COPD - Go for the Gold - Case Western Reserve University

advertisement

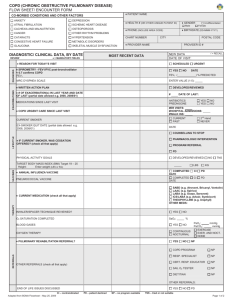

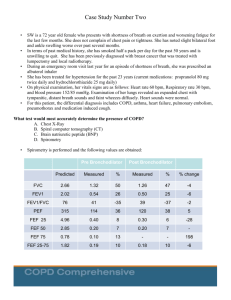

COPD - Go for the Gold Theresa Kearns, MBA, RN, NE-BC Director, HHVI System Ambulatory Cardiovascular Services Michelle Block, Esq. Assistant General Counsel Christy A. Cox BSN, RN Rodney J Folz, MD, PhD Chief, Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine Visiting Professor, Medicine – CWRU School of Medicine Quality Improvement Nurse Institute for Healthcare Quality & Innovation University Hospitals Case Medical Center Vincent Fazio Crystal Mosca, MD Clinical Application Analyst II Sharon Family Physicians Ambulatory EMR Physician Lead Rebecca Lovejoy Marianne Vest, MA, RN, CTTS Clinical Application Analyst II, EMR Ambulatory Senior Clinical Nurse Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation Harrington Heart & Vascular Institute Robin Rowell, MSN, RN, CNP Todd Zeiger, MD VP, UH Primary Care Institute Vice President, Harrington Heart & Vascular Institute Associate Chief Nursing Officer for Licensed Independent Practitioners Disclosures • Speakers in this presentation have no disclosures. Objectives • Introduce new UH COPD CareGuide and template note in AEMR. • Review interpretation of spirometry results and flow volume curves • • • Tobacco use/cessation • • • • Understand specific criteria for diagnosis and classification of COPD using spirometry Determination of a quality test Importance of assessing tobacco use history at every encounter Discuss how to motivate patients to quit and methods of treating those motivated to quit Recognize available UH resources for smoking cessation Vaccination • • Review new guidelines on Pneumococcal Vaccination and high risk indications for use under 65 Review Influenza Vaccination Protocols and discuss cost effectiveness of high dose COPD CareGuide Crystal Mosca, MD Sharon Family Physicians Ambulatory EMR Physician Lead High Reliability Medicine • Reliability = consistent excellence over long periods of time • Zero patient harm • Guidelines built into template How to Access • Choose diagnosis –COPD –Chronic Bronchitis –Emphysema –Click Recompile CAT SCORE • COPD Assessment Test • Patient completed quality of life assessment • Numerical score of respiratory health • Form will be embedded in EMR – will allow for data collection in the future Depression • 40% of COPD patients are affected by severe depressive symptoms • Screening with PHQ-2 is embedded into the HPI with option to pull in PHQ-9 • Prompts physicians to think about depression as a comorbidity and further screen or treat as needed Orderables • Orders –Diagnostic testing –Labs • Instructions/Patient Education • Rx • Follow-ups and Referrals screenshot Rx • Prescriptions are listed in order of priority of treatment in COPD • Under each category listed in order of preferred use by UH formulary and cost Examples • screenshot Spirometry Rodney J Folz, MD, PhD Chief, Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine Visiting Professor, Medicine – CWRU School of Medicine G lobal Initiative for Chronic O bstructive L ung D isease http://www.goldcopd.org Definition of COPD • COPD is a preventable and treatable disease with some significant extrapulmonary effects that may contribute to the severity in individual patients. • Its pulmonary component is characterized by airflow limitation that is not fully reversible. • The airflow limitation is usually progressive and associated with an abnormal inflammatory response of the lung to noxious particles or gases … 85% of the time due to tobacco smoke. MMWR 57:1221, 2008 Celebrities with COPD Johnny Carson Christy Turlington Amy Winehouse Dean Martin Leonard Nimoy Leonard Bernstein Loni Anderson Risk Factors for COPD Nutrition Infections Socio-economic status Genetics Aging Populations Diagnosis of COPD COPD Diagnostic Criteria • Clinical diagnosis suspected in any patient with: • • • • Dyspnea Chronic cough Sputum production History of exposure to risk factors for COPD. • Post bronchodilator FEV1/FVC < 0.70 Caveats • Characteristic symptoms are chronic and progressive. • dyspnea, cough, and sputum. • Cough and sputum may precede airflow limitations by many years. • Airflow limitations may develop without cough and sputum. Four ways to Assess COPD 1. Assessment of current symptoms 2. Assessment of severity of airflow limitation 3. Assessment of exacerbation risk 4. Assessment of presence of comorbidities 1. Assessment of Symptoms • Best way to assess symptoms is to use validated questionnaires: – Modified Medical Research Council dyspnea scale. MMRC – COPD Assessment Test CAT 2. Assessment of Airflow Limitation Severity Global Strategy for Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD (C) or > 1 leading to hospital admission (D) 3 2 (A) (B) 1 1 (not leading to hospital admission) 0 CAT < 10 CAT > 10 Symptoms mMRC > 2 mMRC 0–1 Breathlessness © 2015 Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (Exacerbation history) ≥2 4 Risk (GOLD Classification of Airflow Limitation) Risk Combined Assessment of COPD Global Strategy for Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD Manage Stable COPD: Pharmacologic Therapy RECOMMENDED FIRST CHOICE ICS + LABA or LAMA GOLD 3 GOLD 2 GOLD 1 D 2 or more or > 1 leading to hospital admission ICS + LABA and/or LAMA A B SAMA prn or SABA prn LABA or LAMA 1 (not leading to hospital admission) 0 CAT < 10 mMRC 0-1 CAT > 10 mMRC > 2 © 2015 Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Exacerbations per year GOLD 4 C Spirometry in Primary Care Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2010 Spirometry - Introduction • Spirometry is the gold standard for COPD diagnosis • Underuse leads to inaccurate COPD diagnosis • Widespread uptake has been limited by: – Concerns over technical performance of operators – Difficulty with interpretation of results – Lack of approved local training courses – Lack of evidence showing clear benefit when spirometry is incorporated into management What is Spirometry? Spirometry is a method of assessing lung function by measuring the total volume of air the patient can expel from the lungs after a maximal inhalation. Why Perform Spirometry? • Measure airflow obstruction to help make a definitive diagnosis of COPD • Confirm presence of airway obstruction • Assess severity of airflow obstruction in COPD • Detect airflow obstruction in smokers who may have few or no symptoms • Monitor disease progression in COPD • Assess one aspect of response to therapy • Assess prognosis (FEV1) in COPD • Perform pre-operative assessment Desktop Electronic Spirometers Small Hand-held Spirometers Standard Spirometric Indicies • FEV1 - Forced expiratory volume in one second: The volume of air expired in the first second the blow • FVC - Forced vital capacity: The total volume of air that can be forcibly exhaled breath • FEV1/FVC ratio: The fraction of air exhaled in the first second relative to the total volume exhaled Predicted Normal Values Affected by: Age Height Sex Ethnic Origin Criteria for Normal Post-bronchodilator Spirometry • FEV1: % predicted > 80% • FVC: % predicted > 80% • FEV1/FVC: > 0.7 - 0.8 (depending on age) Normal Trace Showing FEV1 and FVC FVC Volume, liters 5 4 FEV1 = 4L 3 FVC = 5L 2 FEV1/FVC = 0.8 1 1 2 3 4 Time, sec 5 6 SPIROMETRY OBSTRUCTIVE DISEASE Spirometry: Obstructive Disease Normal Volume, liters 5 4 3 FEV1 = 1.8L 2 FVC = 3.2L 1 FEV1/FVC = 0.56 1 2 3 4 5 Time, seconds 6 Obstructive Spirometric Diagnosis of COPD • COPD is confirmed by post– bronchodilator FEV1/FVC < 0.7 • Post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC measured 15 minutes after 400µg salbutamol or equivalent Bronchodilator Reversibility Testing • Provides the best achievable FEV1 (and FVC) • Helps to differentiate COPD from asthma Must be interpreted with clinical history - neither asthma nor COPD are diagnosed on spirometry alone SPIROMETRY RESTRICTIVE DISEASE Criteria: Restrictive Disease • FEV1: normal or mildly reduced • FVC: < 80% predicted • FEV1/FVC: > 0.7 Spirometry: Restrictive Disease Normal Volume, liters 5 4 3 Restrictive 2 FEV1 = 1.9L FVC = 2.0L 1 FEV1/FVC = 0.95 1 2 3 4 5 Time, seconds 6 SPIROMETRY Flow Volume Flow Volume Curve • Standard on most desk-top spirometers • Adds more information than volume time curve • Less understood but not too difficult to interpret • Better at demonstrating mild airflow obstruction Flow Volume Curve Expiratory flow rate Maximum expiratory flow (PEF) L/sec TLC FVC Inspiratory flow rate L/sec Volume (L) RV Flow Volume Curve Patterns Obstructive and Restrictive Severe obstructive Volume (L) Reduced peak flow, scooped out mid-curve Restrictive Expiratory flow rate Expiratory flow rate Expiratory flow rate Obstructive Volume (L) Steeple pattern, reduced peak flow, rapid fall off Volume (L) Normal shape, normal peak flow, reduced volume PRACTICAL SESSION Performing Spirometry Spirometry Training • Training is essential for operators to learn correct performance and interpretation of results • Training for competent performance of spirometry requires a minimum of 3 hours • Acquiring good spirometry performance and interpretation skills requires practice, evaluation, and review • Spirometry performance (who, when and where) should be adapted to local needs and resources • Training for spirometry should be evaluated Obtaining Predicted Values • Independent of the type of spirometer • Choose values that best represent the tested population • Check for appropriateness if built into the spirometer Optimally, subjects should rest 10 minutes before performing spirometry Withholding Medications Before performing spirometry, withhold: Short acting β2-agonists for 6 hours Long acting β2-agonists for 12 hours Ipratropium for 6 hours Tiotropium for 24 hours Optimally, subjects should avoid caffeine and cigarette smoking for 30 minutes before performing spirometry Volume, liters Reproducibility - Quality of Results Time, seconds Three times FVC within 5% or 0.15 litre (150 ml) Spirometry - Quality Control • Most common cause of inconsistent readings is poor patient technique Sub-optimal inspiration Sub-maximal expiratory effort Delay in forced expiration Shortened expiratory time Air leak around the mouthpiece • Subjects must be observed and encouraged throughout the procedure Equipment Maintenance • Most spirometers need regular calibration to check accuracy • Calibration is normally performed with a 3 litre syringe • Some electronic spirometers do not require daily/weekly calibration • Good equipment cleanliness and anti-infection control are important; check instruction manual • Spirometers should be regularly serviced; check manufacturer’s recommendations Troubleshooting Examples - Unacceptable Traces Unacceptable Trace – Stop Early Volume, liters Normal Time, seconds Unacceptable Trace - Coughing Volume, liters Normal Time, seconds Some Spirometry Resources • Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) - www.goldcopd.org • Spirometry in Practice - www.brit-thoracic.org.uk • ATS-ERS Taskforce: Standardization of Spirometry. ERJ 2005;29:319-338 www.thoracic.org/sections/publications/statements • National Asthma Council: Spirometry Handbook www.nationalasthma.org.au Immunization Update for the COPD patient Todd Zeiger, MD Vice President, University Hospitals Primary Care Institute Purpose of review • Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. • Most acute exacerbations are triggered by communityacquired respiratory infections. • Medications to treat COPD exacerbations are limited; therefore, identifying and executing effective ways to prevent exacerbations are needed. • Influenza and pneumococcal vaccines are currently recommended for all persons with COPD. However, current immunization rates are low Vaccination of the COPD patient • Tdap vaccine to protect against whooping cough and tetanus • Influenza vaccine each year to protect against seasonal flu • Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine to protect against pneumonia and other pneumococcal disease Influenza Vaccination: How well does it work? • Flu vaccination also has been shown to be associated with reduced hospitalizations among people with diabetes (79%) and chronic lung disease (52%). • A study that looked at flu vaccine effectiveness over the course of three flu seasons estimated that flu vaccination lowered the risk of hospitalizations by 61% in people 50 years of age and older. 2015-2016 Influenza Vaccine Preparations • Intramuscular (IM) vaccines will be available in both trivalent and quadrivalent formulations. • High dose vaccines(IM) will all be trivalent this season • For people who are 18 through 64 years old, a jet injector can be used for delivery of one particular trivalent flu vaccine (AFLURIA® by bioCSL Inc.). • Nasal spray vaccines will all be quadrivalent this season. • Intradermal vaccine will all be quadrivalent 2015-2016 Influenza Vaccine • Contains the following 4 viral strains for 2015/2016 northern hemisphere season – A/California/7/2009 (H1N1) pdm09-like virus (same strain as was used for 2009 H1N1 monovalent vaccines) – A/Switzerland/9715293/2013 (H3N2)-like virus (new strain for 2015/2016) – B/Phuket/3073/2013-like virus (B/Yamagata lineage) (new strain for 2015/2016) – B/Brisbane/60/2008-like virus (B/Victoria lineage vaccine virus) Who Should Receive Influenza Vaccine? EVERYONE Who Should Not Receive Influenza Vaccine? • Severe hypersensitivity (eg, anaphylaxis) to any component of the vaccine, including egg protein, or following a previous administration of any influenza vaccine • Persons with hives-only allergy to eggs, can receive the inactivated influenza vaccine • History of Guillain-Barre within 6 weeks of influenza vaccination High-Dose vs Standard-Dose • Increased Immunological response • ? Improved clinical efficacy • Recent data- high dose Fluvax may show increased clinical utility in Nursing home patients – to be presented Oct • A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine (08/2014) indicated that the high-dose vaccine was 24.2% more effective in preventing flu in adults 65 years of age and older relative to a standard-dose vaccine. The confidence interval for this result was 9.7% to 36.5%). Pneumococcal Vaccination: PPSV23 Vaccine • Vaccine strains account for 88% of bacteremic pneumococcal disease • 75% efficacy against invasive disease • 30% efficacy against pneumonia • Duration of immunity at least 6 years File TM, et al. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2012; 20:3-9 Adult PPSV23 Vaccine Recommendations • All Adults 65 years of age and older • Adults 19-64 (immunocompetent) • Chronic illness (heart, lung, liver, diabetes, alcoholism, CSF leaks, cochlear implants) • Asthma • Cigarette smoking Pneumococcal Vaccination: PCV13 • CAPiTA trial • demonstrated 45.6% efficacy of PCV13 against vaccine-type pneumococcal pneumonia • 45.0% efficacy against vaccine-type nonbacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia • 75.0% efficacy against vaccine-type IPD among adults aged ≥65 years PCV13 Vaccine in Adults • Pneumococcal (PPSV23) vaccine naïve subjects: • An evaluation of immune response after a second pneumococcal vaccination administered 1 year after the initial study doses showed that subjects who received PPSV23 as the initial study dose had lower antibody responses after subsequent administration of PCV13 than those who had received PCV13 as the initial dose followed by a dose of PPSV23, regardless of the level of the initial response to PPSV23 COPD: PCV13 and PPSV23 before age 65 Summary • Pneumococcal disease results in significant clinical and economic burden • Current vaccines are effective in preventing invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) • Despite proven efficacy and safety of vaccines, <20% of at-risk adults < 65 years of age are vaccinated Summary • Advances of vaccines often caused by refusals due to irrational beliefs • Responsible healthcare professionals must increase education of public and encourage usage • Practice what we preach • Be vaccine champions • “You are going to get your x shot today” Tobacco Cessation Marianne Vest, MA, RN, CTTS Senior Clinical Nurse Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation Harrington Heart & Vascular Institute Tobacco Dependence • Tobacco dependence is a chronic disease that often requires repeated intervention and multiple attempts to quit. • Effective treatments exist that can significantly increase rates of long-term abstinence. • However, first the question must be asked! Are you using any form of tobacco? Importance of Regularly Assessing Tobacco Use • Clinicians can make a difference with minimal intervention (<3 minutes) • Research has shown a relation between intensity of intervention and cessation outcome • Even if a patient is not ready to quit at that time, a brief intervention may enhance motivation & increase the likelihood of future quit attempts • The average number of quit attempts prior to being successful = SIX! Tobacco Cessation Counseling by physicians, nurses, and other clinicians all are of proven benefit. Estimated abstinence at 5+ months With help from a clinician, the odds of quitting approximately doubles. 30 n = 29 studies Compared to patients who receive no assistance from a clinician, patients who receive assistance are 1.7–2.2 * times as likely to quit successfully for 5 or more months. 20 2.2 1.7 10 1.0 1.1 0 No clinician Self-help material Nonphysician clinician Physician clinician * Odds ratios Type of Clinician Fiore et al. (2008). Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: USDHHS, PHS, May 2008. Team work is effective: Counseling by more than one clinician (e.g. physician and nurse) is better than either one alone! Estimated abstinence rate at 5+ months Compared to smokers who receive assistance from no clinicians, smokers who receive assistance from two or more types of clinicians are 2.4–2.5* times as likely to quit successfully for 5 or more months. 30 n = 37 studies 20 2.5 2.4 Two Three or more 1.8 10 1.0 0 None One Number of Clinician Types Number of Clinician Types * Odds ratios Fiore et al. (2008). Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: USDHHS, PHS, May 2008. TOBACCO DEPENDENCE: A 2-PART PROBLEM Tobacco Dependence Physiological The addiction to nicotine Treatment Medications for cessation Behavioral The habit of using tobacco Treatment Behavior change program Treatment should address the physiological and the behavioral aspects of dependence. Behavioral Change: The Spirit of Motivational Interviewing • Partnership – Not confrontation • Acceptance – Not judgement • Compassion – Not indifference • Evocation – Not advice A meta-analysis of 14 randomized trials showed that compared to brief advice or usual care, MI increased 6-month cessation rates by about 30% Lai et al, Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010 Motivational Interviewing • Express empathy - use open ended questions to explore - use reflective listening to seek shared understanding • Develop discrepancy - between present behavior & expressed goals • Roll with resistance • Support self-efficacy -offer options for achievable small steps toward change Elicit-Provide- Elicit • Elicit: ask what the patient knows or would like to know (pharmacotherapy, relapse, etc) • Ask permission: ‘Do you mind if I share with you some of what we know?’ • Provide: information in a neutral, nonjudgemental fashion (‘research suggests that….) • Elicit: patient’s interpretation (‘what does this mean to you?’ ‘how can I help?’ ‘do you have any questions?’) Suggestions for Behavioral (habit) Change • Only smoke in one room of the home • Put cigs in trunk of car when driving • Change the routine: coffee in the AM • Put cigs in basement/not normal room • Change cigarette brands • Use a straw or toothpick in mouth instead of cig Behavioral Change KEY POINTS • Position yourself as the beginning of the process, not the provider of the entire cessation program • You want the patient to talk themselves into changing rather than you telling them they have to change! • Offer treatment “Quitting smoking can be hard, but there is good treatment available and I can help. Would you like to try?” Pharmacologic Methods: First-line therapies Three general classes of FDA-approved drugs for tobacco cessation: • Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) Nicotine patch, gum, lozenge, nasal spray, inhaler • Psychotropics Sustained-release bupropion administered twice daily • Partial nicotinic receptor agonist Varenicline **E-cigarettes and related products are NOT currently FDA approved for tobacco cessation. Long-term (6 month) Quit Rates for Available Cessation Medications 30 Active drug Placebo 25 23.9 20.2 Percent quit 20 19.0 18.0 17.1 16.1 15.8 15 11.8 11.3 10.3 10 11.2 9.1 9.9 8.1 Nicotine patch Nicotine lozenge 5 0 Nicotine gum Nicotine nasal spray Nicotine inhaler Bupropion Varenicline Data adapted from Cahill et al. (2008). Cochrane Database Syst Rev; Stead et al. (2008). Cochrane Database Syst Rev; Hughes et al. (2007). Cochrane Database Syst Rev Combination Pharmacotherapy • Combination NRT Long-acting formulation (patch) • Produces relatively constant levels of nicotine PLUS Short-acting formulation (gum, lozenge) • Allows for acute dose titration as needed for nicotine withdrawal symptoms • Bupropion SR + NRT Relative Efficacy/Safety of Tobacco Dependence Pharmacotherapy • Varenicline is superior to NRT monotherapy or Bupropion • NRT monotherapy & Bupropion are of about equal efficacy • Combination NRT may be as efficacious as Varenicline UH Resources • Harrington Heart & Vascular Institute -experienced Certified Tobacco Treatment Specialists -referral for patients who have failed at least 1 recent trial of pharmacotherapy by primary or specialty physician -accessible via outpatient AEMR orders • Beat the Pack – employee program • Plan Q Mobile app – Pfizer • LMS Tobacco Cessation education online course -will go live 10/1/2015 AEMR Order COPD System Steering Committee Theresa Kearns, MBA, RN, NE-BC Director, HHVI System Ambulatory Cardiovascular Services COPD System Steering Committee • Reduce readmission rate of the PNA and COPD patient population • Institute best practices from literature review • Collaborate with pharmaceutical company to enhance medication accessibility for COPD patients • Develop innovative interventions and sustainable outcomes to decrease LOS and prevent readmissions • Prevent CMS penalties • Representation from all system hospitals Readmission Reduction Program Definition • 30-day unplanned readmission to any U.S. hospital • Populations: AMI, CHF, PN, COPD, Elective Hip/Knee Replacement • Includes Traditional Medicare only • Includes ages 65 and older only • Excludes transfers to another short-term general hospital • Excludes critical access hospitals (Conneaut & Geneva) • Risk-adjusted by secondary conditions, demographics, and procedures • Your hospital’s results are compared to similar hospitals (severity) Readmissions Reduction Program – COPD Discharges July-2011 to June-2014. Medicare FY 2016 Eligible Discharges Number of 30-Day Readmits Observed Adjusted Rate Expected Readmission Rate Readmission Ratio (>1.0 = higher than expected) National Observed Rate Ahuja 217 40 18.7% 18.8% 0.9923 20.2% Case 239 56 22.2% 21.3% 1.0428 20.2% Elyria 813 191 22.5% 20.0% 1.1224 20.2% Geauga 262 56 22.0% 22.4% 0.9792 20.2% Parma 748 171 22.6% 22.0% 1.0271 20.2% Regional 260 61 21.8% 20.6% 1.0616 20.2% Portage 259 50 18.8% 18.5% 1.0176 20.2% St. John 486 108 21.9% 21.5% 1.0187 20.2% Hospital FY 2015 was the 1st year for the program Patient Type EMERGENCY UH System COPD Volumes Facility UH Case Medical Center UH Regional Hospitals Bedford Campus UH Conneaut Medical Center UH Geauga Medical Center UH Geneva Medical Center UH Regional Hospitals Richmond Campus UH Ahuja Medical Center UH Parma Medical Center UH Elyria Medical Center Total Cases 233 125 138 74 181 129 192 166 405 1,643 Facility UH Case Medical Center UH Regional Hospitals Bedford Campus UH Conneaut Medical Center UH Geauga Medical Center UH Geneva Medical Center UH Regional Hospitals Richmond Campus UH Ahuja Medical Center UH Parma Medical Center UH Elyria Medical Center Total Cases 396 118 22 211 63 139 149 394 622 2,114 Facility UH Case Medical Center UH Regional Hospitals Bedford Campus UH Conneaut Medical Center UH Geauga Medical Center UH Geneva Medical Center UH Regional Hospitals Richmond Campus UH Ahuja Medical Center UH Parma Medical Center UH Elyria Medical Center Total Cases 92 13 20 16 11 65 38 47 136 438 Total Patient Type Jul-2014 to Jun-2015 INPATIENT ADMITS THRU THE ED Total Patient Type OBSERVATION Total Source: Premier. Principal Diagnosis of COPD Current Work • Tobacco Cessation • Home Care Pilot • e-vouchers • Monthly chart review by Dr. Schilz • RN Discharge Clinic • PFT ordering focus Best Practice: Tobacco Cessation Process Goal: System standardization and education for tobacco cessation process • Standardized resource pamphlet(s) • Utilize unbranded education resources • Coding/reimbursement education to capture lost revenue – LMS Educational video available 10/2015 • Pilot UHCMC inpatient initiation of tobacco cessation consult for COPD patients – Train additional educators COPD Admissions - % Active Tobacco Use Jul-2014 to Jun-2015 Patient Type Facility INPATIENT UH UH UH UH UH UH UH UH UH Total Active Tobacco Cases Case Medical Center Regional Hospitals Bedford Campus Conneaut Medical Center Geauga Medical Center Geneva Medical Center Regional Hospitals Richmond Campus Ahuja Medical Center Parma Medical Center Elyria Medical Center 190 51 9 89 38 50 58 118 221 824 Source: Premier. Principal Diagnosis of COPD Total Admissions 486 156 26 253 103 169 204 488 664 2,549 % Active Tobacco Users 39% 33% 35% 35% 37% 30% 28% 24% 33% 32% UHCMC Home Care Services PNA & COPD Pilot Goals • Enhance the quality of care for patients diagnosed with PNA and/or COPD • Reduce readmissions Patient Eligibility • Patient w/o insurance for home care or ineligible for traditional homecare • PNA admit/diagnosis during hospitalization with or w/o COPD • COPD exacerbation/diagnosis during admit with/without PNA • If patient declines home care visit, referral to RN DC clinic for a one time visit with same program goals as pilot. Funding • Home care visit funded by UHCMC, billed at $145/visit. Medication Management Spiriva eVoucher Program -- 5/2015 • Give eVoucher to COPD patients with order for Spiriva for a free 30 day supply of medication • Involve key leads from across UH to roll out to other facilities – Parma and Geneva • Review/explore additional pharmaceutical opportunities Chart Review Summary COPD Readmissions to UHCMC April 2014 – May 2015 • 80% of our COPD Admissions Represent African American Patients • Readmissions are evenly spread through the 30 days following discharge (28% in first week) • 42% of our COPD readmit events represent multiple (2-6) readmits from only 16 patients, 14 of 16 only admitted for COPD • Initial MICU admission does not seem to be an indicator of future readmission either to MICU or to UHCMC • COPD represents the major reason for 30 day readmission (57%) • CHF is the second leading reason for 30 day readmission (17%) Suggested Action Items • Continue data review – consider initial coding review • Understand population demographic • Focus initially on 16 patients • Focus on CHF management in complex patients, may independently look at this population • Suggest pulmonary consult for: – All readmits with primary readmit diagnosis of COPD – All GOLD III and IV patients (this will include oxygen dependent patients) – All MICU patients with COPD as admitting diagnosis to MICU (although there is some evidence that this is already done on both code white and current patients) Best Practices: Patient ‘touch’ moments • Respiratory Therapist: ˉ Educate patients during treatments on tobacco cessation ˉ Utilize Skylight video as reinforce healthy living ˉ Leverage order sets for EMR - PNA and COPD ˉ Appropriate dx and treatment • Pharmacy ˉ Investigate opportunities to partner with retail pharmacy (Giant Eagle) • Home Care ˉ Educate Care Coordinators regarding home care services pilot enrollment criteria UH System COPD Findings (Jul-2014 to Jun-2015) • No statistically significant trends up or down in admissions • 1,643 emergency encounters / treat & release • 2,114 admissions through the emergency dept. • 17% of admissions are direct admits • 32% of admissions with active tobacco use (per coding) • 36.2% of admissions had a PFT in previous 5 years • 83% COPD admits are thru the ED