File - Brother Murray Hunt

advertisement

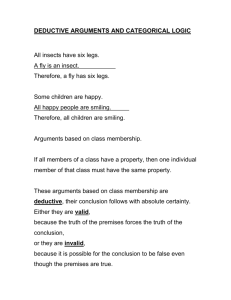

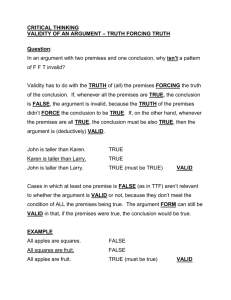

Chapter 1.1 • This chapter may have confused you; • Rather, it was intended to – set forth the concepts of “argument,” “validity” and “soundness,” etc.; – give you an intuitive understanding of those concepts; – persuade you that there must be more systematic ways of testing an argument, especially for validity; and – encourage you, therefore, to anticipate and appreciate the systematic skills yet to be learned. Central concepts • Central concepts – Argument v. non-argument – Deduction v. Induction – Validity & Soundness v. Strength & Cogency Argument • Notion of argument basic to logic • Arguments defined – A group of statements (declarative statements) such that one, a claim (conclusion), is supported by others, reasons (premises). – Conclusion can come anywhere: what is the author’s point? • Declarative statements & rhetorical questions (which can masquerade as declarative statements) • Implicit statements (as opposed to explicit) Analyzing an Argument • Illatives (L. ppl. inferre [illatus] “to infer, inference”) – Conclusion: thus, then, so, therefore, as a result, such that, means that, it can be seen, consequently, hence, we see that, it follows, ergo, etc. – Premise: because, since, when, whenever, if, assume, for, as, for the reason that, etc. • Intellectual charity--helping author to construct argument as intended Non-arguments • Confusion: – Explanations--when truth of conclusion is not in doubt – Conditions--if/then type; may be part of an argument, but are not arguments per se – Analogies--again, may be part of an argument, but are not arguments themselves. • Once an argument has been identified, is it deductive or inductive? • Squishiness (multi-logical); requires context, judgment Distinguishing is a squishy (multi-logical) business: Given truth of premises • Induction – Possible, but unlikely that conclusion is false (contingent*) – If so, called “strong” – Usually moves logically from specific cases to generalization re: those cases* – May include “weasel words” – All appeals to authority, uses of surveys, studies, analogies & types of chicken logic* – Never valid or invalid – All intended to be strong • Deduction – Impossible that conclusion is false (certain*) – If so, called “valid” – Usually moves logically from a general case to more specific case (hence “deduction”)* – May include language of certainty – Virtually all arguments of form “All x are y”* – Never strong or weak – All intended to be valid Deductive arguments are intended to be sound [to succeed] but they may not be [successful]. Deductive arguments may fail [be unsound] for one or both of two reasons: • The arguments themselves are invalid. – I.e., the truth of the premises does not necessarily yield the truth of the conclusion; or, alternatively, even if the premises were true, the conclusion would not “follow” from them. • The premises themselves are false. An argument is • “Valid” if the truth of the premises guarantees the truth of the conclusion (I.e., if the conclusion necessarily follows from the premises--there’s no avoiding it!) • “Invalid” if the premises, whether true or false, cannot guarantee the truth of the conclusion (I.e., the conclusion doesn’t necessarily follow--there are other ways to explain the outcome). Caveats • To say an argument is valid, however, doesn’t mean that it is sound or that it’s conclusion actually is true: – Example: “All dogs are blue animals. All blue animals fly. So, all dogs fly.” • The argument above is valid (if the premises were actually true, it’s conclusion must necessarily follow), but the conclusion is false and the argument is unsound because one or more of the premises is false. Caveats, cont’d. • An argument can have true premises and a true conclusion and still be unsound if it reasons invalidly: – Example: “All dogs are mammals. All terriers are mammals. So, all terriers are dogs.” • All the propositions in the argument above are true, but the truth of the conclusion is only coincidental, and does not necessarily follow from the premises, because the reasoning is invalid (the form of the argument commits a reasoning error called “undistributed middle”--which we’ll learn about later-but can be demonstrated intuitively by substituting “cats” for “terriers” and yielding the conclusion, “All cats are dogs,” clearly a false conclusion). Argument soundness • “Sound” arguments – reason validly from – actually true premises to an – actually true conclusion. • “Unsound” arguments – reason invalidly from premises – whether true or false, or – validly from – untrue premises to conclusion. In either case, “soundness”-or the lack thereof-depends on • The validity (structure) of the reasoning, – Which is relatively easy to test, but may be tricky to grasp & master, and/or • The truth (reliability) of the premises – Which may be difficult to test and master in an infinite universe of propositions. Arguments v. propositions • Arguments are – “Valid” or “invalid” and – “Sound” or “unsound” but – Never “true” or “false.” • Propositions are – “True” or “false” but – Never “valid/invalid” or “sound/unsound” The study of logic, furthermore • is concerned with validity – the form of arguments • as opposed to soundness – [which involves] the truth of propositions [as well as validity] Language of Logic • To help us grasp more easily the concept of validity (the structure of an argument), as opposed to soundness (the truth of the individual propositions), and to be able to study validity better in isolation, logicians frequently cast arguments using – Nonsense words • All mimsies are borogroves . . . – Or symbols • All m are b . . . . • As you can see, in the cases above we aren’t inclined to think about the truth of the propositions, but rather only the structure of the argument. Chapter 1.2: Argument forms • Commercial break • Some deductive arguments take very familiar forms. • • • • • Modus Ponens, aka Affirming the Antecedent Modus Tollens, aka Denying the Antecedent Hypothetical Syllogism Disjunctive Syllogism Constructive Dilemma Forms method • If we can reduce an argument to one of the forms, its validity is very easy to establish. – Simplify – Substitute – Compare Demonstrations • Modus Ponens – aka Affirming Antecedent • Modus Tollens – aka Denying Consequent • Fallacy of Denying Antecedent • Fallacy of Affirming Consequent Chapters 1.3 & 1.4 Preview • Chapter 1.3 – Informal refutation v. proof • Two common fallacious forms • Counterexample method • Categorical statements • Section 1.4 – Induction (v. deduction) • Strength & cogency Chapter 1.3: Testing Deductive Arguments • What are two informal ways of testing deductive arguments? – [Informal] refutation – [Informal] proof Chapter 1.3: Refutation & Proof • What is “refutation”? – A demonstration that, even if premises are true, conclusion is false • Under what conditions will this be successful? – Only if argument is invalid • What is “proof”? – A demonstration of a sequence of individual, logically valid maneuvers from given premises to conclusion • Under what conditions will this be successful? – Only if argument is valid Chapter 1.3: Proof • If an argument cannot be refuted, it may be valid and require proof. • If an argument can be proved, then it is valid and cannot be refuted (although it may still be unsound). • Proof requires a demonstration that, beginning with true premises, a true conclusion necessarily follows through a valid sequence of individual maneuvers. Chapter 1.3: Two Common Fallacious Forms • What five common valid argument forms did we acquire in Chapter 1.2? • What two common fallacious forms did we learn about in Chapter 1.3? • How do we know that they are invalid? Chapter 1.3: The Method of Refutation by Counterexample (Analogous Reasoning) • What is a counterexample? • Why is it called a “counterexample”? – Literally, an analogous example of the argument that runs counter to the claim/conclusion • What is the counterexample method? How is refutation by counterexample done? – Fabricate an analogous scenario in which the premises are true but conclusion is false (the definition of invalidity). ① Substitute variables for statements or terms. ② Substitute new, logically sensitive statements or terms for variables, beginning with a clearly false conclusion. ③ Substitute new logically sensitive statements or terms for corresponding variables to yield clearly true premises. Chapter 1.3: Refutation by counterexample (analogous reasoning) • How does refutation by counterexample (analogous reasoning) work? – Because validity/invalidity is strictly a matter of argument form, if one can demonstrate that an identical form is invalid (I.e., true premises yielding false conclusion), then the original argument is invalid. • In what way is refutation by counterexample not always reliable? Why do you need to be careful when refuting by analogous reasoning? – You must craft an argument that is exactly identical (logically sensitive) in form--any deviation yields a “false analogy” that will not necessarily disprove the original argument. Chapter 1.3: Categorical Statements • • • • • • • • • • What is a statement? What is a category? What, then, is a categorical statement? Can you cite an example of a categorical statement? What makes it “categorical”? What is the form of a categorical statement? – Can you enumerate the exhaustive list of categorical statement forms? What is a term? – How does it differ from a statement? We will devote chapters 5 & 6 to categorical logic. Commercial break Exercises Chapter 1.4: Induction (Strength & Cogency) • To this point we have limited discussion to issues in deductive logic and only introduced the terms inductive logic (in Chapter 1.1). • How does induction differ from deduction? – What are the standards for deductive logic? – What are the standards for inductive logic? • What three examples of inductive argument types does our text adduce? – How does the idea of “more” or “less” apply to these types? • Exercises Chapters 2.1 & 2.2 (2.3 EC) Preview • WARNING: This chapter may seem “squishy.” – Chapter 2.1—Arguments & Non-arguments • Distinguishes arguments from other kinds of passages, including unsupported assertions, like reports, illustrations, explanations, and conditionals. – Chapter 2.2—Well-Crafted Arguments • Explains how to simplify usually complicated everyday arguments into more assessable well-crafted arguments using six principles to charitably ferret out conclusions, sub-conclusions, explicit and implicit premises, standard form, unnecessary verbiage, and uniformity. – Chapter 2.3—Argument Diagrams (EC) • For extra-credit, demonstrates the helpfully clarifying, but not absolutely essential, step of diagramming arguments schematically in order to grasp the relationship of assertions to their support. Strategic observations • Unlike examples encountered so far in our text, arguments may be extensive and complicated. • There may be arguments supporting premises and premises for those arguments. • There may be more than one line of reasoning for a conclusion. • There may be more than one kind of reasoning. Major tactical maneuvers 1. Begin by asking yourself, “What is the author trying to say? What is his/her point?” This should yield the conclusion. 2. Next, ask yourself, “What are the main reasons she/he adduces for believing that?” This should yield the explicit premises (evidences) of the argument. 3. Finally, ask, “What would one have to believe to accept what this author has said?” This should yield the implicit premises (assumptions) of the argument. Minor tactical considerations • In texts written in English, by writers in Western the tradition, most conclusions appear at the beginning (deductive approach) or at the end (inductive approach) or at the end of the beginning. • Explanations, examples, definitions, and attempts to preempt objections are almost never conclusions of an argument or even premises, in the strict sense. • Ancillary information, as in supporting documentation, notes, parenthetical asides are never conclusions and almost never premises, in the strict sense. • A conclusion will never appear in a subordinate clause. • Look for illatives. Preview of 3.1 - 3.3 • Problem areas – 3.1 • Proposition – 3.2 • Subtlety of definitional terms – 3.3 • Largely unproblematic Why care about definitions? • ‘Define’ literally means to put ‘limits around’ (fr. L. de ‘about’ + finis ‘limit’). • So, definition limits meanings. – Minimizes • vagueness (meanings shading off into other areas) • ambiguity (more than one meaning) – Minimizes complications of “It all depends on what you mean by __________.” Chapter 3.1 • Which of these concepts/terms were difficult? – Proposition – Cognitive meaning – Emotive force • For the concepts/terms that were confusing, can someone clarify it for us by defining and giving at least one example, or the range of examples, of it? • Why is it important to understand these concepts/terms? • Review problematic exercises Chapter 3.2 • Which of these concepts/terms were difficult? – Ambiguity versus vagueness – Extensional definition • Ostensive • Enumerative • Subclassical – Intensional definition • Lexical (genus & differentia) • Stipulative • Precising • Theoretical • For the concepts/terms that were confusing, can someone clarify it for us by defining and giving at least one example, or the range of examples, of it? • Why is it important to understand these concepts/terms? • Review problematic exercises Definition by extension • Pointing (a.k.a. ‘ostensive’) – actually showing one or more cases • Enumeration – listing individual examples • Subclass – listing types or categories • Exhaustive v. non-exhaustive? Intensional definition • Stipulative: personal, ad hoc, coined or not • Lexical: positive, descriptive, dictionary-type, though not necessarily exclusively so • Precising: minimizes vagueness & ambiguity, to “put a fine point on it,” to distinguish precise meaning from popular meaning • Theoretical: places a term in a particular context; may give meaning to both term and context • Persuasive: affective, subjective, emotive Definition by intension • Synonym – Another word (lit. ‘similar’ + ‘name’) • Etymology – Linguistic genealogy (lit. ‘true’ + s ‘account’) • Test – Establishes criteria to be met • Genus + difference/differentia – “garden variety” definition technique: ‘x is a y [that . . . .]’ Chapter 3.2, cont’d. • Which of these concepts/terms were difficult? – Genus versus difference/differentia – Difiniendum versus difiniens – Counterexample • For the concepts/terms that were confusing, can someone clarify it for us by defining and giving at least one example, or the range of examples, of it? • Why is it important to understand these concepts/terms? • What are the criteria for producing a good definition? – – – – – – Not to wide Not to narrow Not obscure, ambiguous, figurative Not circular Not negative if it can be positive Not use unsuitable criteria to determine extension • Review problematic exercises Ways of defining: terms • • • • ‘definiendum’: word to be defined ‘definiens’: words doing the defining ‘extension’: set of objects in defined class ‘intension’: properties of objects in class Rules • What is meant by essential characteristics (necessary & sufficient)? • How can the definiens be too broad or narrow? • What is meant by circularity? • Cite examples of ambiguity, obscurity, figurative or emotive language. Chapter 3.3 • Which of these concepts/terms were difficult? – Equivocation versus merely verbal dispute – Persuasive definition • For the concepts/terms that were confusing, can someone clarify it for us by defining and giving at least one example, or the range of examples, of it? • Why is it important to understand these concepts/terms? • Review problematic exercises Preview of Chapter 4: Concepts that may present difficulty • 4.1 “Fallacies of Irrelevance” – English/Latinate names • 4.2 “Fallacies Involving Ambiguity” – Amphiboly is sort of like equivocation—but it’s not the same. – Composition and division are similar—but they’re not the same. • 4.3 “Fallacies Involving Unwarranted Assumptions” – “Begging the Question” is not what it sounds like. Chapter 4.1: Fallacies of Irrelevance • • • • Which of these concepts/terms were difficult? – Fallacy • Formal • Informal – Of irrelevance » Ad Hominem (Against the Man) » Personal attack » Circumstantial » Tu Quoque » Straw Man » Ad Baculum (Appeal to Force) » Ad Populum (Appeal to the People) » Ad Misercordiam (Appeal to Pity) » Ad Ignorantiam (Appeal to Ignorance) » Ignoratio Elenchi (Red Herring or Missing the Point) For the concepts/terms that were confusing, can someone clarify it for us by defining and giving at least one example, or the range of examples, of it? Why is it important to understand these concepts/terms? Review problematic exercises Chapter 4.2: Fallacies of Ambiguity • Which of these concepts/terms were difficult? – Fallacy of Ambiguity • Equivocation • Amphiboly • Composition • Division • For the concepts/terms that were confusing, can someone clarify it for us by defining and giving at least one example, or the range of examples, of it? • Why is it important to understand these concepts/terms? • Review problematic exercises Chapter 4.3: Fallacies of Unwarranted Assumption • Which of these concepts/terms were difficult? – Unwarranted Assumption • Begging the Question (Petitio Principii) • False Dilemma • Appeal to Unreliable Authority (Ad Verecundiam) • False Cause • Complex Question • For the concepts/terms that were confusing, can someone clarify it for us by defining and giving at least one example, or the range of examples, of it? • Why is it important to understand these concepts/terms? • Review problematic exercises Chapter 5: Categorical Logic Statements • Chapter 5.1 – Terminology is important: we will be coming back to it again and again. – Translation is key: grasp the meaning of stylistic variants and their translation • Chapter 5.2 • Chapter 5.3