Wake Forest-Moir-Brown-Neg-Districts-Round1

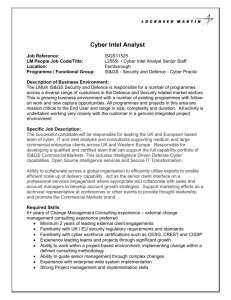

advertisement