Table of Contents - DORAS

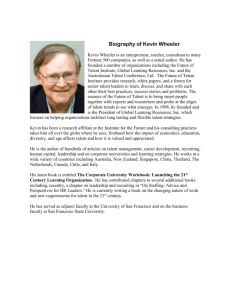

advertisement