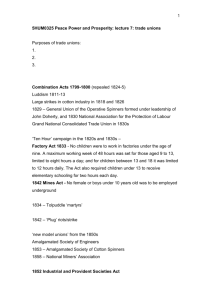

Pulignano_DeFranceschi_Doerflinger

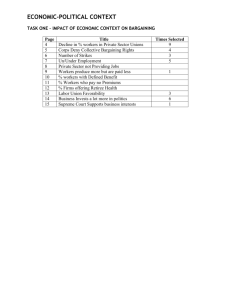

advertisement