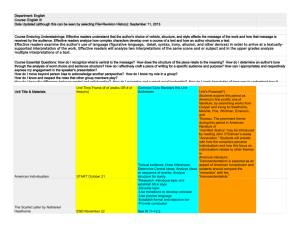

Critique of Radical Autonomy

advertisement