Porter's alternative generic strategy is differentiation

advertisement

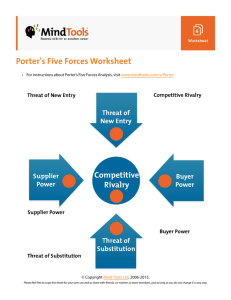

DEVELOPING STRATEGIC DIRECTION: CAN GENERIC STRATEGIES HELP? Porter argues that careful analysis of the competitive arena by use of his five forces model will help firms to select the competitive strategy that will allow them to achieve 'sustainable competitive advantage'. Readers unfamiliar with the five forces model are referred to our article in the November 1993 issue.[2] If we look at Porter's generic strategies matrix (Figure 1) it can be seen that he offers two alternative routes to competitive advantage: cost leadership and differentiation Cost leadership means that the firm achieves--or seeks to achieve--the status of lowest-cost producer or supplier to its market. A frequent misconception is that this means lowest price supplier and one can find commentators citing Kwik Save or Skoda as examples of this strategic stance. The lowest-cost producer has the ability to price below competitors but, while this provides a cushion in times of severe price competition, to do so gives away the profit margin advantage that is available. As Porter: says: 'Its cost position gives the firm a defence against rivalry from competitors, because its lower costs mean that it can still earn returns after its competitors have competed away their profits through rivalry'. A cost leader may accept average market prices, i.e. it can maintain price parity with its competitors and this will lead to superior profitability. Pursuit of a cost-leadership strategy may frequently require a strong focus on cost management, scale economies and experience curve cost advantages through maintenance of volumes. Sharp[3] distinguishes between true cost advantage and one derived from delivering fewer benefits, i.e. differentiating downwards. Certainly if a lowest-cost competitor can maintain parity with the competition by offering an attractive set of product attributes, it obtains profit advantage. If it offers fewer differentiating attributes at a lower price, then-its ability to generate above-average profits will depend on its ability to manage its cost base. Porter argues that there can be only one cost leader in a market. This assertion is debatable. Faulkner and Bowman[4]' cite empirical studies which have identified several cost leaders in the same industry and this confirms our own experience. Cost leadership, unless demonstrated by a lowest-price strategy, is relatively invisible and therefore cannot be used to win customers and gain competitive advantage. Indeed, it must be questioned whether or not cost leadership is a separate strategy. Sharp' suggests that 'having a cost advantage is merely a facilitator to differentiate, usually on price', adding that a low-cost firm seeks to remove bases for differentiation, so as to offer a generic product to the whole market, so reducing differences between segments. We would agree, to the extent that the nearer a competitive arena moves rewards a commodity market, the more likely it is that firms will use price as the primary competitive weapon. This will tend to happen as the market matures and will often result in a shakeout of supplying firms. A low-price strategy, often based on low process technology costs, can be used to gain market entry and market share, as some Japanese companies have demonstrated. Once established, such entrants can use market penetration to extend ranges and compete by upward differentiation while maintaining cost advantage. On the other hand, cost leadership built on technological advantage can be challenged, as even the Japanese are beginning to discover in the European car industry. Rather similarly, cost advantage built on experience-curve effects can be eroded by imitation and technology gains, as well as in other ways. More generally, cost escalation relative to competitors can narrow the advantage and render the firm vulnerable. In summary, we would argue that cost leadership can be a precarious strategy which may accelerate the move towards a commodity market in which, ultimately, no-one. benefits. Porter's alternative generic strategy is differentiation and this is more visibly customer-focused and value-orientated. If differentiation and its cost base are both managed well, competitive advantage can result. Porter argues that a differentiator should add attributes that are valued by the customer--the value of the product' being defined by the price that the customer is willing to pay. The primary aim is to maximise the profit gap between price (or income) and cost. Strong differentiation such as branding can be costly and may often need to be built over time. It is also true that a successful differentiator can choose' to take additional income in increased volumes, rather than increased prices. A misconception in regard to this strategic position is that a successful differentiator operates in high-price markets. In some circumstances, a strong price can be a positive differentiator, as customers correlate price with value. Certainly Lamborghini is a successful high-price differentiator; Morgan Cars is also a successful differentiator, but operates in a narrow niche at a price which is not high by many criteria. Differentiation strategies also have their risks. Strong differentiation can be costly; buyers may be deterred by rising selling prices and desert to lower-cost competitors, sacrificing some of the features or attributes. Indeed, buyers' needs for highly differentiated products can wane over time, a trend accelerated by imitators narrowing the differentiation gap. A differentiator cannot afford to be complacent. Porter states that a firm should be specific in its choice of competitive strategy. If it is not, he argues, it runs the risk of being 'stuck in the middle'. Miller,[5] however, argues that a sharply specialised strategy can be disastrous: 'most products must satisfy a significant market in numerous ways: with quality, reliability, style, novelty, convenience, service and price. Unless all of the important hurdles are met, customers will be driven away'. So whether 'stuck in the middle' is necessarily so disastrous is debatable. All products must possess core attributes which will be offered by all competitors in a given market and without which they would not be saleable in that market. Even in commodity markets, firms will attempt to differentiate, primarily through intangible attributes such as customer service or branding. So most firms will try to lift their product offering above the lowest common denominator. They will do this with varying degrees of success and with varying cost bases, none of them holding the least cost position. We would argue that there is no essential need to distinguish between lowest-cost and differentiation positions. it can be possible to be both 'better and cheaper', as the Japanese have shown us. Pearson[6] illustrates the three competitive positions (Figure 2). We would suggest that, rather than there being three discrete positions, there is actually a continuum of cost/price/ profit positions with successful firms achieving sufficient differentiation sufficiently cost effectively to guarantee superior profits. Miller, arguing along similar lines, suggests that a mixed strategy, combining some aspects of differentiation with cost-effectiveness, has advantages. It avoids, he claims, the risk of over-specialisation while allowing the firm to benefit from multiple abilities and the synergies between them. Successful differentiators can increase market share and so achieve cost advantage from scale economies and experience curve effects. Going back to the generic strategies matrix (Figure 1), it can be seen that Porter offers two further strategic dimensions based on the definition of the target market. As Faulkner and Bowman[4] point out, cost leadership and differentiation are about how to compete, while focus is about where to compete. Under our suggested approach, by testing the five forces model at various magnifications of the competitive arena,[7] the ground is prepared for a more specific focus decision. We believe that this is important, because the alternative is that the firm could be driven towards a particular level of focus without insisting that the alternatives are examined systematically. However, it must be questioned whether the lowest-cost competitor has any place bidding for a narrow target market. As Sharp[3] suggests, such a competitor should aim for the total market, seeking to exploit every segment where cost advantage can be useful. Consequently, we would argue that focus strategies are for differentiators, who can seek to offer a uniquely desirable product separately to each targeted segment. There are, though, as Porter identified, problems for focused differentiators: the attributes required by the narrow target may move closer to those required by the wider market; competitors can sub-segment the focus market; low-cost producers offering less differentiated products can enter the market; Attempts to serve two or more focus segments can cause confusion in the supplier firm, possibly in the marketplace as well. However, focus strategies can offer superior profits to those firms that cater well for the demands of a specific segment. The higher costs of sector-specific differentiation can be offset by the economies of simpler promotion and distribution, for example. Porter's value chain[8] offers a useful vehicle for analysing and developing differentiation strategies cost effectively. We shall discuss this next month. 1. PORTER, M.E.: Competitive Strategy: Techniques for analysing industries and competitors. Free Press, 1980. 2. PARTRIDGE, M.J. and PERREN, L.J.: 'Achieving competitive advantage', Management Accounting, Vol 71, No 10, November 1993. 3. SHARP, B.: 'Competitive marketing strategy: Porter revisited', Marketing Intelligence and Planning, Vol 9, No 1, 1991. 4. FAULKNER, D. and BOWMAN, C.: 'Generic strategies and congruent organisational structures: some suggestions', European Management Journal, Vol 10, No 4, December 1992. 5. MULLER, n.: 'The generic strategies trap', The Journal of Business Strategy, Jan/Feb 1992. 6. PERSON, G.: Strategic Thinking. Prentice Hall, 1990. 7. PARTRIDGE, M.J. and PERREN, L.J.: 'Defining the competitive arena: a flexible and innovation driven approach', Management Accounting, Vol 72, No 4, April 1994. 8. PORTER, M.E.: Competitive Advantage: Creating and sustaining superior performance. Free Press, 1985. CHART: Figure 1: The generic strategies matrix DIAGRAM: Figure 2: Alternative competitive positions