The Market for Independent Directors

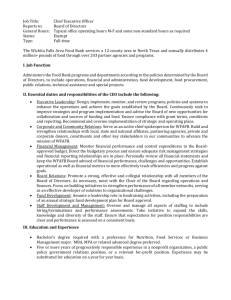

advertisement