist? Some evidence from ten European countries. Personnel Review, 21, 1, 12 - 23.