Spirometry - American Academy of Family Physicians

advertisement

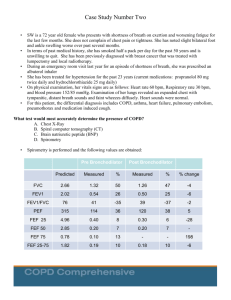

COPD: Spirometry Clare Hawkins, MD, MS Program Director, San Jacinto Methodist Hospital Family Medicine Residency, Baytown, TX Isaac M. Goldberg, MD Faculty, San Jacinto Methodist Hospital Family Medicine Residency, Baytown, TX Educational Objectives At the end of this presentation, the learner should be able to … • Utilize spirometry to diagnose and stage COPD • Overcome barriers to the use of office spirometry • Achieve confidence with spirometry interpretation Background Objective measure of airway function for accurate diagnosis of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) World Health Organization Global Obstructive Lung Disease Consensus/ Evidence guideline (GOLD) American Thoracic Society (ATS) European Respiratory Society (ERS) National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) Background Alternate ways to diagnose COPD Clinical Findings Late - Increased AP diameter, tympanitic chest - Signs of respiratory distress Peak flow reading not adequately sensitive or specific Radiographic findings occur late in disease CT scanning more accurate, but findings also occur late in disease Background Who should receive spirometry? Early diagnosis relies on the recognition of the clinical features - Persistent cough Chronic sputum production Breathlessness on exertion Reduction in activity (often attributed to natural aging) About 20% of COPD patients identified in NHANES study with obstruction never smoked - Only 1/5 were explained by asthma Background Other testing considerations Recurrent or chronic respiratory symptoms Occupational exposure to respiratory irritants Family history of respiratory diseases and symptoms NCQA established use of spirometry as required quality measure for accurate COPD diagnosis Routine periodic use not recommended Background Screening Not recommended in the absence of respiratory symptoms (dyspnea, cough) No threshold amount of smoking pack-years for screening in the absence of respiratory symptoms Not recommended by USPSTF or ACP 2011 Guideline Background Family physicians able to do quality spirometry Quality of care increases with use of spirometry - To prevent overdiagnosis of COPD, attention to quality spirometry is important Suggestions to maintain quality of spirometry - Know technique Have staff coach the patient Do sufficient numbers of tests Maintain and calibrate the equipment Understand interpretative algorithms Background Why do office spirometry? Diagnostic accuracy. 30% of time diagnosis changes. - Was not COPD; heart failure or asthma - Was COPD rather than asthma - If spirometry normal, then expensive meds discontinued Respect. Patients respect physicians who use technology (Future of Family Medicine) Patient convenience. You can avoid an unnecessary referral and additional visit Diagnostic power: You can connect diagnostic information with rest of clinical encounter Financial benefit to practice. Equipment Older volume/time loop - Drum technique from John Hutchinson 1844 Newer flow/volume loop using flow transducer - Smaller Machines, Mobile - Disposable Mouthpiece No other infection transmission precautions necessary Equipment Numerous manufacturers produce quality instruments Reviews conducted by National Lung Health Education Program (NLHEP) regarding appropriateness of spirometers for office practice - http://www.nlhep.org/spirometer-review-process.html - Simplicity (fewer numbers) - Reliability Equipment Calibration Daily calibration must be done with 3 L syringe Syringe must have accuracy of at least 15 ml Spirometer must have accuracy of ±105 mL or 0.105 L (calibration volume = 2.90 to 3.11) Calibration log/printouts must be kept - Date and time of calibration - Individual performing - Comments Technique Forced expiratory maneuver Coach patient to get a maximal effort Six seconds of effort required though most of air pushed out in the first second Pace of expired air is most important variable; therefore it should be released with explosive force Technique Minimum 6 second exhalation with 2 second plateau Tracing should have no artifacts At least 3 acceptable maneuvers (<5 % variation) - ATS criteria Empty bladder for females (concern if incontinence) Can be seated or standing Nose plug optional Technique None of the following should occur: Unsatisfactory start, with excessive hesitation or false start Air leak Coughing during the first second Early termination of forced expiration Glottis closure Obstructed mouthpiece - Tongue - False teeth - Chewing gum Technique Reliability Spirometry overdiagnoses COPD if insufficient effort Concerns that family physicians will not perform quality testing and overdiagnose people with obstructive lung disease Imperative that patients be coached on robust, forced expiratory maneuver Technique Contraindications Hemoptysis of unknown origin Pneumothorax Unstable cardiovascular status or recent MI or PE Thoracic, abdominal, or cerebral aneurysms Recent eye, thorax or abdomen surgery Technique Barriers Inaccessibility of Equipment Concern patient effort and cooperation are insufficient Difficulty remembering interpretive algorithm Frustration by ambiguous results Difficulty working 30-minute spirometry into office flow Central location for spirometry versus going room to room Lack of staff training Poor integration with electronic health record Lack of adequate reimbursement Measurements Abbreviation Characteristic measured FEV1 Forced expired volume in 1 second FVC Forced vital capacity FEV1 /FVC Ratio Ratio of the above PEFR Peak expiratory flow rate FEF 25-75% Forced expiratory flow between 25-75% of the vital capacity Measurements Normal values Individual variation according to age, height, ethnicity and gender - Height - Tall people have larger lungs Age - Respiratory function declines with age Sex - Lung volumes smaller in females Race - Studies show Blacks and Asians have smaller lung volumes (-12%) - Posture - Little difference between sitting and standing; reduced in supine position Measurements Bronchodilator reversibility testing Beta-agonist - Short-acting – wait 20 minutes before retesting - Long-acting – wait 2 hours before retesting Do not take bronchodilator the day of testing - Measured reversibility will be limited if the patient is bronchodilated for the pretest. Measurements Definition of reversibility Pre-Bronchodilator - FEV1/FVC <70% of predicted Post-Bronchodilator - Increase 12% AND at least 200 cc Reversibility = Asthma! Measurements Pre-Bronchodilator Post-Bronchodilator Predicted Measured % Measured % % change FVC 2.66 1.32 50 1.26 47 -4 FEV1 2.02 0.54 26 0.50 25 -6 FEV1/FVC 76 41 -35 39 -37 -2 PEF 315 114 36 120 38 5 FEF 25 4.96 0.40 8 0.30 6 -28 FEF 50 2.85 0.20 7 0.20 7 ----- FEF 75 0.78 0.10 13 ----- ----- 198 FEF 25-75 1.02 0.19 10 0.18 10 -6 Measurements Severity of obstruction FEV1 Mild Moderate % of predicted >80 50 to 79 Severe 30 to Very severe <30 Severity of restriction FVC % of predicted Mild >65 to 80 Moderate >50 to 65 Severe <50 Case Study 1 A 53-year-old white male presents for annual visit. Although he quit 10 years ago he is a previous cigarette smoker with a 20 pack-year history. During the past 12 months, he has had 3 episodes of bronchitis. His history of tobacco use and recent episodes of acute bronchitis lead you to perform spirometry. Results Pre-Bronchodilator Post-Bronchodilator Predicted Measured % Measured % % change FVC 4.65 4.65 100 4.95 106 6 FEV1 3.75 3.13 83 3.34 89 6 FEV1/FVC 80 67 -13 67 -13 0 PEF 511 462 90 522 102 12 FEF 25 7.86 5.7 73 6.00 76 5 FEF 50 4.46 2.3 52 2.10 47 -9 FEF 75 1.75 .5 29 0.60 35 18 FEF 25-75 3.76 1.77 47 1.78 47 0 Results Pre-Bronchodilator Post-Bronchodilator Predicted Measured % Measured % % change FVC 4.65 4.65 100 4.95 106 6 FEV1 3.75 3.13 83 3.34 89 6 80 67 -13 67 -13 0 FEV1/FVC Is there obstruction? FEV1/FVC = 67% of predicted; therefore, obstruction present Is there restriction? FVC = 100% of predicted; therefore, no restriction present Results Pre-Bronchodilator Post-Bronchodilator Predicted Measured % Measured % % change FVC 4.65 4.65 100 4.95 106 6 FEV1 3.75 3.13 83 3.34 89 6 80 67 -13 67 -13 0 FEV1/FVC What is the severity of obstruction? FEV1 is 83% of predicted; therefore, the obstruction is mild Is the obstruction reversible (is reversibility present)? FEV1 increases from 83% to 89% (6% increase) and increases from 3,130 cc to 3,340 cc (increase of 210 cc) Interpretation: Mild Obstruction with minimal reversibility: Mild COPD Common Obstructive Pulmonary Disorders Diffuse Airway Disease Upper-Airway Obstruction Asthma COPD Bronchiectasis Cystic fibrosis Foreign body Neoplasm Tracheal stenosis Tracheomalacia Vocal cord paralysis Diagnostic Flow Diagram for Obstruction Is FEV1 / FVC Ratio Low? (<70%) Yes Obstructive Defect Is FVC Low? (<80% pred) Yes No Combined Obstruction & Restriction /or Hyperinflation Pure Obstruction Improved FVC with ß-agonist Reversible Obstruction with ß-agonist No Further Testing with Full PFT’s Yes Yes Suspect Asthma No Suspect COPD Adapted from Lowry. Case Study 2 A 33 year old female presents to the office complaining of dyspnea and cough for the past 2 days. Her cough is productive of a white mucous. Her past medical history is significant for asthma since childhood, obesity, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and an occasional migraine headache. She is a nonsmoker and has no known allergies. Case Study 2 (cont) Her current medications include the following: Albuterol 2 puffs po qid prn wheezing, cough, or dyspnea Fluticasone 110 micrograms 2 puffs po bid Ranitidine 150 mg po bid Her father recently died secondary to advanced COPD. Due to her symptoms, you order spirometry. Results Pre-Bronchodilator Post-Bronchodilator Predicted Measured % Measured % % change FVC 3.78 1.92 51 2.7 71 34 FEV1 3.24 1.11 34 1.61 50 36 86 58 -28 60 -26 3 FEV1/ FVC Obstruction? FEV1/FVC = 60%; therefore, obstruction present Restriction? FVC = 51% of predicted; therefore, restriction present Results Pre-Bronchodilator Post-Bronchodilator Predicted Measured % Measured % % change FVC 3.78 1.92 51 2.7 71 34 FEV1 3.24 1.11 34 1.61 50 36 86 58 -28 60 -26 3 FEV1/ FVC What is the severity of obstruction? 60%; therefore, moderate obstruction Is the obstruction reversible (is reversibility present)? FEV1 increases from 34% to 50% (16% increase) and increases by 500 cc What is the severity of restriction? 71% of predicted; therefore, mild restriction Interpretation: Moderate obstruction with reversibility (Moderate obstruction) Common Restrictive Pulmonary Disorders Parenchymal Pleural Interstitial Lung Diseases - Fibrosis Granulomatosis (TB) Pneumoconiosis Pneumonitis (lupus) Loss of Functioning Tissue - Atelectasis Large Neoplasm Resection Effusion Fibrosis Chest Wall Kyphoscoliosis Neuromuscular Disease Trauma Extrathoracic Obesity Abdominal Trauma Diagnostic Flow Diagram for Restriction Is FEV1 / FVC Ratio Low? (<70%) No Is FVC Low?(<80% pred) Yes Restrictive Defect Further Testing with Full PFT’s; consider referral if moderate to severe No Normal Spirometry Adapted from Lowry, 1998 Results Lowry 1998 Results “Full” Pulmonary Function Testing (PFT’s) Assessment of Oxygenation - Transcutaneous oxygen saturation - Arterial blood gasses Diffusion test to evaluate alveolar exchange (DLCO) Plethysmography - To objectively assess lung volumes - Delineate air-trapping versus restriction May also include Spirometry Spirometry and Smoking Cessation Lung age calculation - Use to motivate smoking cessation. Mixed results - Normal results may give the impression that it’s acceptable to continue smoking. - Avoid fatalism with abnormal results. Research results recently favor use - ACP and AHRQ advise only if symptomatic. Spirometry and Smoking Cessation Spirometry and Smoking Cessation Coding and Reimbursement Diagnosis ICD-9 Code Cough 786.2 Simple chronic bronchitis 491.0 Mucopurulent chronic bronchitis 491.2 Acute bronchitis 466.0 Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 496.0 Shortness of breath 786.5 Restrictive lung disease Asthma 515 493.91 Coding and Reimbursement Procedure CPT Code Reimbursement* Single spirometry 94010 $32.82 Pre-post spirometry 94060 $57.71 Pulmonary stress test simple 94620 $71.77 Medication administration bronchodilator supply separate 94640 $13.34 Demonstration / instruction 94664 $14.79 Smoking Cessation <8x/ yr 99406 $12.98 Equipment Office spirometer *Reimbursement based upon Medicare payments 2009 Cost $1,000 – 2,500 Estimated Return on Investment Tests /week (#) Reimbursement/year* ROI $1,995 in weeks 4 $6,864 15 6 $10, 296 10 8 $13,728 7 10 $17,160 6 15 $25,740 4 20 $34,320 3 25 $42,900 2 *Based upon CPT code 94010 References • • • • • • • AARC Clinical Practice Guideline. Delivery of aerosols to the upper airway. Respir Care 1996;41(7):629-36 Belfer M. Office management of COPD in primary care: A 2009 clinical update. Postgraduate Medicine 2009;121(4):82-90. Blain EA, Craig TJ. The use of spirometry in a primary care setting. Int J Gen Med. 2009; 2: 183–186. Chavez,P.C. and Shokar,N.K. Diagnosis and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in a primary care clinic. COPD 2009;6(6): 446-451. Enright P. The use and abuse of office spirometry. Prim Care Respir J. 2008 Dec;17(4):238-42. Fletcher C, Peto R. The natural history of chronic airflow obstruction. Br Med J. 1977;1(6077):1645-1648. Ferguson GT et al. Office spirometry for lung health assessment in adults: A consensus statement from the National Lung Health Education Program. Respiratory Care 2000;45(5) 513-30 References (continued) • • • • • • Grossman E, Sherman S. Telling smokers their "lung age" promoted successful smoking cessation. Evid Based Med. 2008;13(4):104 Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general US population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;159:179–187 History Diagnosis Spirometer http://www.umanitoba.ca/libraries/units/health/images/HistoryDiagnosisSpir ometer.jpg Jing JY. Should FEV1/FEV6 replace FEV1/FVC ratio to detect airway obstruction? A metaanalysis. Chest. 2009 Apr;135(4):991-8. Johannessen A, et al. Post-bronchodilator spirometry reference values in adults and implications for disease management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 173(12):1316-25. Kaminsky DA, Marcy TW, Bachand M, Irvin CG. Knowledge and use of office spirometry for the detection of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by primary care physicians. Respir Care. 2005 Dec;50(12):1639-48. • • • • • • Knudson RJ, Slatin RC, Lebowitz MD, Burrows B. The maximal expiratory flow-volume curve. Normal standards, variability, and effects of age. Am Rev Respir Dis 1976;113:587–600 Lin KW Screening Spirometry. American Family Physician 2009;80(8) :8612. Lowry, Josiah A Guide to Spirometry for Primary Care Physicians 1998 Published by College of Family Physicians of Canada with Boehringer Ingelheim MacIntyre NR, Selecky PA. Is there a role for screening spirometry? Respir Care. 2010;55(1):35-42 [Review]. National Committee on Quality Assurance. 2009 Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) performance measures. 2010. Available at www.ncqa.org/tabid/855/Default.aspx. Accessed August 2010. Parkes G, Greenhalgh T, Griffin M, Dent R. Effect on smoking quit rate of telling patients their lung age: the Step2quit randomised controlled trial BMJ 2008;336:598-600. References (continued) • • • • • • Poels PJ, olde Hartman TC, Schermer TR. Qualitative studies to explore barriers to spirometry use: a breath of fresh air? Respir Care. 2006 Jul;51(7):768. Rennard S, Vestbo J. COPD: The Dangerous underestimate of 15%. Lancet 2006; 367, 1216-1219. Spann SJ. Impact of spirometry on the management of chronic obstructive airway disease. J Fam Pract. 1983 Feb;16(2):271-5. Spirometer Review Process (SRP) – Revised. http://www.nlhep.org/spirometer-review-process.html. Accessed, November 14th, 2010. Wilt TJ, Niewoehner D, Kim C, et al. Use of spirometry for case finding, diagnosis, and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ). 2005;(121):1-7 [Review]. Yawn BP et al. Spirometry can be done in family physicians' offices and alters clinical decisions in management of asthma and COPD. Chest. 2007 Oct;132(4):1162-8. Epub 2007 Jun 5.