COMMERCE IN MEDIAVEL

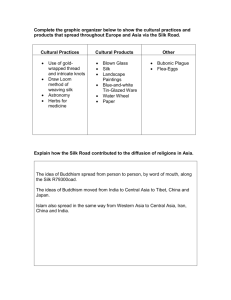

advertisement

INTRODUCTION Medieval trade and exchange affected not just merchants and the governments that taxed and regulated them. Trade within a country or culture and trade with people of other lands affected almost everyone. The open, protected trade routes fostered by the early Islamic world, for example, were essential to the agricultural boom that began in the 700s. Still, trade was about more than bringing food to market. Underlying trade was people’s desire to purchase goods not to be found locally; merchants who understood what their markets wanted could prosper. The most spectacular examples of this in the medieval world were probably the trade in silk and the trade in spices. Silk was a product that drove much international trade in Asia before the medieval era. In the early medieval period China sought to militarily dominate the trade routes of central Asia, out of a desire to ensure that the trade routes for its silk remained open. In the Near East and Europe governments tried to learn the secret of making silk; when they did, they began silk-making industries in their own lands. In this were elements of modern trade and exchange, because not all silk was equal in quality. The Silk Road represents an early phenomenon of political and cultural integration due to inter-regional trade. The route experienced its prime periods of popularity and activity in differing eras at different points along its length. The Middle Ages saw the rapid expansion of Medieval trade and commerce. The most important factor in the expansion of trade and commerce were the Crusades. The Crusades, which had facilitated the relations with Eastern countries. THE SELJUKS and EUROPEAN TRADE The Seljuk were a Turkish dynasty that ruled parts of Central Asia and the Middle East from the 11th to 14th centuries. They established an empire, the Great Seljuq Empire, which at its height stretched from Anatolia through Persia and which was the target of the First Crusade. Developed a taste in the West for their indigenous productions, gave a fresh vigour to this foreign commerce and trade, and rendered it more productive by removing the stumbling blocks which had arrested its progress. Two Islamic men on a silk trade route with camels Picture of medieval merchants meeting a trade ship at the local dock. Local manufacture of goods was highly encouraged by the Seljuks. The many Christian Greek and Armenian businessmen and merchants present in Anatolia at the arrival of the Turks were allowed by them to continue living and working in their towns. They formed a very active sector of economic importance in the areas of metalwork, textiles, and construction, and even taught these trades to the Seljuks. By the second quarter of the 13th century the Seljuks had become an export nation, although they still imported more that they exported. They had also developed many local industries and traded their own goods among the cities of the Empire. These industries included the production of alum (an important mordant for dyeing wool) and refined sugar. Parallel to this mercantile activity inland was an extensive shipping trade, based in the ports of Antalya and Alanya on the Mediterranean and in Sinop on the Black Sea. The capture of Antalya in 1207 had signaled a major triumph for the Seljuks, as it opened trade with Europe. The capture of Alanya in 1221 was an even greater asset, as the natural harbor provided the opportunity to set up a naval base in addition to the establishment of commercial activities, notably with Florence and France. The bulk of the trade was of a transient nature. Major trading originated in the cities of Konya, Sivas and Kayseri, and was often handled in these urban centers by Greeks and Armenians. In a later time, the Venetians and merchants of Constantinople set up elaborate trade agreements, notably for luxury items such as textiles and gems. Trade was also maintained with the east to Syria and Iraq, as well as with the Kipchak Empire of Southern Russia via the active port of Sinop. Depiction of a medieval market fair with round topped stalls from which livestock, textiles, and household tools are being sold. Patterns of trade were varied. Merchants bought and sold along the way, bumble-bee style, or drove specific convoys of goods to a specific client, urban market or port of call. Trade went on inside of the han as well, where merchants could meet with local clients and negotiate prices and orders. The Turks were heavy exporters, and sent out more goods than they imported. In addition to the tin, alum and other goods mentioned above, what exactly was sold along these routes? What was unloaded from the tired camels tethered at the end of the day in the courtyards of the great Anatolian hans? Many of these items could eventually have made their way to Europe as well, transported by the Latins and Byzantines from the maritime ports of Antalya, Alanya and Sinop. What did they export? sugar from the refineries of Alanya soap thoroughbred horses livestock produce: fruits (notably apricots), grains, olives, wheat, salted fish textiles and carpets dried wheat chemical and mineral compounds: alum, salt, borax, yellow arsenic orpiment ("King's yellow" arsenic trisulfide pigment). Alum, an essential mordant for dyeing wool, was a particularly important export. metals: silver, lead, tin, zinc, copper, iron lapis lazuli leather, wool, mohair gum Arabica, pine resin, timber slaves, taken captive in war or raid, usually supplied by the Kipchaks. Slaves appeared to be the most valuable commodity of the Black Sea route. The Seljuks were the middlemen in the trade of slaves. Circassians and Kipchaks of Southern Russia were sold in the great markets of the Crimea to the Egyptians who imported them to become Mamluk slave servants. Mail, and documents of official and governmental nature were also transported along these routes. Venetian and Genoese merchants set up prosperous trading posts on the Black Sea that benefited from a flow of goods from central Asia. These merchants traded for spices, silk and luxury goods with slaves, iron, wine, light wool, linen and metal wares. European wines from Italy, France and Germany were highly prized, but it was European wool, linen and other textiles that were particularly valued. England, the Netherlands and northern Italy produced high quality woolen cloth in various luxurious weaves using technology unknown outside of Europe. Similarly, European linen was another sought after import.