Parts I & II

advertisement

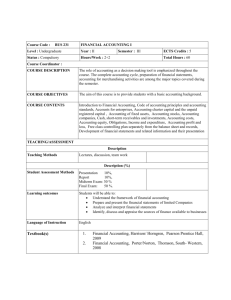

Economic & Financial Data Analysis II This subject consists of two parts. • Part I (Lecturer: Tin Nguyen) Basic elements of probability & statistics. Fundamentals of regression analysis. Part II (Lecturer: Eran Binenbaum) Topics to be given later. EFDA II Main & Other Textbooks • Main textbook (for both parts) – Analysis of Economic Data by (Wiley) • Other textbooks – Introduction to Econometrics by Stock & Watson (Ch. 1-5 & 12) – Essential of Econometrics by Gujarati (Ch. 1-7) – Using Econometrics by Studenmund (Ch. 1-6 & 11) EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 2 Lectures • Lectures – focus on the key topics – explain difficult topics from textbook – show worked examples – provide extra materials not in textbook. • Lecture Notes – Detailed notes. – Copies of lectures are downloadable from MyUni EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 3 Assessment • Exam 3 hours 70% • Tutorial (both parts) 10% • Tests (Parts I & II) 20% EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 4 Tutorials (10%) • One mark will be given for each tutorial attended and satisfactorily participated, up to a maximum of 10 marks (i.e. each student can receive a full 10 marks for tutorials with one absent). One mark will also be given for each absence if a justifiable reason can be given with adequate evidence, e.g. a medical certificate. EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 5 Objective of Part 1 • The objective of part 1 of this subject is to help you to acquire an elementary background in probability theory and statistics necessary for the proper understanding of econometric tests and problems and fundamentals of regression analysis. EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 6 Real-world Questions • Some real world questions may appear to require a YES or NO answer, e.g. – Are women being discriminated against in pay? – Are people with a university degree more likely to be employed and earn more than those without a degree? • However, on closer scrutiny, we often want numerical answers to such questions, e.g. – How much more likely a person with a degree will find employment than a person without such a degree, other things being equal. – How much a woman earns less than a man, other things being equal (i.e. all other individual EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 characteristics – age, education, experience,..,7 - Choice of Topics • Here, the focus will be on estimation procedures and tests that are commonly used in practice. Fore example, apart from ordinary least squares (OLS) regression, we may have to deal with: – Instrumental variable regression, which arises when the residual is expected to be correlated with a stochastic regressor. A valid instrument is assumed to be exogenous (uncorrelated with the residual) and correlated reasonably well with the variable it is used to represent. EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 8 Distinct Features of EFDA II • To ensure that the tools learning in EFDA II are of practical value to real life research, the following three distinct features are adopted. – Large sample approach. • This involves the use of large-sample approximations to sampling distributions for hypothesis testing and confidence intervals. • Note that small sample t-distribution or Fdistribution requires the assumption that the residual has a normal distribution, an assumption which does not often hold in practice. EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 9 Three Distinct Features of EFDA II – Stochastic regressors. Regressors are assumed to be random rather than to be fixed in repeated sampling. – Heteroscedasticity. Heteroscedastic errors are generally assumed. Heteroscedasticity-robust standard errors will be used to eliminate worries about whether EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 is present or not (i.e. there heteroscedasticity 10 Contemporary Choice of Topics It is useful to discuss briefly here some important topics which are covered in the textbook but are not included in EFDA II. EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 11 Instrumental variables regression • Instrumental variables regression is presented as a general method for handling correlation between the error term and a regressor, (which can arise for many reasons, including simultaneous causality). • The two assumptions for a valid instrument are: exogeneity and relevance. EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 12 Program Evaluation • An increasing number of econometric studies analyse either randomised controlled experiments or quasi-experiments, also known as natural experiments. • This research strategy can be presented as an alternative approach to the problems of • omitted variables & • simultaneous causality EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 13 Forecasting • Forecasting topic considers univariate (autoregressive) and multivariate forecasts using time series regression, not large simultaneous equation structural models. • This topic also features a practically oriented treatment of stochastic trends • unit root tests, • tests for structural breaks & • pseudo out-of-sample forecasting all in the context of developing stable and reliable time series fore casting models. EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 14 Skilled Producers & Sophisticated Consumers of Empirical Results • It is hoped that students using this book will become skilled producers and sophisticated critical users of empirical results. • To do so, they must learn not only how to use the tools of regression analysis, but also how to assess the validity of empirical analyses presented to them. EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 15 Threats to Internal & External Validity After learning the main tools of regression analysis, the threats to internal and external validity of an empirical study should be considered: data problems & issues of generalizing findings to other settings main threats to regression analysis, including: o o o o omitted variables, functional form misspecification, errors-in-variables, and simultaneity. EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 16 TOPIC 1: Economic Questions and Data • Many important real-world questions demand specific numerical answers, e.g. Do smaller elementary school class sizes produce higher test scores? What is the price elasticity of the demand for cigarettes? What is the private returns to an additional year of education? • The aim is to show you how you can learn from data but at the same time be self-critical and aware of the limitations of empirical analyses. EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 17 A special message for those intended to carry out research for a dissertation for: B.Ec. (Honours) in Economics Master of Applied Economics Master of Economics Ph.D. in Economics Choose a thesis topic in which there is sufficient scope and data for applying the analytical and econometric or statistical tools you have learned from your econometric and economic theory subjects at levels II and III or higher, e.g. EFDAII, Applied Econometrics III, Micro II, Macro II, Economic Theory III, etc. EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 18 Economic Questions 1.1 Economic Questions • Many decisions in economics, business, and government hinge on understanding relationships among variables in the world around us. These decisions require quantitative answers to quantitative questions. The following four of these questions concern education policy, racial bias in mortgage lending, cigarette consumption, and macroeconomic forecasting. EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 19 Question 1: Does Reducing Class Size Improve Elementary School Education? One prominent proposal for improving basic learning is to reduce class sizes at elementary schools. With fewer students in the classroom, the argument goes, each student gets more of the teacher's attention, there are fewer class disruptions, learning is enhanced, and grades improve. For practical reasons, we also have to ask the following questions. EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 20 But what is the effect on elementary school education of reducing class size? Reducing class size costs money (It requires hiring more teachers and, if the school is already at capacity, building more classrooms.) To weigh costs and benefits, however, the decision maker must have a precise quantitative understanding of the likely benefits. EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 21 Is the beneficial effect on basic learning of smaller classes large or small? Is it possible that smaller class size actually has no effect on basic learning? • Common sense cannot provide a quantitative answer to the question of what exactly is the effect on basic learning of reducing class size. • To provide such an answer, we must examine empirical evidence, that is, evidence based on data-relating class size to basic learning in elementary schools. EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 22 The Benefits-Costs of Class Size: An Example • As an example, let us examine the relationship between class size and basic learning using data gathered from 420 California school districts in 1998. • In the California data, students in districts with small class sizes tend to perform better on standardised tests than students in districts with larger classes. • While this fact is consistent with the idea that smaller classes produce better test scores, it might simply reflect many other advantages that students in districts with small classes have over their counterparts in districts with large classes. EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 23 The Benefits-Costs of Class Size: An Example (cont.) • For example, districts with small class sizes tend to have wealthier residents than districts with large classes, so students, in small-class districts could have more opportunities for learning outside the classroom. It could be these extra learning opportunities that lead to higher test scores, not smaller class sizes. • We can use multiple regression analysis to isolate the effect of changes in class size from changes in other factors, such as the economic background of the students. EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 24 Question 2: Is There Racial Discrimination in the Market for Home Loans? • By law, U.S. lending institutions cannot take race into account when deciding to grant or deny a request for a mortgage: applicants who are identical in all ways but their race should be equally likely to have their mortgage applications approved. In theory, then, there should be no racial bias in mortgage lending. • However, researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston found (using data from the early 1990s) that 28% of black applicants are denied mortgages, while only 9% of white applicants are denied. Do these data indicate that, in practice, there is racial bias in mortgage lending? If so, how large is it? EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 25 Is There Racial Discrimination in the Market for Home Loans? • The fact that more black than white applicants are denied in the Boston Fed data does not by itself provide evidence of discrimination by mortgage lenders, because the black and white applicants differ in many ways other than their race. • Before concluding that there is bias in the mortgage market, these data must be examined more closely to see if there is a difference in the probability of being denied for otherwise identical applicants and, if so, whether this difference is large or small. • To do this requires econometric methods that make it possible to quantify the effect of race on chance of obtaining a mortgage, holding constant other applicant characteristics, notably their ability to repay the loan. EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 26 Question 3: How Much Do Cigarette Taxes Reduce Smoking? • Cigarette smoking is a major public health concern worldwide. Many of the costs of smoking, such as the medical expenses of caring for those made sick by smoking and the less quantifiable costs to non-smokers who prefer not to breathe second-hand cigarette smoke, are borne by other members of society. • Because these costs are borne by people other than the smokers - there is a role for government intervention in reducing cigarette consumption. One of the most flexible tools for cutting consumption is to increase taxes on cigarettes. Basic economics says that if cigarette prices go up, consumption will go down. But by how EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 27 much? If the sales price goes up by 1%, by what percentage will the quantity of cigarettes sold decrease? • The percentage change in the quantity demanded resulting from a 1% increase in price is the price elasticity of demand. • If we want to reduce smoking by a certain amount, say 20%, by raising taxes, then we need to know the price elasticity to calculate the price increase necessary to achieve this reduction in consumption. EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 28 But what is the price elasticity of demand for cigarettes? • Although economic theory provides us with the concepts that help us answer this question, it does not tell us the numerical value of the price elasticity of demand. To learn the elasticity we must examine empirical evidence about the behaviour of smokers and potential smokers; in other words, we need to analyse data on cigarette consumption and prices. EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 29 Cigarette Taxes and Sales • The data we examine are cigarette sales, prices, taxes, and personal income for U.S. states in the 1980s and 1990s. • In these data, states with low taxes, and thus low cigarette prices, have high smoking rates, and states with high prices have low smoking rates. • However, the analysis of these data is complicated because causality runs both ways: low taxes lead to high demand, but if there are many smokers in the state then local politicians might try to keep cigarette taxes low to satisfy their smoking constituents. • Methods for handling this "simultaneous causality", not covered in this course, should be used to estimate the priceEFDA elasticity of cigarette demand. II, Semester 2, 2004 30 Question 4: What Will the Rate of Inflation Be Next Year? It seems that people always want a sneak preview of the future. What will sales be next year at a firm considering investing in new equipment? Will the stock market go up next month and, if so, by how much? Will city tax receipts next year cover planned expenditures on city services? EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 31 Inflation Forecasting • One aspect of the future in which macroeconomists and financial economists are particularly interested is the rate of overall price inflation during the next year. • Professional economists (who require on precise numerical forecasts) use econometric models to make those forecasts. • A forecaster's job is to predict the future using the past, and econometricians do this by using economic theory and statistical techniques to quantify relationships in historical data. EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 32 Inflation Forecasting: Model • The data we use to forecast inflation are the rates of inflation and unemployment in the United States. • An important empirical relationship in macroeconomic data is the "Phillips curve," in which a currently low value of the unemployment rate is associated with an increase in the rate of inflation over the next year. EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 33 Quantitative Questions & Quantitative Answers • Each of the above four questions requires a numerical answer. • Economic theory provides clues about that answer-cigarette consumption ought to go down when the price goes up-but the actual value of the number must be learned empirically, that is, by analysing data. • Because we use data to answer quantitative questions, our answers always have some uncertainty: a different set of data would produce a different numerical answer. EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 34 Quantitative Questions & Quantitative Answers • Therefore, the conceptual framework for the analysis needs to provide both a numerical answer to the question and a measure of how precise the answer is. • The conceptual framework used in this book is the multiple regression model, the mainstay of econometrics. EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 35 The Role of Econometric Model • Economic model provides a mathematical way to quantify how a change in one variable affects another variable, holding other things constant, e.g. – What effect does a change in class size have on test scores, holding constant student characteristics (e.g. family income) that a school district administrator cannot control? – What effect does your race have on your chances of having a mortgage application granted, holding constant other factors such as your ability to repay the loan? EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 36 The Role of Econometric Model – What effect does a 1% increase in the price of cigarettes have on cigarette consumption, holding constant the income of smokers and potential smokers? • The multiple regression model and its extensions provide a framework for answering these questions using data and for quantifying the uncertainty associated with those answers. EFDA II, Semester 2, 2004 37