Lesson 7

advertisement

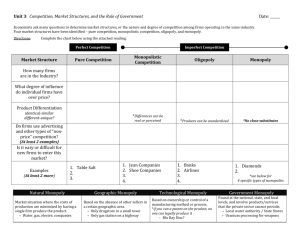

THE NATURE OF INDUSTRY INTRODUCTION • Several factors affect decisions such as how much to produce, what price to charge, how much to spend on R&D, advertising etc. • No single theory or methodology provide managers answers to these questions • Pricing strategy/ advertising etc. for a car maker will differ from food manufacturers • In this section we examine the important differences that exists among industries. Approaches to Studying Industry • The Structure-Conduct-Performance (SCP) Paradigm: • Different structures lead to different conducts and different performances Market Structure Refers to factors such as 1. The number of firms that compete in a market, 2. The relative size of the firm (concentration) 3. Technological and cost conditions 4. Ease of entry or exit into industry Different industries have different structures that affect managerial decision making (Structural differences) 1. Firm Size: Some industries naturally give rise to large firms than do other industries: e.g. Industry = Aerospace, Largest firm = Boeing Industry = Computer, office equipment Largest firm = IBM 2. Industry concentration: Are there many small firms or only a few large ones? (competition or little competition?) 2 ways to measure degree of concentration: a. Concentration ratios b. Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) Concentration ratios measure how much of the total output in an industry is produced by the largest firms in that industry. Most common one used is the four-firm concentration ratio (C4) = the fraction of total industry sales produced by the 4 largest firms in the industry If industry has very large number of firms, each of which is small, then is close to 0 When 4 or fewer firms produce all of industry output, is close to 1 • Four-Firm Concentration Ratio – The sum of the market shares of the top four firms in the defined industry. Letting Si denote sales for firm i and ST denote total industry sales Si C4 w1 w2 w3 w4 , where w1 ST – The closer C4 is to zero, the less concentrated the industry . e.g. Industry has 6 firms. Sales of 4 firms = $10 and $5 for the other 2. ST = 50 C4 = 40/50 = 0.8 4 largest firms account for 80% of total industry output • Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) – The sum of the squared market shares of firms in a given industry, multiplied by 10,000 (to eliminate decimals): – By squaring the market shares, the index weights firms with high market shares more heavily – HHI = 10,000 S wi2, where wi = Si/ST. 0 <= HHI <= 10,000 Closer to 0 means industry has numerous infinitesimally small firms. Closer to 10,000 means little competition HHI example 3 firms in an industry. 2 have sales of $10 each and the other with $30 sales. Total Industry Sales = $50 30 2 10 2 10 2 HHI 10000 4400 50 50 50 C4 1 Since the top three firms account for all industry sales Limitation of Concentration Measures • Market Definition: National, regional, or local? • Global Market: Foreign producers excluded. • Industry definition and product classes. • Market Definition: National, regional, or local? If there are 50 same size gas stations in the US, one in each state, each firm will have 1/50 market share. C4 = 4/50 market for gas is not highly concentrated. What good is this to a consumer in Blaine, Washington, since the relevant market is her local market? • Geographical differences among markets lead to biases in concentration measures Global Market: Foreign producers excluded. This tends to overstate the true level of concentration in industries in which significant number of foreign producers serve the market e.g. C4 for beer producers in US = 0.9 but this ignores the beer produced by many breweries in Mexico, Canada, Europe etc. The C4 based on both imported and domestic beer would be considerably lower Industry definition and product classes: There is considerable aggregation across product classes. e.g. Soft drink industry is dominated by Pepsi and Coca-Cola yet the C4 for 2004 is 47%. Quite low. The C4 contains many types of bottled and canned drinks including lemonade, iced tea, fruit drinks etc. 3. TECHNOLOGY • Some industries are labor intensive while others are capital intensive • In some industries, firms have access to identical technologies and therefore similar cost structures • In others, only 1 or 2 firms may have superior technology giving them cost advantages over others • Those with superior technology will completely dominate the industry 4. Demand and Market Conditions • Markets with relatively low demand will be able to sustain only few firms • Access to information vary from industry to industry • Elasticity of demand for products tend to vary from industry to industry • Elasticity of demand for a firm’s product may differ from the market elasticity of demand for the product Markets where there are no close substitutes for a given firm’s product, elasticity of demand for the firm’s product will be close to that of the market Rothschild Index = R =Et/Ef Et = market elasticity Ef = firm’s elasticity Measures how sensitive a firm’s demand is relative to the entire market. When industry has many firms each producing a similar product, R will be close to zero 5. Potential for Entry Easier for new firms to enter some industries than other industries. Barriers to entry: • Explicit cost of entering (Capital requirements • Patents • Economies of scale: new firms cannot generate enough volume to reduce average cost CONDUCT: Conduct (behavior) of firms differ across industries 1. Some industries charge a higher markup than others. (pricing behavior) 2. Some industries are more susceptible to mergers or takeovers 3. Amount spent on R&D tend to vary across industries 1. Pricing behavior: Lerner Index (L) = (P – MC)/P Gives how firms in an industry mark up their prices over MC. If firms vigorously compete, L is close to zero. P = (1/1-L)MC When L=2 firms charge price that is 2x the MC of production e.g Tobacco industry. L = 76% P is 4.17x the actual MC of production Lerner Indices & Markup Factors Industry Food Tobacco Textiles Apparel Paper Chemicals Petroleum Lerner Index 0.26 0.76 0.21 0.24 0.58 0.67 0.59 Source: Baye and Lee, NBER working paper # 2212 Markup Factor 1.35 4.17 1.27 1.32 2.38 3.03 2.44 2. Integration and Merger Activity Uniting productive services. Can result from an attempt by firms to • Reduce transaction cost • Reap the benefits of economies of scale and scope • Increase market power • Gain better access to capital markets 3 types of integration: Vertical Integration: Various stages in the production of a single product are carried out by a single firm e.g. Car manufacturer produces its own steel, uses the steel to make car bodies and engines. Reduces transaction cost Horizontal Integration: Merging production of similar products into a single firm e.g. 2 banks merge to form one firm to enjoy cost savings of economies or scale or scope and enhance market power. When social benefits of this merger is relatively small compared to social cost of concentrated industry, government may block this type of merger US Department of Justice considers industries with HHI > 1800 to be highly concentrated and may block any merger that will increase the HHI by more than 100 HHI < 1000 are considered unconcentrated. 3. Conglomerate Mergers Integrating different product lines into a single firm Cigarette maker acquires a bread manufacturing firm. This is to reduce the variability of firm’s earnings due to demand fluctuations and to enhance the firm’s ability to raise funds in the capital market Performance • Performance refers to the profits and social welfare that result in a given industry. • Social Welfare = CS + PS – Dansby-Willig Performance Index measure by how much social welfare would improve if firms in an industry expanded output in a socially efficient manner. Approaches to Studying Industry • The Structure-Conduct-Performance (SCP) Paradigm: Causal View Market Structure Conduct Performance e.g. Consider a highly concentrated industry. This structure gives market power enabling them to charge higher prices for their products. This conduct (behavior of charging higher prices ) is caused by the market structure (few competitors). The high prices cause higher profits and poor performance (low social welfare) Thus, a concentrated market causes high prices and poor performance • The Feedback Critique – No one-way causal link. – Conduct can affect market structure. – Market performance can affect conduct as well as market structure. Managing in Competitive, Monopolistic, and Monopolistically Competitive Markets Learning Objectives • Describe the key characteristics of the four basic market types used in economic analysis. • Compare and contrast the degree of price competition among the four market types. • Provide specific actual examples of the four types of markets. • Explain why the P=MC rule leads firms to the optimal level of production. Learning Objectives • Describe what happens in the long run in markets where firms that are either incurring economic losses or are making economic profits. Explain why this happens with particular attention to the key assumptions used in this analysis. • Explain how and why the MR=MC rule helps a monopoly to determine the optimal level of price and output. • Explain the relationship between the MR=MC rule and the P=MC rule. Learning Objectives • Cite the main differences between monopolistic competition and oligopoly • Describe the role that mutual interdependence plays in setting prices in oligopolistic markets • Illustrate price rigidity in oligopoly markets using the “kinked demand curve” • Elaborate on how non-price factors help firms in monopolistic competition and oligopoly to differentiate their products and services • Cite and briefly describe the five forces in Porter’s model of competition Four Basic Market Types 1. Perfect Competition (no market power) – Large number of relatively small buyers and sellers – Standardized product – Very easy market entry and exit – Nonprice competition not possible 2. Monopoly (absolute market power subject to government regulation) – One firm, firm is the industry – Unique product or no close substitutes – Market entry and exit difficult or legally impossible – Nonprice competition not necessary 3. Monopolistic Competition (market power based on product differentiation) – Large number of relatively small firms acting independently – Differentiated product – Market entry and exit relatively easy – Nonprice competition very important 4. Oligopoly (market power based on product differentiation and/or the firm’s dominance of the market) – – – – Small number of relatively large firms that are mutually interdependent Differentiated or standardized product Market entry and exit difficult Nonprice competition very important among firms selling differentiated products Pricing and Output Decisions in Perfect Competition • The Basic Business Decision: entering a market on the basis of the following questions: – How much should we produce? – If we produce such an amount, how much profit will we earn? – If a loss rather than a profit is incurred, will it be worthwhile to continue in this market in the long run (in hopes that we will eventually earn a profit) or should we exit? Unrealistic? Why Learn? • Many small businesses are “price-takers,” and decision rules for such firms are similar to those of perfectly competitive firms. • It is a useful benchmark. • Explains why governments oppose monopolies. • Illuminates the “danger” to managers of competitive environments. – Importance of product differentiation. – Sustainable advantage. • Key assumptions of the perfectly competitive market – The firm operates in a perfectly competitive market and therefore is a price taker. – The firm makes the distinction between the short run and the long run. – The firm’s objective is to maximize its profit in the short run. If it cannot earn a profit, then it seeks to minimize its loss. – The firm includes its opportunity cost of operating in a particular market as part of its total cost of production. Setting Price $ $ S Pe Df D QM Market Firm Qf Profit-Maximizing Output Decision • MR = MC. • Since, MR = P, • Set P = MC to maximize profits. Graphically: Representative Firm’s Output Decision Profit = (Pe - ATC) Qf* MC $ ATC AVC Pe = Df = MR Pe ATC Qf* Qf A Numerical Example • Given – P=$10 – C(Q) = 5 + Q2 • Optimal Price? – P=$10 • Optimal Output? – MR = P = $10 and MC = 2Q – 10 = 2Q – Q = 5 units • Maximum Profits? – PQ - C(Q) = (10)(5) - (5 + 25) = $20 • The firm incurs a loss. At the optimum output level price is below average cost. • However, since price is greater than average variable cost, the firm is better off producing in the short run, because it will still incur fixed costs greater than the loss. Should this Firm Sustain Short Run Losses or Shut Down? Profit = (Pe - ATC) Qf* < 0 ATC MC $ AVC ATC Pe Loss Pe = Df = MR Qf* Qf Shutdown Decision Rule • A profit-maximizing firm should continue to operate (sustain shortrun losses) if its operating loss is less than its fixed costs. – Operating results in a smaller loss than ceasing operations. • Decision rule: – A firm should shutdown when P < min AVC. – Continue operating as long as P ≥ min AVC. • Contribution Margin (CM): the amount by which total revenue exceeds total variable cost. • CM = TR – TVC • If the contribution margin is positive, the firm should continue to produce in the short run in order to defray some of the fixed cost. • Shutdown Point: the lowest price at which the firm would still produce. • At the shutdown point, the price is equal to the minimum point on the AVC. This is where selling at the price results in zero contribution margin. • If the price falls below the shutdown point, revenues fail to cover the fixed costs and the variable costs. The firm would be better off if it shut down and just paid its fixed costs. Firm’s Short-Run Supply Curve: MC Above Min AVC ATC MC $ AVC P min AVC Qf* Qf Short-Run Market Supply Curve • The market supply curve is the summation of each individual firm’s supply at each price. P Firm 1 Market Firm 2 P P S1 S2 SM 15 5 10 18 Q 20 25 Q 30 43Q Long Run Adjustments? • If firms are price takers but there are barriers to entry, profits will persist. • If the industry is perfectly competitive, firms are not only price takers but there is free entry. – Other “greedy capitalists” enter the market. Effect of Entry on Price? $ $ S Entry S* Pe Pe* Df Df* D QM Market Firm Qf Effect of Entry on the Firm’s Output and Profits? MC $ AC Pe Df Pe* Df* QL Qf* Q Summary of Logic • Short run profits leads to entry. • Entry increases market supply, drives down the market price, increases the market quantity. • Demand for individual firm’s product shifts down. • Firm reduces output to maximize profit. • Long run profits are zero. Features of Long Run Competitive Equilibrium • P = MC – Socially efficient output. • P = minimum AC – Efficient plant size. – Zero profits • Firms are earning just enough to offset their opportunity cost. • In the long run, the price in the competitive market will settle at the point where firms earn a normal profit. – Economic profit invites entry of new firms which shifts the supply curve to the right, puts downward pressure on price and reduces profits. – Economic loss causes exit of firms which shifts the supply curve to the left, puts upward pressure on price and increases profits. • Observations in perfectly competitive markets: – The earlier the firm enters a market, the better its chances of earning above-normal profit (assuming a strong demand in the market). – As new firms enter the market, firms that want to survive and perhaps thrive must find ways to produce at the lowest possible cost, or at least at cost levels below those of their competitors. – Firms that find themselves unable to compete on the basis of cost might want to try competing on the basis of product differentiation instead. Monopoly Environment • Single firm serves the “relevant market.” • Most monopolies are “local” monopolies. • The demand for the firm’s product is the market demand curve. • Firm has control over price. – But the price charged affects the quantity demanded of the monopolist’s product. “Natural” Sources of Monopoly Power • Economies of scale • Economies of scope • Cost complementarities “Created” Sources of Monopoly Power • Patents and other legal barriers (like licenses) • Tying contracts • Exclusive contracts Contract... • Collusion I. II. III. Managing a Monopoly • Market power permits you to price above MC • Is the sky the limit? • No. How much you sell depends on the price you set! A Monopolist’s Marginal Revenue P 100 TR Unit elastic Elastic Unit elastic 1200 60 Inelastic 40 800 20 0 10 20 30 40 50 Q 0 10 20 30 40 MR Elastic Inelastic 50 Q Monopoly Profit Maximization Produce where MR = MC. Charge the price on the demand curve that corresponds to that quantity. MC $ ATC Profit PM ATC D QM MR Q Useful Formulae • What’s the MR if a firm faces a linear demand curve for its product? P a bQ MR a 2bQ, where b 0. • Alternatively, 1 E MR P E A Numerical Example • Given estimates of • P = 10 - Q • C(Q) = 6 + 2Q • Optimal output? • • • • MR = 10 - 2Q MC = 2 10 - 2Q = 2 Q = 4 units • Optimal price? • P = 10 - (4) = $6 • Maximum profits? • PQ - C(Q) = (6)(4) - (6 + 8) = $10 Long Run Adjustments? • None, unless the source of monopoly power is eliminated. Why Government Dislikes Monopoly? • P > MC – Too little output, at too high a price. • Deadweight loss of monopoly. Deadweight Loss of Monopoly $ MC Deadweight Loss of Monopoly ATC PM D MC QM MR Q Arguments for Monopoly • The beneficial effects of economies of scale, economies of scope, and cost complementarities on price and output may outweigh the negative effects of market power. • Encourages innovation. Monopoly Multi-Plant Decisions • Consider a monopoly that produces identical output at two production facilities (think of a firm that generates and distributes electricity from two facilities). – Let C1(Q2) be the production cost at facility 1. – Let C2(Q2) be the production cost at facility 2. • Decision Rule: Produce output where MR(Q) = MC1(Q1) and MR(Q) = MC2(Q2) – Set price equal to P(Q), where Q = Q1 + Q2. Monopolistic Competition: Environment and Implications • Numerous buyers and sellers • Differentiated products – Implication: Since products are differentiated, each firm faces a downward sloping demand curve. • Consumers view differentiated products as close substitutes: there exists some willingness to substitute. • Free entry and exit – Implication: Firms will earn zero profits in the long run. Managing a Monopolistically Competitive Firm • Like a monopoly, monopolistically competitive firms – have market power that permits pricing above marginal cost. – level of sales depends on the price it sets. • But … – The presence of other brands in the market makes the demand for your brand more elastic than if you were a monopolist. – Free entry and exit impacts profitability. • Therefore, monopolistically competitive firms have limited market power. Competing in Imperfectly Competitive Markets • Non-price variables: any factor that managers can control, influence, or explicitly consider in making decisions affecting the demand for their goods and services. – – – – – – – – – Advertising Promotion Location and distribution channels Market segmentation Loyalty programs Product extensions and new product development Special customer services Product “lock-in” or “tie-in” Pre-emptive new product announcements Marginal Revenue Like a Monopolist P 100 TR Unit elastic Elastic Unit elastic 1200 60 Inelastic 40 800 20 0 10 20 30 40 50 Q 0 10 20 30 40 MR Elastic Inelastic 50 Q Monopolistic Competition: Profit Maximization • Maximize profits like a monopolist – Produce output where MR = MC. – Charge the price on the demand curve that corresponds to that quantity. Short-Run Monopolistic Competition MC $ ATC Profit PM ATC D QM MR Quantity of Brand X Long Run Adjustments? • If the industry is truly monopolistically competitive, there is free entry. – In this case other “greedy capitalists” enter, and their new brands steal market share. – This reduces the demand for your product until profits are ultimately zero. Long-Run Monopolistic Competition Long Run Equilibrium (P = AC, so zero profits) $ MC AC P* P1 Entry MR Q1 Q* MR1 D D1 Quantity of Brand X Monopolistic Competition The – The – – Good (To Consumers) Product Variety Bad (To Society) P > MC Excess capacity • Unexploited economies of scale The Ugly (To Managers) – P = ATC > minimum of average costs. • Zero Profits (in the long run)! Optimal Advertising Decisions • Advertising is one way for firms with market power to differentiate their products. • But, how much should a firm spend on advertising? – Advertise to the point where the additional revenue generated from advertising equals the additional cost of advertising. Optimal Advertising Decisions – Equivalently, the profit-maximizing level of advertising occurs where the advertising-to-sales ratio equals the ratio of the advertising elasticity of demand to the own-price elasticity of demand. EQ , A A R EQ , P Maximizing Profits: A Synthesizing Example • C(Q) = 125 + 4Q2 • Determine the profit-maximizing output and price, and discuss its implications, if – You are a price taker and other firms charge $40 per unit; – You are a monopolist and the inverse demand for your product is P = 100 - Q; – You are a monopolistically competitive firm and the inverse demand for your brand is P = 100 – Q. Marginal Cost • C(Q) = 125 + 4Q2, • So MC = 8Q. • This is independent of market structure. Price Taker • MR = P = $40. • Set MR = MC. • 40 = 8Q. • Q = 5 units. • Cost of producing 5 units. • C(Q) = 125 + 4Q2 = 125 + 100 = $225. • Revenues: • PQ = (40)(5) = $200. • Maximum profits of -$25. • Implications: Expect exit in the longrun. Monopoly/Monopolistic Competition • MR = 100 - 2Q (since P = 100 - Q). • Set MR = MC, or 100 - 2Q = 8Q. – Optimal output: Q = 10. – Optimal price: P = 100 - (10) = $90. – Maximal profits: • PQ - C(Q) = (90)(10) -(125 + 4(100)) = $375. • Implications – Monopolist will not face entry (unless patent or other entry barriers are eliminated). – Monopolistically competitive firm should expect other firms to clone, so profits will decline over time. Conclusion • Firms operating in a perfectly competitive market take the market price as given. – Produce output where P = MC. – Firms may earn profits or losses in the short run. – … but, in the long run, entry or exit forces profits to zero. • A monopoly firm, in contrast, can earn persistent profits provided that source of monopoly power is not eliminated. • A monopolistically competitive firm can earn profits in the short run, but entry by competing brands will erode these profits over time. Oligopoly • Oligopoly is a market dominated by a relatively small number of large firms • Products are either standardized or differentiated • Measures of Market Concentration – Herfindahl-Hirschman index (HH): measure of market concentration (max HH = 10,000) n HH S i2 i 1 • n: number of firms in the industry • Si: firm’s market share • Unconcentrated markets have HH < 1,000 Pricing in an Oligopolistic Market: Rivalry and Mutual Interdependence • Mutual Interdependence: relatively few sellers create a situation where each is carefully watching the others as it sets its price. • Kinked Demand Curve Model – Basic Assumption: competitor will follow a price decrease but will not make a change in reaction to a price increase. Pricing in an Oligopolistic Market: Rivalry and Mutual Interdependence • If reduce price and competitors match the price cut then move along more inelastic demand segment Di. • If increase price and competitors do not follow then move along the more elastic segment Df. • Marginal Revenue curve will be discontinuous where the kink occurs (at point A). Competitors do not match price increases Competitors match price cuts • Price Leader: one firm in the industry takes the lead in changing prices. – The price leader assumes that firms will follow a price increase. It assumes that firms may follow a reduction in price, but will not go even lower in order not to trigger a price war. • Non-Price Leader: firm that leads the differentiation of products on other, non-price attributes. • Equalizing at the margin: general economic concept which managers can use to help make an optimal decision. – Can be used to decide the optimal expenditure level of a non-price factor that influences a firm’s demand. – MR = MC is an example of equalizing at the margin. • Revenue and costs may be realized over a long period of time. – Firm must adjust MR, MC for the time value of money.