Draft Outline for MCGM-NGO Council Public Health Policy Project

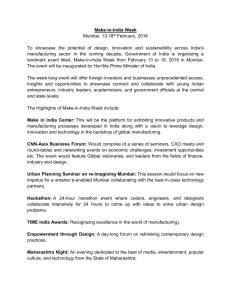

advertisement

Draft Outline for MCGM-NGO Council Public Health Policy Project

Background

This report started as a discussion between the members of the NGO Council and the MCGM

after it was found that there was no existing public health policy document on accessing health

care in Mumbai. The NGO Council is a representing body of NGOs in Mumbai seeking to

collaborate with local authorities on issues of priority. The NGO council was formed on August

22, 2005. The Council is comprised over 70 organizations with complementary expertise

covering all causes and sectors. The primary objectives of the NGO council is to work with

Government, Donors, NGOs, and other third-parties to raise awareness and convene to address

the important issues effecting the city of Mumbai.[1] On 12/12/2005, Municipal Corporation of

Greater Mumbai (MCGM) has entered into an MOU with the NGO Council, recognizing that an

institutionalized partnership between municipal bodies and non-governmental organizations

(NGOs) / civil society organizations (CSOs) is critical for promoting Good City Governance. [2]

Probable Value of the Report

In this section, the author has outlined how the report can be of value to the different existing

bodies in the city of Mumbai. The report was not only created for the MCGM, but also for all the

other proponents of health care in Mumbai. The following section details to value to each

constituency:

MCGM: This report should be seen as an objective analysis of the existing programming at the

MCGM. In addition to giving suggestions, the report also highlights the various successes of the

MCGM’s health programming. It will be of value in several aspects:

Assist lawmakers in allocating funds to priority areas

Provide insight to those responsible for programming in terms of areas of improvement

Increase the efficiency of the MCGM public health department

Increase the reputation of the MCGM’s health services in the city

Prove as an impetus that demonstrates the MCGM’s priority of the health of the people of

Mumbai

Intimate the top-level management as to the priority areas in various departments

Apprise mid-level management of the awareness of the lack of resources

Inform lower-level staff of the value of their work and increase worker morale

NGOs: Non-Governmental Organizations working in Mumbai are working to provide health care

to the same citizens that are also the responsibility of the MCGM. This report can help bring the

two groups together to not replicate programming in high-need areas and pave the way for NGOMCGM partnerships. NGO’s can cite the information in the report as representative of the

enormous need for improved health care systems in such a large and densely populated city.

Donors: With Corporate Social Responsibility representing the progressive era of charitable

giving, it is important for donors to also be aware of the issues that are effecting the communities

that benefit from their time, money, and resources.

Citizens: In a city like Mumbai, the average citizen doesn’t think about health care unless it is a

situation of urgency or crisis. This report will make citizens aware of the issues in health care

that effect all those seeking care through the government health sector.

Medical Students, Physicians, and Health Professionals: In light of the recent strike of the

doctors in Mumbai, it is also important for policy makers to understand the perspectives of those

working on the ground. This report helps shed light on the needs of physicians and avenues for

improvement in their occupation.

Media: The MCGM health department is often the recipient of negative publicity by the medial.

The information in the report can offer some information as to the inner workings of the MCGM

health department and what the media can do to support the improvement of these systems.

Overall, the report provides an in-depth analysis of the existing programs, challenges, and

successes of the MCGM health department. Looking at the history of health policy in India, it is

evident that there has been little emphasis on improving the health of local citizens in recent

years. The report attempts to create a common area for discussion and improvement of health

systems within this city. With good basic infrastructure, there are many avenues that can be

pursued if the aforementioned parties join together to work on a healthy Mumbai.

Conclusions and Summary

In the last 20 years, there have been few initiatives proposed to improve health for the citizens of

India. When looking at the policies and initiatives proposed by the Central Government, there is

a clear emphasis on improving rural health. However, with the urban poor population rising, the

health needs of the urban poor communities are beginning to exceed those in the rural

communities. The health care crisis of the growing urban poor, especially in Mumbai, represents

a new challenge in providing health care to the masses. The health care of the urban poor is often

worse than or equal to that of the rural poor population. Over 50% of Mumbai’s population of 18

million[3] lives in slums and are part of the growing urban poor. This population is plagued with

uneven access to care, malnutrition, and poor maternal and child health. Therefore, it is critical to

look at the health of Mumbai on a continuum of urban health.

The MCGM (Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai) provides medical services through

three levels of care, primary, secondary and tertiary. This includes an intricate network of

teaching hospitals, secondary hospitals, maternity homes, health posts and dispensaries.

Although the infrastructure is complex, there is a multitude of improvements needed to address

the health needs of the urban poor population in Mumbai. The various challenges plaguing the

MCGM health system are growing as rapidly as the population and need to be addressed

urgently. The challenges include:

Human Resources: A large amount of vacancies in the public health department of the MCGM

lead to the apathy of the staff and patients.

Infrastructural: Lack of equipment and services at the primary and secondary level of care; lack

of referral systems to direct patients to the appropriate care level; lack of quality assurance

Systems: Lack of a centralized data system, lack of awareness of existing programs within the

MCGM

Ethical: Dilution of the value and faith in the public health system as a facility for all, not just the

indigent and underprivileged. This is a phenomenon that affects the patients as well as the staff.

Educational: Educational materials for prevention of disease and promotion of health are underutlilized or unavailable, patients do not understand the complexities of their own health

With a confident team, collaborations, and an open attitude toward change, there are many

options for the MCGM health system to become an accessible service for people seeking quality

health care at an affordable price. A no-frills health care system that emphasizes good quality at

the lowest possible cost to the consumer will not only benefit the poor, but also those taxpayers

whose money is being invested in the government run health care system. Working with existing

private providers and NGOs can be beneficial for the MCGM system in terms of decreasing the

burden and using best practices of existing programs.

Utilizing best practices from cities with similar problems to Mumbai will provide some insight

into innovations that could be implemented throughout the existing health systems. While the

problems sometimes seem to vast to deal with, it is important to remember that an

implementation strategy that works on a step-by-step approach will be the ideal method of

slowly improving the system. The MOU between the NGO Council and the MCGM is the

critical agreement that should be kept in mind in the difficult stages of planning and

implementation. This agreement is meant to bridge the gap between the government and the non

profit organizations that provide many needed services to the impoverished. Both have similar

goals, it is now time to devise a better strategy through collaboration.

Recommendations- Brief

A. Education and Information Dissemination

Ensure that a Patient Bill of Rights (enclosed) and Patient Code of Conduct are posted in every

public health care facility being operated by the MCGM

Create a map of Mumbai (in Hindi, Marathi, English, etc) with locations, timings, and services of

each healthy care facility.

Improve primary and secondary health care systems by providing training for quality assurance

at all facilities.

E

nsure that educational materials on ALL illnesses and ailments are available in multiple

languages at respective primary and secondary health care levels via posters, pamphlets, and

CHVs.

B. Reproductive and Child Health

Increase awareness about institutional deliveries by collaborating with local women’s groups.

Develop IEC materials relevant to reproductive and child health as well as other relevant

diseases by working with NGOs

Ensure all maternal, reproductive and child health services are free of cost.

Ensure that all municipal facilities are always stocked with medications for pre-natal care (iron,

folic acid etc.)

C. Medical and Administrative Personnel

Increase skills, salaries, and working hours of the Community Health Volunteers and have

CHV’s collaborate with health workers from NGOs

Discontinue the practice of allowing doctors to have private practices while employed by the

MCGM.

De-centralize the management of the primary and secondary health care services

D. Infrastructure

Hire staff to fill vacancies of doctors at the primary health care level (Health Posts and

Dispensaries) to improve the quality of care

Conduct a needs assessment of the infrastructural (both equipment, human resources) gaps in the

MCGM public health system via a survey and analysis to apply appropriate solutions.

Decrease the gaps in infrastructure (staff, equipment, and training) at the primary and secondary

levels of health care

Create a referral system so that people can access the medical services at the appropriate lowest

level.

Utilize the referral system to minimize costs, patient load, and provide better quality treatment

for serious cases.

Create management information systems to store and utilize data, statistics, and health records

appropriately.

Create systems for MCGM circulars to be accessible to all

Revamp the ambulatory system completely to provide emergency care as well as transport.

De-centralize the laboratory system. Ensure all peripheral hospitals have functional labs.

E. Systems

Create a patient feedback system to improve policies, procedures, and services for patients and

for MCGM staff.

Create a Public Health Monitoring Department that meets once in 2 months to plan for upcoming

public health issues (i.e. bird flu, leptospirosis).

F. Coordinating with other MGCM Departments

Introduce adolescent health education through the municipal school system.

Increase citizen participation through a public health citizen committee in collaboration with the

MCGM public health department.

Improve disaster management to minimize public health outbreaks

Improve water supply and sanitation at all slums, this will decrease the amount of diseases in the

area.

G. Priorities in Health

Create a department that addresses issues of respiratory health in Mumbai, this should also be a

division of the school health department

Utilizing the existing DOTS program, increase the priorities of TB management

Implement more programs focused on decreasing IMR and MMR (these should be focused on

nutrition, education, and health of the mother as well as the child)

Create a city-wide campaign regarding Malaria awareness to be promoted during and before

Malaria months

Ensure that all vitamins and supplements are available to NGOs distributing them to children

through various programs

Patient Bill of Rights

Each place posting the Patient Bill of Rights needs to affirm the following statement.

"We, the staff and the administration of {health facility} declare the following Bills of Rights

for the patients of this medical facility. As per the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai, we

declare that staff and administration of {the health facility} have read and understood the

following rights of a patient and hereby agree to all the terms listed below. If you have any

questions or complaints, please contact {Name of accountable person at health facility} or {name

of accountable person at BMC}."

To be treated with dignity irrespective of their caste, class, sex, religion, and disease

To have a list of exact services available and corresponding fees (for supplies, bandages, etc)

To have a visible map of the hospital (in Marathi, Hindi, English, and other languages)

To have a list of emergency services such as blood banks and ambulatory services listed in

Marathi, Hindi, English and other languages

To know and understand the procedures involved

To be given a reasonable time frame for the treatment and receive a proportional discount in fees

for all services after the upper limit of approximation is over and treatment needs to be continued

To have a comprehensive (various tests, blood work, x-rays, room tarrifs, operations, consulting

fees, etc) costs associated with seeking medical care

To receive prompt and courteous care

To be informed about the documentation needed for treatment

To have minimal documentation for emergency cases

To receive Reproductive and Child Health Services free of cost at public health facilities

To receive medications and vaccinations from the local public health post or dispensary

To get medical services which are within the capability of the medical facility

To obtain from the doctor complete information concerning the diagnosis, treatment, and

prognosis in language the patient can understand.

To receive necessary information from the doctor such as long-term effects, side effects etc.,

before giving any prior consent to a medical procedure and/or treatment

To receive the records or a certified copy that gives the details of the disease, treatment, and

follow-up necessary at the time of discharge

To refuse the suggested treatment and be informed of the medical consequences thereof

To receive medical care in well-equipped and sanitized conditions

To receive quality care from competent medical professionals

To select doctor’s of one’s choice when possible

To obtain a second opinion

To privacy during medical check-ups

To be assured that all communication and records will be kept confidential

To educational information about medical problems eg. via a library, IEC materials, etc.

To receive a bill cum receipt after the payment is made

To be enabled to pay hospital fees on a payment plan

To have access to a non-hospital staff member appointed to address complaints as soon as

possible

To have the contact information of the responsible person (both at the hospital and head office)

to register a complaint or give feedback

To have adequate waiting space

To allow relatives to have flexible visiting hours

Patient Code of Conduct

Patients are also responsible for their personal and environmental well-being. The following

code of conduct emphasizes the responsibilities of a patient while seeking medical care.

As a patient:

You should provide the doctor with accurate and complete information about his/her medical

history, past illnesses, allergies, hospitalizations, and medications

You should report the changes in your medical changes

You should ask for clarity if the doctor’s prescription and diagnosis seem unclear

You should follow the doctor’s treatment plan

You should pay your medical bills promptly

You should follow hospital rules and regulations

You should have realistic expectations of what the doctor can do for you

You should help your doctor help you, if something isn’t working, be clear and the doctor can

advise alternative care

You should participate actively in your own medical care (in terms of awareness and

preventions)

You should ask the doctor questions to clarify any doubts or misconceptions in your mind

You should treat the doctors with respect

You should not ask doctors for false bills or certificates for any reason

I. Recommendations- Expanded

A. Education and Information Dissemination

Ensure that the Patient Bill of Rights and Code of Conduct (attached) is posted in every public

health care facility being operated by the MCGM

Action Steps:

Translate the documents into Hindi, Marathi, and other regional languages

Pilot test it with a core group to ensure comprehension of the concept and what it actually would

mean

Send around a circular for ALL staff to read and understand the Bill of Rights and Code of

Conduct

Post accordingly in all health care facilities in Mumbai

Time line: 2 months

Measure of Success: Increased awareness of rights and responsibilities of patients, perhaps

greater accountability of staff

Create a map of Mumbai (in Hindi, Marathi, English, etc) with locations, timings, and services of

each healthy care facility.

Action Steps:

Hire a group of college students for 2 months to work with the Public Health Department to

come up with a map that identifies all the locations of the health facilities

This should include timings, doctor’s name, and phone number

This map should be updated twice a year by the Public Health Department, once the

infrastructure is in place

Time line: 2 months

Measure of Success: Increased awareness of government facilities, accountability for doctors,

less patient load at tertiary care services

Improve primary and secondary health care systems by providing training for quality assurance

at all facilities.

Before implementing any kind of quality measures, the entire MCGM public health department

(from the sweeper to the doctor) should understand the need for such innovations

Through role plays and consciousness raising, the staff should become aware of the challenges

before them

Hold monthly meetings with staff to imbibe aspects of quality assurance throughout the MCGM

public health department

Utilizing the health committee formulated, hold trainings for improved quality of care

Provide incentives for randomly conducted surveys of facilities that provide quality care to their

patients

Time line: 4 months

Measure of Success: Increased patient satisfaction as well as improved attitudes among staff.

Ensure that educational materials on ALL illnesses and ailments are available in multiple

languages at respective primary and secondary health care levels via posters, pamphlets, and

CHVs.

Action Steps:

Collaborate with the HELP library to create educational materials

Make sure such materials are available at ALL health facilities being run by the government

sector

Ensure that a wide array of languages are covered in these materials

Time line: 3 months

Measure of Success: Increased patient health education, awareness of preventable diseases

B. Reproductive and Child Health

Increase awareness about institutional deliveries by collaborating with local women’s groups.

Action Steps:

Engage NGOs to help involve Mahila Mandals

Create awareness among leaders in these groups about the hazards of home deliveries

Hold events and public gatherings to raise awareness among these women’s groups

Time line: Ongoing, but start up should be 3 months

Measure of Success: Increase in amount of institutional deliveries at the hospitals in the areas

where the education has taken place.

Develop IEC materials relevant to reproductive and child health as well as other relevant

diseases by working with NGOs

Action Steps:

Team up with 5 NGO Partners in order to start collecting information that already exists on these

topics

Devise a strategy to review these materials and edit/modify as needed

Print and distribute to all women

Time line: Ongoing, but start up will be 2 months

Measure of Success: Increased awareness of RCH as well as other diseases; may lead to

prevention

Ensure all maternal, reproductive and child health services are free of cost.

Action Steps:

Appeal to the budget making entities of the value of free RCH services

Create a public service campaign regarding increasing awareness for these initiatives

Time line: Ongoing campaign, start up will be 2 months

Measure of Success: More urban poor women accessing government health care facilities for

prenatal, postnatal, and neonatal care

Ensure that all municipal facilities are always stocked with medications for pre-natal care (iron,

folic acid etc.)

Action Steps:

a. Partnerships with pharmaceutical companies can guarantee a constant stock of these very

necessary vitamins and supplements

b. An education campaign should educate women of the value of the proper utilization of these

medications before and during pregnancy

Time line: 2 months

Measure of Success: Decreased infant mortality and maternal mortality rates

C. Medical and Administrative Personnel

Increase skills, salaries, and working hours of the Community Health Volunteers and have

CHV’s collaborate with health workers from NGOs

Action Steps:

Expand job descriptions to include more responsibilities of the CHVs

Increase salary to Rs. 1000 per month

Provide ongoing trainings for them to be more engaged in the work they do

Allow them to collaborate with local NGOs CHW’s as well

Time line: 4-6 months

Measure of Success: Increased job satisfaction and output by the CHVs, greater collaboration

and raising awareness

Discontinue the practice of allowing doctors to have private practices while employed by the

MCGM.

Action Steps:

As an overall initiative, doctors should shut down their private practices at MCGM facilities

Terminate all benefits for those that had such practices

Time line: 1 month

Measure of Success: Discontinuation of private practices for MCGM doctors

De-centralize the management of the primary and secondary health care services

Action Steps:

Allow Medical Officers in each ward to take the lead in decision making

Tell them they have a certain amount of money in the budget and set realistic goals

Encourage them to reach these goals through collaboration and hard work

If they demonstrate leadership skills, there can be incentives for group management of wards

(rather than it always having to be cleared through the main office)

Time line: 4 months

Measure of Success: Increased job satisfaction and participation in the process

D. Infrastructure

Hire staff to fill vacancies of doctors at the primary health care level (Health Posts and

Dispensaries) to improve the quality of care

Action Steps:

a. Revise the personnel policies for the doctors at the primary health care to improve salaries and

make sure the following basic facilities are available at every dispensary:

Equipment to sterilize the instruments used for examination

Ample medications for all basic illnesses (diarrhea, cough, cold, flu, and fever)

Enough stock of iron, folic acid, for supplying to all women who may come to register their

pregnancies

Training in the basics of pre-natal care for community health volunteers

X-ray facilities at certain upgraded facilities

b. Collaborate with medical schools to create incentives for graduating students to commit 2

years to service at the primary or secondary level

c. Involve current doctors in recruiting of new physicians, offer incentives to those who can find

doctors who sign contracts for 2 years or more.

d. Improve the overall image of working for the MCGM improving facilities and systems

through a circular highlighting the successes of the primary health care physicians

Time line: 6 months

Measure of Success: Decreased vacancies, greater staff job satisfaction

Conduct a needs assessment of the infrastructural (both equipment, human resources) gaps in the

MCGM public health system via a survey and analysis to apply appropriate solutions.

Action Steps:

Create a simple survey to assess the equipment, amount of staff, medicines etc.

Utilizing the CHV’s (increase their work hours and pay to Rs.1000) to have a basic assessment

of equipment, vaccinations, medicines, vitamins etc (each CHV would assess a health post

different from their own to maintain objectivity

Put all the data gathered together in a simple report revealing the gaps in services and

infrastructure at the primary level

Time line: 3 months

Measure of Success: A report that identifies the gaps and direct action by the administration.

Decrease the gaps in infrastructure (staff, equipment, and training) at the primary and secondary

levels of health care

Action Steps:

Utilizing the assessment in Recommendation 13, assess the needs of each of the primary and

secondary health care facilities.

The health committee can further lobby the administration about improving the infrastructure at

each of these locations.

Infrastructure specifies: lab equipment, x-ray facilities, storage for vaccinations, provisions for

sterilizing needles, and other needs identified by the survey.

Time line: 6 months

Measure of Success: Increase in utilization at the primary and secondary levels of health care,

increased resources and infrastructure.

Create a referral system so that people can access the medical services at the appropriate lowest

level.

Action Steps:

In 5 wards, pilot test the referral system of care described in the Appendix 1, already tried once

by the Women Centered Health Project.

Using the lessons learned by SNEHA’s CINH program that brings together NGOs and public

health systems, implement 3 wards using their methods.

Assess the pilots and determine which was most complementary to the needs of the patients that

access the MCGM health care system.

Time line: 1 year

Measure of Success: No overcrowding at tertiary hospitals, greater patient understanding of

each of the tiers and what they offer.

Create management information systems to store and utilize data, statistics, and health records

appropriately.

This can be a part of the TCS created system.

Create systems for MCGM circulars to be accessible to all

Action Steps:

Using a computerized system, circulars should be sent out to all departments, and not just

specific departments

The circulars should be stored in a computer as well as hard copy

TCS is also implementing a computerized network, this should be a part of it.

Time line: 6 months

Measure of Success: Improved record-keeping and awareness of all the programs/updates going

through the MCGM system.

Revamp the ambulatory system completely to provide emergency care as well as transport.

Action Steps:

Create a public-private company willing to partner with the MCGM on issues of ambulatory care

Create minimum qualification guidelines of those operating the vehicles

Ensure the vehicles are well equipped with supplies and equipment for saving lives

Create a free call system for people to call this number 24 hours a day

Cost? Should be further discussed

Time line: 6 months

Measure of Success: Decreased deaths due to the scarcity of quality ambulatory care, perhaps

some benefits from the public-private partnership

De-centralize the laboratory system. Ensure all peripheral hospitals have functional labs.

Action Steps:

Using the infrastructure survey, it is important to assess which areas are lacking proper labs

These labs should be equipped to test for TB, AIDS, and conduct all other necessary blood work

on site

There should be no additional user fees associated with this service

Time line: 4-6 months

Measure of Success: Decreased load on the 3rd tier lab systems, better facilities for patients to

access blood work results

E. Systems

Create a patient feedback system to improve policies, procedures, and services for patients and

for MCGM staff.

Action Steps:

Through a screening process, select non-hospital staff to field the concerns of patients

Ensure the person is competent in mediation and can handle high pressure situations

The person will then bring the issue to the hospital administration team to be addressed within a

certain time frame depending on the emergency

Ensure this process is well documented with appropriate attention from administration for

complaint management

Time line: Ongoing, set up time 3 months

Measure of Success: Decreased frustration among patients and staff alike, decreased attacks on

doctors

Create a Public Health Monitoring Committee that meets once in 2 months to plan for upcoming

public health issues (i.e. bird flu, leptospirosis) and acts a citizen body to represent the concerns

of the locals.

Action Steps:

Review examples of Porto Alegre and other participatory/citizen committees

MCGM’s public health department should set up an open house day to invite all interested

parties to learn more about how the MCGM works.

The main role of the committee should be monitoring upcoming health issues and creating a

forum for discussion and preparedness (i.e. avian flu, monsoon related illnesses)

Utilize media partners to help support and promote the outputs of this collaboration

Time line: 6 months

Measure of Success: Increased citizen participation and actual change as a result of the

participation.

F. Coordinating with other MGCM Departments

Introduce adolescent health education through the municipal school system.

Action Steps:

Work with the Niramaya Health Foundation which just launched SPARSH, an adolescent health

education initiative

Pilot this initiative at some of the schools

Replicate and disseminate

Time line: 6 months

Measure of Success: Increased awareness in adolescent health, increased awareness among

children on life skills and personal health

Improve disaster management to minimize public health outbreaks

Action Steps:

Work closely with the disaster management cell and the NGO Council to start to address some of

the issues related to disaster management

Educate the city through the LACGs on the importance of preparedness

Ensure the release of it before onset of monsoon season

Time line: 4 months

Measure of Success: Increased confidence in the public health system, increased preparedness

for individuals and families

Improve water supply and sanitation at all slums to decrease the amount of diseases in the area.

To be further developed.

G. Priorities in Health

Create a department that addresses issues of respiratory health in Mumbai, this should also be a

division of the school health department

Action Steps:

Conduct an in-depth analysis of the respiratory health of Mumbai

Work with NGOs to create greater awareness

Create a cell within the school department so children can be screened for respiratory issues

Further follow up will be needed by the public health and the school department

Time line: 6 months

Measure of Success: Increased awareness of respiratory health, greater initiatives to address

them

Utilizing the existing DOTS program, increase the priorities of TB management

Action Steps:

Given the numbers of cases and deaths reported in the Mumbai health profile, it is critical that

there be more initiatives to address TB in Mumbai

Create a commission to address why there are still so many cases despite the presence of DOTs

Ensure that people suffering from TB are not building up a resistance to the medication.

If that is the case, there needs to be further concentration of a public health strategy in this area

Time line: 1 year

Measure of Success: Decreased deaths and cases reported due to TB in Mumbai

Implement more programs focused on decreasing IMR and MMR (these should be focused on

nutrition, education, and health of the mother as well as the child)

Action Steps:

Work with NGOs like SNEHA and CCDT to look at how they are improving systems to support

better Reproductive and Child Health

Utilize the benefits of the new RCH II policy that was released as an impetus for improving the

health services provided to women and children

Time line: 6 months, ongoing

Measure of Success: Decreased IMR and MMR (at least by 30-40%)

Create a city-wide campaign regarding Malaria awareness to be promoted during and before

Malaria months

Action Steps:

Given the fact that Malaria is a major problem in climates like those of Mumbai, it is critical that

the Public Health Department address this issue

Teach the public about increasing awareness about the dangers of malaria and how to prevent it

Provide citizens with information through the LACG meetings

Information should be circulated in all newspapers

NGOs and the MCGM can collaborate on this campaign

Time line: Ongoing

Measure of Success: Decreased cases and deaths by Malaria

Ensure that all vitamins and supplements are available to NGOs distributing them to children

through various programs

Action Steps:

Every month the MCGM should conduct an inventory of the stock

NGOs should submit requests for vitamins 2 months in advance

Stock should always be ensured and monitored

Time line: 3 months

Measure of Success: Increased availability of critical nutrients necessary for the development of

children

II. Executive Summary

Introduction

This report started as a discussion between the members of the NGO Council and the MCGM

after it was found that there was no existing public health policy document on accessing health

care in Mumbai. The NGO Council is a representing body of NGOs in Mumbai seeking to

collaborate with local authorities on issues of priority. The NGO council was formed on August

22, 2005. The Council is comprised over 70 organizations with complementary expertise

covering all causes and sectors. The primary objectives of the NGO council is to work with

Government, Donors, NGOs, and other third-parties to raise awareness and convene to address

the important issues effecting the city of Mumbai.[4] On 12/12/2005, Municipal Corporation of

Greater Mumbai (MCGM) has entered into an MOU with the NGO Council, recognizing that an

institutionalized partnership between municipal bodies and non-governmental organizations

(NGOs) / civil society organizations (CSOs) is critical for promoting Good City Governance. [5]

The relationship between the NGO Council and MCGM has been utilized in various Solid Waste

& Local Area Citizen Group initiatives. This report was initiated to maximize the output of the

public health system. This report is an in-depth policy analysis into Central and Municipal

policies pertaining to health via an analysis of existing programs, successes, challenges, personal

interviews, conclusions, and recommendations. The purpose of the report is to highlight what is

working and offer suggestions for where improvements can be made. This report serves as an

initial policy document necessary to begin conversations on trends in public health in Mumbai.

As India becomes a major player in the global economy, it is critical that local governments

understand the global repercussions of a weak health system in light of a strong economy. Since

Mumbai already has an existing infrastructure to catalyze these efforts, it is in this spirit that we

propose that the MCGM and NGO Council work together to address the issues in health in

Mumbai.

2. National Policies in Health Care in India National Health Policy 1982

The first national health care policy was written in 1982 by the Central Government. This policy

was created to set a primary objective of Health Care for All by 2000. The establishment of

efficient and effective primary health care systems, especially for the vulnerable: the

underprivileged, women, and children were critical elements of achieving health care for all by

2000. The GOI had set an ambitious agenda for improvement of health of the Indian citizen. An

integrated network of evenly spread specialty and super-specialty services was specified in the

draft. Since implementation of NHP-1983, the national health program was able to achieve some

successes in health care. Smallpox and Guinea Worm Disease have been eradicated from the

country; Polio is on the verge of being eradicated; Leprosy, Kala Azar, and Filariasis can be

expected to be eliminated in the foreseeable future. There has been substantial drop in the Total

Fertility Rate and Infant Mortality Rate. The life expectancy has gone from 36.7 to 64.6 in 50

years. The Infant Mortality Rate (IMR) has been cut in half since 1951.

Fifty years later, the achievements of this policy only represent a fraction of the need that exists

in India. Ironically, with a hike in user charges, proposals of privatization of government

hospitals, and increasing healthcare costs, the year 2000 represented a dynamic turn in the

intended goals of NHP-1983.[6]The burden of cost of care subsequently has shifted from being

the responsibility of the government to becoming a burden on the patient seeking care. A

retrospective analysis of the NHP-1983 alludes to the fact that the policy may have been over

ambitious considering the infrastructure that existed at that time.

National Health Policy 2002

The next National Health Policy was written in 2002, when public health investment was at an

all time low, 1.3% of the GDP in 1990 to .9% of the GDP in 1999 (GOI, 2002). The aggregate

expenditure in the Health sector is 5.2 percent of the GDP. Out of this, about 17 percent of the

aggregate expenditure is public health spending, the balance being what ends up being out-ofpocket expenses.[7] The central budgetary allocation for health over this period, as a percentage

of the total Central Budget, has been stagnant at 1.3 percent, while that in the States has declined

from 7.0 percent to 5.5 percent.

NHP 2002 expounds that country wide, less than 20% of the population which seeks OPD

services, and less than 45% of those that seek indoor treatment, avail services such as public

hospitals. This low incidence of seeking OPD (Out-Patient Dispensary) treatment is due to

unsatisfactory factors like time, workday loss, lack of faith in medication as also the outside

medical prescriptions The NHP 2002 firstly stresses the aspect of vertical programming in

current public health services provided by the government; keeping in mind that horizontal

programming (health programming that works within several sectors to accomplish similar

goals) would be more cost effective for the kind of health needs of the population on India.

Secondly, there is an imperative need to upgrade the national and statewide Disease Surveillance

Network.

Overall, the NHP-2002 document envisions the existence of an organized primary health care

structure. Since the physical features and needs of urban settings are different from rural areas,

there is a need to set a different set of measurable criteria for urban health care. In addition to

improved ambulatory and emergency care, in urban settings, the NHP-2002 emphasizes a 2

tiered healthcare system:

Primary Health Care: 1st Tier; serve a population of 1 lakh, dispensary for OPD and essential

medications

Secondary Health Care: 2nd Tier; a government hospital, where a referral is made from the

primary health centre[8]

Although the NHP-2002 document is quite thorough, it covers just basic objectives in urban

health care for the poor, which are the upcoming communities that will need the attention of the

government. The aforementioned objectives are part of the mandate for improved services in

public health services in an urban setting.

National Population Policy

The National Population Policy (NPP), drafted in 2000, also includes the critical aspect of urban

health care and its effect on population policy. The NPP 2000 affirms the commitment of

government towards voluntary and informed choice and consent of citizens while utilizing

reproductive health care services, and continuation of the target free approach in administering

family planning services.[9]

The NPP 2000 provides a policy framework for advancing goals and prioritizing strategies

during the next decade, to meet the reproductive and child health needs of the people of India,

and to achieve net replacement levels (or Total Fertility Rates) by 2010. It is based upon the need

to simultaneously address issues of child survival, maternal health, and contraception, while

increasing outreach and coverage of a comprehensive package of reproductive and child heath

services by government, industry and the voluntary non-government sector, by working in

partnership.[10] The NPP document emphasizes the importance of connecting population policy

to health care systems “it is as much a function of making reproductive health care accessible

and affordable for all, as of increasing the provision and outreach of primary and secondary

education, extending basic amenities including sanitation, safe drinking water and housing,

besides empowering women and enhancing their employment opportunities, and providing

transport and communications.[11]

Report of National Commission on Macroeconomics and Health

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, a division of the Government of India, submitted

this report in 2005 with the intention of taking an informative look at the health of the nation.

The terms of reference of the National Commission on Macroeconomics & Health (NCMH),

included among others, a critical appraisal of the present health system — both in the public and

the private sector — and suggesting ways and means of further strengthening it with the specific

objective of improving access to a minimum set of essential health interventions to all. It was

also intended that the Commission would look into the issue of improving the efficiency of the

delivery system and encouraging public-private partnerships in providing comprehensive health

care.[12]According to the NCMH report, the public health system in India is currently

overwhelmed by the co-existence of communicable and infectious diseases, alongside an

epidemic of non-communicable diseases (Cardiovascular diseases, cancer, diabetes, etc). Even

with existing interventions, communicable diseases are expected to decline, but there are further

risks with the emergence of new infections and non-communicable diseases that will need to be

addressed as well.

As the report is focuses on the macro-economic perspective of health, the NCMH postulates the

three major drivers of health care costs as[13]:

Human Infrastructure: Cost of staffing the health needs of the country

Drug Regime: Cost of drugs is an issue

Technology Used: Advancing health care to suit the countries needs through the use of

technology

World Health Organization Country Profile

The World Health Organization Country Profile gives an overview of the health of the country.

The World Health Organization has also analyzed the health of India. According to a report on

India by the World Health Organization (WHO) there are approximately 501,900 doctors in the

country, which equals 5.2 docs per 10,000. This is important as these doctors not only look after

a large population in urban pockets and many are even employed by many private hospitals. The

number of nurses/midwives are about 607, 376.[14] Other problems in health resources include a

shortage of funds and government medical training and there are many vacancies in lab techs,

radiologists, for diseases like malaria and tuberculosis.

Overall, the health policies of India seem to overlap in areas such as access to health, nutritional

deficiencies, lack of resources, high rates of infant and maternal mortality, lack of primary health

care services, lack of expenditure as per the state governments, and the presence of

communicable, non-communicable, and infectious diseases all at the same time. However,

through the NHP-2002, NPP-2002, the NCMH report, and the country health profile of the WHO

collaboratively offer various solutions to the aforementioned challenges in country-wide health

care. While it is clear that there have been initiatives to address health in India, it has primarily

been from a rural perspective. A closer look at the changing population intimates us that the

urban poor are the ones suffering from a new illness: access to health care.

3. Urban Poor and Health

Although the focus of many of the Central government initiatives for health have been focused

on the rural sector, it is critical to now start exploring the gaps in urban health care. Rapid and

unplanned urbanization is a marked feature of Indian demography during the last 40-50 years.

According to the 2001 census, India’s urban population currently accounts for almost 30% of the

population (approximately 285 million). This represents a 100 times increase in the past century

and nearly 40% increase during the last decade. The population and the amount of urban poor are

rapidly increasing and contributing to a significant strain on resources. The unabated growth of

the urban poor is leading to what is currently being called the “2-3-4-5 Phenomenon of

Population Growth”, which states that the Urban Population is India is currently at 285

million[15], urban poor are estimated at 70[16]-90[17] million, and the estimated annual births

among the urban poor are 2 million.[18]

The health conditions of the urban poor are similar to or worse than the rural population and far

worse than urban averages. High infant and maternal mortality, malnutrition, lack of access to

services, sub-optimal health behaviors, and inadequate public sector reproductive and child

health services. The Environmental Health Project (EHP), a project of USAID has re-analyzed

the (NFHS) National Family Health Survey (1998-1999) in 2003 and found that the health of the

urban poor has been under-estimated up to this point. The tables below have been adapted from

the EHP website. A closer comparison between the problems of the rural population versus the

urban poor gives greater insight into the upcoming challenges in urban health. As the country

shifts to the urban areas, evidence demonstrates the need for more of a focus on improving

(access to) urban health care.

Urban health care in Mumbai

In Mumbai, a city of approximately 18[19] million people, over 50% of the population lives in the

slums. With a city’s population expanding at a rate faster than infrastructure to address it, health

is likely to be impacted severely, with the underprivileged communities being the hardest hit. In

Mumbai, urban poverty manifests into informal settlements and slums which have little or no

access to sanitation, water supply, education, and health infrastructure. This dramatic increase in

the population of cities in developing countries has put enormous pressure on services like water,

sewerage, housing and transport.

The infant mortality rate (IMR) in the city is 40% and the maternal mortality rate (MMR) is

14%. The survey conducted by Reproductive and Child Health (RCH) and Centre for Operations

Research and Training (CORT) in 1999 states the sex ratio in the city as 872 females per 1000

males, net migration has contributed 19% to the population growth of the city. The crude birth

rate (CBR) in the city is 16.6 per 1000 and the general marital fertility rate (GMFR) is 108.7 per

1000. Nearly 76% of the children and 42.1% of women in the city are anemic; this percentage in

the slum and non-slum areas is 45.5 and 37.4, respectively. Nearly 50% of the children under

three years are underweight (measured in terms of weight-for-age), 40% are stunted (height-forage) and 21% are wasted (weight-for-age).[20]

According to the Maharashtra Economic Survey 2004-05, the incidence of poverty in the rural

areas of the State dropped from 58% per cent in 1973-74 to 24% per cent in 1999-2000. In the

same period, in urban areas it dropped from 43.9 per cent to 26.8 per cent. At present, the

incidence of poverty is higher in urban areas than in the rural areas.

Of the 2,38,247 children weighed in June 2005 at various anganwadis in Mumbai, 1,066 were

severely malnourished, according to government figures. In 2002, a study conducted by Neeraj

Hatekar and Sanjay Rode of the University of Mumbai's Department of Economics, projected a

floor estimate of least about 750 children dying of malnutrition in Mumbai alone each

year. [21] Further, the rates of malnutrition are higher in the urban poor than the rural average.

When looking at access to health services, the presence of infrastructure seems to make little

difference in how the poor seek health care. Table 3.1 indicates that despite the presence of

infrastructure (hospitals, health posts), only about 43% of the urban poor actually access health

services.

Mumbai is a good example of challenges of health care access for the urban poor. With some of

the finest health care institutions in the country, the urban poor often face health problems that

are similar to those effecting the rural population. The next section provides insight into the

existing health infrastructure in the city of Mumbai.

Existing Infrastructure in Mumbai

The MCGM’s existing public health system is a stark contrast in infrastructure and utilization.

Under its programs for public health care, the MCGM runs four major hospitals, 16 peripheral

hospitals, five specialized hospitals, 168 dispensaries, 176 health posts, and 28 maternity homes

with a staff of over 17,000 employees. The Corporation also runs three medical colleges. Of the

total 40,000+ hospital beds in the city, the MCGM run hospitals have about 11,900 beds. As

many as 10 million patients are treated annually in the Out-Patient Departments (OPDs) in the

MCGM hospitals.

The largest hospital, the King Edward Memorial Hospital and Medical College, alone annually

treats 1.2 million patients in its OPD. The state government has one medical college, three

general hospitals and two health units with a total of 2,871 beds. Each of the peripheral hospitals

is linked to one of the four super specialty hospitals. The health posts and the dispensaries are

linked to the peripheral hospitals in their respective Wards. These health posts were established

under the World Bank Funded project called IPP-V, and resulted in the set up of the Health Posts

which were meant to serve as the primary link between the citizen and the government.[22]

MCGM Facilities and Programs

In addition to the hospitals run by the MCGM there are secondary hospitals, maternity homes,

health posts, and dispensaries that are under their jurisdiction. There are 168 dispensaries and

176 health posts set up in Mumbai. The health posts were set up from a World Bank Initiative

called IPP-5 (India Population Project 5) which sought to set up primary health care centers in

Mumbai from 1988-1996.

The health posts provide medications for DOTS as well as medications for basic ailments

(cough, cold, fever, gastrointestinal issues) while the dispensary has a doctor that is there to

provide medical check ups. These dispensaries and health posts often don’t function at maximum

utilization rates due to large scale vacancies, disconnect of the staff and the community, and

general ignorance toward quality. While there are always exceptions, due to the overall lack of

facilities and resources given at the primary level, health posts are not universally utilized to

access primary health care.

There are 28 maternity homes run by the MCGM. Maternity homes were meant to be a referral

point from the primary health care systems. In an ideal situation, if a pregnant woman went to a

dispensary for prenatal care, a doctor there would refer her to a maternity home or peripheral

hospital for institutional delivery. However, the maternity homes are suffering under severe

neglect due to lack of equipment, on the site decision making, and quality of care. Additionally,

the controversial practice of charging fees for reproductive and child health has led to an

apathetic view of maternity homes.

Municipal hospitals are meant to be the secondary and tertiary points of care for the patient

seeking healthcare in Mumbai. These hospitals also should be used as referral points, but when

patients have a free range of choices, as is in the MCGM health system, most of the primary

infrastructure is bypassed. There are four major hospitals, 16 peripheral hospitals and five

specialized hospitals. The four major hospitals are also medical colleges which infuse them with

a greater amount of financial resources and recognition than in the peripheral hospitals. The

peripheral hospitals should be a secondary referral point from the primary health care centers;

however, it is also plagued with low resources, centralized decision making, and little attention

on quality of care. If an urgent case is brought to a secondary hospital, it tends to be transferred

to a major hospital, and due to problems in ambulatory care, patients have little chance of

survival.

The various programs include:

Leprosy Program: An initiative to address and contain Leprosy in Mumbai

Tuberculosis Program: To address, treat, educate and eradicate TB

Universal Immunization Program: An initiative to provide children and families in Mumbai with

proper immunizations

Polio Eradication Program: To immunize, treat, and eradicate Polio

National Malaria Control Program: To address and treat Malaria

Mumbai District AIDS Control Society: Educate, disseminate information, provide counseling

and treatment, blood safety, monitoring and evaluation

School Health Program: The SHP aims to provide in school health care for children attending the

schools run by the MCGM

Successes

Managing such a complex system of health infrastructure has yielded successful initiatives. The

School Health Program and Polio Eradication Programs are 2 of them. The main reasons for

success can be communicated through de-centralization of management, networking with

families, creating community understanding around a certain illness and strong leadership.

Among these few successes, there are many areas that need to be improved throughout the

MCGM public health system.

Challenges

All of the aforementioned programs are run in synergy through the jurisdiction of the Public

Health Department. Many of the reasons the public chooses not to access the care is:

The MCGM Health Budget: The budget of the MCGM Health Department (over Rs. 800 Crores)

lacks equity in terms of distribution of resources to the secondary and primary levels of care

Primary health care services are weak in resources and manpower, this leads the general public

to seek healthcare at the tertiary level of care

Secondary Hospitals and Maternity Care are also not well-equipped and suffer from centralized

decision making systems that prevent administration for taking decisions

Tertiary Hospitals are on the receiving end of the high monetary assistance and have to bear the

burden of overcrowding and higher expectations of patients due to the weakness in the secondary

and primary care systems

Inconvenient timings, locations, and a high amount of vacancies have lead to a great degree of

dissatisfaction with the MCGM run services

Lack of emphasis on quality assurance results in apathy from staff as well as patients

Lack of referral systems also lead to a misunderstanding of which services are offered where and

create too much of a free market system for patients that results in overcrowding at the tertiary

level

Reporting and data collection, as evident from the Mumbai health profiles needs to be improved

and expanded with up to date data as well as accurate descriptions of rationale

Competition from the private sector (practitioners and hospitals) also poses a considerable barrier

for underprivileged folks to access the public health system

Lack of public health disaster systems as well as adequate water sanitation and supply also

contribute to problems in access to health care

Overall, the report looks at various successes and challenges of the MCGM public health system.

Through there are many challenges, the good news is that Mumbai has an existing infrastructure

that can contribute to the improvement of how people in the city access the public health care

system. This report gives various recommendations in terms of:

Education and Information Dissemination

Reproductive and Child Health

Medical and Administrative Personnel

Infrastructure

Systems

Coordinating with other MCGM departments

Priorities in Health

The primary step that will be taken will be the initiation of a Bill of Rights for Patients as well as

a Code of Conduct to help education and inform people accessing ALL health care in Mumbai as

to what their rights are and what the expectation is of their behavior.

This report serves as an initial document to signify the NGO Council’s and the MCGM’s

commitment to the health care of the people of Mumbai. This document can be utilized by

practioners, administration teams, doctors, nurses, medical students, NGOs and more. An indepth analysis of the MCGM’s health care system can give all those involved in the field some

insight into the inner workings of Mumbai’s premier public health system in addition to citing

specific areas for improvements. A healthier community can contribute to the overall wealth of

Mumbai, making it healthy, wealthy, and wise.

Accessing Healthcare in Mumbai

Conclusions and Summary

In the last 20 years, there have been few initiatives proposed to improve health for the citizens of

India. When looking at the policies and initiatives proposed by the Central Government, there is

a clear emphasis on improving rural health. However, with the urban poor population rising, the

health needs of the urban poor communities are beginning to exceed those in the rural

communities. The health care crisis of the growing urban poor, especially in Mumbai, represents

a new challenge in providing health care to the masses. The health care of the urban poor is often

worse than or equal to that of the rural poor population. Over 50% of Mumbai’s population of 18

million[23] lives in slums and are part of the growing urban poor. This population is plagued with

uneven access to care, malnutrition, and poor maternal and child health. Therefore, it is critical to

look at the health of Mumbai on a continuum of urban health.

The MCGM (Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai) provides medical services through

three levels of care, primary, secondary and tertiary. This includes an intricate network of

teaching hospitals, secondary hospitals, maternity homes, health posts and dispensaries.

Although the infrastructure is complex, there is a multitude of improvements needed to address

the health needs of the urban poor population in Mumbai. The various challenges plaguing the

MCGM health system are growing as rapidly as the population and need to be addressed

urgently. The challenges include:

Human Resources: A large amount of vacancies in the public health department of the MCGM

lead to the apathy of the staff and patients.

Infrastructural: Lack of equipment and services at the primary and secondary level of care; lack

of referral systems to direct patients to the appropriate care level; lack of quality assurance

Systems: Lack of a centralized data system, lack of awareness of existing programs within the

MCGM

Ethical: Dilution of the value and faith in the public health system as a facility for all, not just the

indigent and underprivileged. This is a phenomenon that affects the patients as well as the staff.

Educational: Educational materials for prevention of disease and promotion of health are underutlilized or unavailable, patients do not understand the complexities of their own health

With a confident team, collaborations, and an open attitude toward change, there are many

options for the MCGM health system to become an accessible service for people seeking quality

health care at an affordable price. A no-frills health care system that emphasizes good quality at

the lowest possible cost to the consumer will not only benefit the poor, but also those taxpayers

whose money is being invested in the government run health care system. Working with existing

private providers and NGOs can be beneficial for the MCGM system in terms of decreasing the

burden and using best practices of existing programs.

Utilizing best practices from cities with similar problems to Mumbai will provide some insight

into innovations that could be implemented throughout the existing health systems. While the

problems sometimes seem to vast to deal with, it is important to remember that an

implementation strategy that works on a step-by-step approach will be the ideal method of

slowly improving the system. The MOU between the NGO Council and the MCGM is the

critical agreement that should be kept in mind in the difficult stages of planning and

implementation. This agreement is meant to bridge the gap between the government and the non

profit organizations that provide many needed services to the impoverished. Both have similar

goals, it is now time to devise a better strategy through collaboration.

Recommendations- Brief

A. Education and Information Dissemination

Ensure that a Patient Bill of Rights (enclosed) and Patient Code of Conduct are posted in every

public health care facility being operated by the MCGM

Create a map of Mumbai (in Hindi, Marathi, English, etc) with locations, timings, and services of

each healthy care facility.

Improve primary and secondary health care systems by providing training for quality assurance

at all facilities.

Ensure that educational materials on ALL illnesses and ailments are available in multiple

languages at respective primary and secondary health care levels via posters, pamphlets, and

CHVs.

B. Reproductive and Child Health

Increase awareness about institutional deliveries by collaborating with local women’s groups.

Develop IEC materials relevant to reproductive and child health as well as other relevant

diseases by working with NGOs

Ensure all maternal, reproductive and child health services are free of cost.

Ensure that all municipal facilities are always stocked with medications for pre-natal care (iron,

folic acid etc.)

C. Medical and Administrative Personnel

Increase skills, salaries, and working hours of the Community Health Volunteers and have

CHV’s collaborate with health workers from NGOs

Discontinue the practice of allowing doctors to have private practices while employed by the

MCGM.

De-centralize the management of the primary and secondary health care services

D. Infrastructure

Hire staff to fill vacancies of doctors at the primary health care level (Health Posts and

Dispensaries) to improve the quality of care

Conduct a needs assessment of the infrastructural (both equipment, human resources) gaps in the

MCGM public health system via a survey and analysis to apply appropriate solutions.

Decrease the gaps in infrastructure (staff, equipment, and training) at the primary and secondary

levels of health care

Create a referral system so that people can access the medical services at the appropriate lowest

level.

Utilize the referral system to minimize costs, patient load, and provide better quality treatment

for serious cases.

Create management information systems to store and utilize data, statistics, and health records

appropriately.

Create systems for MCGM circulars to be accessible to all

Revamp the ambulatory system completely to provide emergency care as well as transport.

De-centralize the laboratory system. Ensure all peripheral hospitals have functional labs.

E. Systems

Create a patient feedback system to improve policies, procedures, and services for patients and

for MCGM staff.

Create a Public Health Monitoring Department that meets once in 2 months to plan for upcoming

public health issues (i.e. bird flu, leptospirosis).

F. Coordinating with other MGCM Departments

Introduce adolescent health education through the municipal school system.

Increase citizen participation through a public health citizen committee in collaboration with the

MCGM public health department.

Improve disaster management to minimize public health outbreaks

Improve water supply and sanitation at all slums, this will decrease the amount of diseases in the

area.

G. Priorities in Health

Create a department that addresses issues of respiratory health in Mumbai, this should also be a

division of the school health department

Utilizing the existing DOTS program, increase the priorities of TB management

Implement more programs focused on decreasing IMR and MMR (these should be focused on

nutrition, education, and health of the mother as well as the child)

Create a city-wide campaign regarding Malaria awareness to be promoted during and before

Malaria months

Ensure that all vitamins and supplements are available to NGOs distributing them to children

through various programs

1. Introduction and Background

Through an initiative between the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM) and the

NGO council in Mumbai, health was identified as a major priority. This policy report was

written in order to have a better perspective on health in Mumbai. The NGO Council is a

representing body of NGOs in Mumbai seeking to collaborate with local authorities on issues of

priority. The NGO council was formed on August 22, 2005. The Council is comprised over 70

organizations with complementary expertise covering all causes and sectors. The primary

objectives of the NGO council is to work with Government, Donors, NGOs, and other thirdparties to raise awareness and convene to address the important issues effecting the city of

Mumbai.[24] On 12/12/2005, Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM) has entered

into an MOU with the NGO Council, recognizing that an institutionalized partnership between

municipal bodies and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) / civil society organizations

(CSOs) is critical for promoting Good City Governance. [25]

The MCGM was formed in 1873 as Mumbai’s civic body. Through the multifarious civic and

recreational services that it provides, the MCGM has always been committed to improve the

quality of life in Mumbai.[26] It was under this spirit that the MCGM and part of their team took

the initiative to come into an agreement of partnership with the NGO Council. The MCGM has

signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the NGO Council to begin to discuss the critical

issues, one of the major ones being health.

The general responsibilities in Public Health for the MCGM are specified on the website:

Public Health and Medical Relief Services[27]

The following functions are performed by the staff in the wards under the supervision and

guidance of the Executive Health Officer, the Deputy Executive Health Officer, 4 Zonal

Assistant Health Officers and the Epidemiologist.

1. Prevention and control over communicable diseases.

2. Maintenance of vital statistics regarding births, deaths and occurrence of diseases.

3. Maternity and child welfare services.

4. Medical relief through dispensaries including mobile dispensaries.

5. Regulation of the places for the disposal of the dead.

6. Prevention of adulteration and misbranding of articles of good.

7. Licensing and controlling trades dealing in food and coming under the purview of sections 394

and 412A of the Bombay Municipal Corporation Act

8. Licensing and controlling trades (Other than food establishments)

9. Controlling places of public amusement from public health point of view, namely, cinema

houses, drama theatres, etc.

10. Registration and inspection of Nursing Homes.

11. Licensing of Nurses Establishments.

12. Expansion programme of public health and medical relief services.

13. Other miscellaneous functions

For the efficient discharge of these functions, Greater Bombay has been divided into Wards

which, have been grouped into six zones. Each zone is in charge of each of four Assistant Health

Officers. The table below is an organogram of the current hierarchy at the MGCM Public Health

Department.

Table 1.1 Organogram for the MCGM Public Health Department

For the purpose brevity and focus of this report, we have chosen to focus on very specific aspects

of health care and delivery systems. This includes primary health centers, peripheral hospitals,

maternity homes, health posts, dispensaries; communicable, non-communicable and infectious

diseases; health and hygiene, sanitation, access to water, and environmental health. This report

will exclude registrations of births and deaths, stray cattle, disposal of the dead, and such issues

such as licensing. While all issues are important, this report will only cover the aforementioned

issues as they are directly linked with access to public health care facilities.

2. National Policies in Health Care in India

This section will identify the various policies that have come in surrounding health care

initiatives in India. It is important to look at the national initiatives before we focus on Mumbai,

because these policies can provide the MCGM and the NGO Council with some insight on

national health policy standards and how good governance can help the city move forward to

adherence.

2.1 National Health Policy

The Government of India (GOI) first drafted a National Health Policy in 1983 (NHP-1983). This

policy was created to set a primary objective of Health Care for All by 2000. The establishment

of efficient and effective primary health care systems, especially for the vulnerable: the

underprivileged, women, and children were critical elements of achieving health care for all by

2000. The GOI had set an ambitious agenda for improvement of health of the Indian citizen.

An integrated network of evenly spread specialty and super-specialty services was specified in

the draft. Since implementation of NHP-1983, the national health program was able to achieve

some successes in health care. Smallpox and Guinea Worm Disease have been eradicated from

the country; Polio is on the verge of being eradicated; Leprosy, Kala Azar, and Filariasis can be

expected to be eliminated in the foreseeable future. There has been substantial drop in the Total

Fertility Rate and Infant Mortality Rate. The life expectancy has gone from 36.7 to 64.6 in 50

years. The Infant Mortality Rate (IMR) has been cut in half since 1951. The success of the

initiatives taken in the public health field are reflected in the progressive improvement of many

demographic / epidemiological / infrastructural indicators over time – (Table 2.1).[28]

Table 2.1 : Achievements Through The Years - 1951-2000[29]

Indicator

1951

1981

2000

Life Expectancy

36.7

54

64.6

Crude Birth Rate

40

33

26

Crude Death Rate

25

12

8

IMR

146

110

70

Demographic Changes

Epidemiological Shifts

Malaria (cases in million)

75

2

2

Leprosy cases per 10,000

population

38

57

4

Small Pox (no of cases)

>44,887

Eradicated

Guineaworm ( no. of cases)

>39,792

Eradicated

Polio

29709

265

Infrastructure

SC/PHC/CHC

725

57,363

1,63,181

Dispensaries &Hospitals( all)

9209

23,555

43,322

Beds (Pvt & Public)

117,198

569,495

8,70,161

Doctors(Allopathy)

61,800

2,68,700

5,03,900

Nursing Personnel

18,054

1,43,887

7,37,000

The table above highlights the progression of health infrastructure, demographics, and

epidemiology through 50 years.

These achievements only represent a fraction of the need that exists in India. Ironically, with a

hike in user charges, proposals of privatization of government hospitals, and increasing

healthcare costs, the year 2000 represented a dynamic turn in the intended goals of NHP1983.[30] The burden of cost of care subsequently has shifted from being the responsibility of the

government to becoming a burden on the patient seeking care. A retrospective analysis of the

NHP-1983 alludes to the fact that the policy may have been over ambitious considering the

infrastructure that existed at that time.

The next National Health Policy was written in 2002, when public health investment was at an

all time low, 1.3% of the GDP in 1990 to .9% of the GDP in 1999 (GOI, 2002). The aggregate

expenditure in the Health sector is 5.2 percent of the GDP. Out of this, about 17 percent of the

aggregate expenditure is public health spending, the balance being what ends up being out-ofpocket expenses.[31] The central budgetary allocation for health over this period, as a percentage

of the total Central Budget, has been stagnant at 1.3 percent, while that in the States has declined

from 7.0 percent to 5.5 percent. The current annual per capita public health expenditure in the

country is no more than Rs. 200.[32]

Table 2.2: Public Health Spending in select Countries[33]

%Population

with income

of <$1 day

%Health

Expenditure

to GDP

%Public

Expenditure on

Health to Total

Health

Expenditure

India

44%

5%

17%

China

19%

3%

24%

Sri Lanka

7%

3%

45%

UK

-

6%

97%

USA

-

14%

44%

The table above demonstrates the public health spending in select countries. India, China, and

America spend the least amount on their public health expenditure.

These statistics indicate why we are at quality level that does not deliver services at a desirable

standard. Under the constitutional structure, public health is the responsibility of the States. The

general expectation is that the State will give the principal contribution to public health care,

with the supplemental support from the Central government.

In this backdrop, the contribution of Central resources to the overall public health funding has

been limited to about 15 percent. According to NHP 2002, the fiscal resources of the State

Governments are known to be very inelastic. This is reflected in the declining percentage of State