why and how to specialise in tourism: an agenda for

advertisement

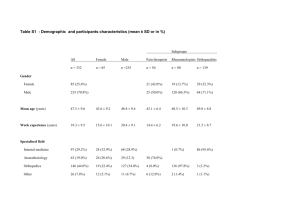

WHY AND HOW TO SPECIALISE IN TOURISM: AN AGENDA FOR JAMAICA Wolfgang Grassl “The Role of Government in Tourism – Enhancing Human and Economic Development” September 25-28, 2002 University of the West Indies Mona, Jamaica Preview 1. Introduction 2. Tourism Services and Economic Growth 3. Specialisation, Growth, and Country Size 4. Empirical Model Estimation 5. Policy and Strategy Implications for Jamaica 6. The Role of Government in Tourism 2 1. Introduction /1 specialisation vs. diversification W.A. Lewis: The Theory of Economic Growth (1955) “traditional” vs. “progressive” sectors smaller countries tend to be more specialised confronted with two facts about Caribbean: countries are, on average, very small countries increasingly specialise in tourism • lower productivity gains part of low-growth traditional sector 3 1. Introduction /2 worldwide empirical evidence: small states have comparatively higher GDP p.c. country size decreases monotonically with rising income levels predominant sector in small and fast-growing economies is service sector two stylised facts: specialisation in services (particularly in personal services) is compatible with fast growth fast-growing specialised countries tend to be small 4 1. Introduction /3 theoretical issue: Baumol’s “cost disease” comparatively lover productivity of services leads to rising price level answer: endogenous growth theory theses: tourism as an engine of growth for small countries country size effects benefit small countries • “Growth requires specialization, specialization requires co-ordination by a price mechanism, and this co-ordination is effective only in proportion to the response of individuals to changes in prices.” 5 2. Tourism Services and Econ. Growth /1 incongruity: higher-income countries tend to have larger service sectors personal services: • production = consumption • “embodied” in consumers (= tourists) assumption: admit only of little productivity growth does growth of service sector (particularly of tourism) crowd out higher-productivity sectors (agriculture and manufacturing)? can tourism maximise economic growth at all? 6 20 Top Countries 20 Bottom Countries Country size (population) Number of countries (Atlas method) Number of countries (PPP) Number of countries (Atlas method) Number of countries (PPP) < 50,000 50,000 - 1M 1M - 5M 5M - 10M 4 3 2 6 5 4 2 3 0 0 3 4 0 0 3 5 Total 15 14 7 8 Source: World Bank Share of countries by size in top 20 and bottom 20 countries by GNI per capita, 2000 Worldbank classification Countries Small countries (popul. < 3M) % of small countries Low income Lower middle income Upper middle income High income 63 54 38 52 11 21 18 26 17.5% 38.9% 47.4% 50.0% Total 207 76 36.7% Source: World Bank Share of small countries by World Bank income categories 7 2. Tourism Services and Econ. Growth /2 empirical evidence (first stylised fact): significant overlap of countries with strongest growth of GDP p.c. and countries with strongest share of tourism in GDP Caribbean countries with strongest tourism specialisation grow fastest allegedly negative impacts of specialisation: high leakages for imports sectoral displacement effects (“Dutch disease”) deleterious implications for culture and environment 8 100% 90% Tourism 80% 70% Agriculture 60% 50% Manufacturing 40% 30% 20% Services 10% 0% 1980 1985 1990 1995 Development of sectoral shares in GDP in the Caribbean (C-29) 2000 9 100% 90% 80% Tourism Agriculture 70% Manufacturing 60% 50% 40% 30% Services 20% 10% 19 80 19 81 19 82 19 83 19 84 19 85 19 86 19 87 19 88 19 89 19 90 19 91 19 92 19 93 19 94 19 95 19 96 19 97 19 98 19 99 20 00 20 01 0% Development of sectoral shares in GDP in Jamaica 10 3. Specialisation, Growth & Country Size/1 endogenous growth theory: growth driven by returns to increasing specialisation returns to increasing stock of human capital returns to knowledge accumulation by “learningby-doing” returns to knowledge accumulation by R&D and innovation growth due to increasing specialisation economic conditions in tourism-generating countries for tourism-receiving countries to warrant specialisation? 11 3. Specialisation, Growth & Country Size/2 pivot in explanation: terms-of-trade (TOT) under complete specialisation of all countries in either tourism or non-tourism goods, TOT: ( y N / y N ) ( y T / yT ) s p / p where s = elasticity of substitution consequently, y N / y N yT / yT 12 3. Specialisation, Growth & Country Size/3 what happens to TOT over time depends upon the extent to which non-tourism goods are substitutes for tourism if s > 1, TOT will be muted: specialisation in tourism harmful for growth if s < 1, specialisation not harmful for growth: TOT move fast enough to more than offset difference in sectoral productivity growth 13 3. Specialisation, Growth & Country Size/4 statistical evidence for OECD countries: s < 1 fulfilled countries with a higher degree of specialisation in tourism tend to have lower values for s • tourism services are characterised by a particularly low degree of substitutability for non-tourism goods • reasons: tourism goods are luxury goods (= take up less elastic shares in household budgets) offered in bundles and in a great variety of quality levels • resource-based tourism has particularly low s 14 3. Specialisation, Growth & Country Size/5 country size (second stylised fact): smaller countries have less intensive linkages but: smaller countries face lower opportunity costs of specialisation • issue: how to measure country size • absolute vs. relative (= resource-dependent) measures smaller countries tend to have larger amounts per capita of resources that attract tourists • larger relative resource endowment explains specialisation 15 3. Specialisation, Growth & Country Size/6 conclusions: as long as the elasticity of substitution in the consumer preferences of tourism-generating countries is low enough, two conditions will hold: countries with endowments of suitable resources large relative to the size of their labour force are likely to develop a comparative advantage in tourism these countries grow faster than those specialising in other sectors 16 4. Empirical Model Estimation /1 aggregate growth equation (Y / Y )t α 0 α1 ( y A / y A )t n α 2 ( y M / yM )t n α 3 ( y S / yS )t n α 4 ( yT / yT )t n ai = coefficients expressing contributions of sectors to aggregate growth of GDP n = time period over which independent variables are defined lagged by one year 17 4. Empirical Model Estimation /2 three data sets: C-29: 29 Caribbean countries (islands) • pooled cross-sectional aggregates • 1980-2000 (1986-1998 for H1) C-5: Barbados, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Jamaica, Trinidad Jamaica • 1980-2001 18 4. Empirical Model Estimation /3 hypotheses: H1: There is a significantly positive relationship between growth in tourism output and growth in real GDP. H2: There is no significantly negative relationship between growth in the share of services in real GDP and growth in the shares of agriculture and manufacturing, respectively, at higher levels of specialisation in services. H3: In small countries, the share of services in GDP will grow with country size. 19 4. Empirical Model Estimation /4 H1: supported H2: supported results somewhat less conclusive • no statistically significant displacement of agriculture or manufacturing by expansion of service sector • decline of agriculture correlates rather with slight increase in manufacturing and not in tourism • effect strongest for Haiti and Trinidad • at lower specialisation levels, crowding-out effects are stronger H3: supported 20 5. Policy & Strategy Implications for JA/1 Jamaica lacks comparative advantage in agriculture manufacturing competitive only in labourintensive and low-skill industries specialisation in export of services which services? ICT vs. tourism tourism specialisation: resource-based tourism low degree of substitutability product differentiation 21 5. Policy & Strategy Implications for JA/2 diversification a macro-strategy of larger countries specialisation a winning strategy for smaller countries Lewis: • “It is not true that the individual firm must be large in scale if there is to be efficiency or economic growth; but it is true that the advantages of specialization cannot be secured unless the economies of scale are available either within the firm or within the framework of well organized markets. All the same, the degree to which the well organized market can substitute for the large firm varies very much from industry to industry.” compensation for lacking economies of scale at industry level cooperation 22 Role of Government in Tourism shift from concentration on demand-side to supply-side policies in small states, macroeconomic policy instruments very limited in scope trade protectionism forbids itself in open economies government policies: stimuli for private sector to invest in education, R&D, training, and marketing provision of public goods: safety, clean beaches, efficient roads and airports, etc. coordinate strategic repositioning of country 23