C4D in Malaria Programming, UNICEF, 2010

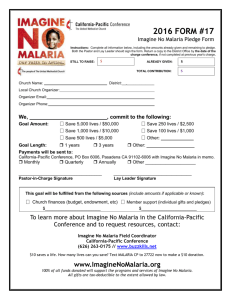

advertisement