D.E.Sam_Leiva-City of Knowledge 06JUL2012

advertisement

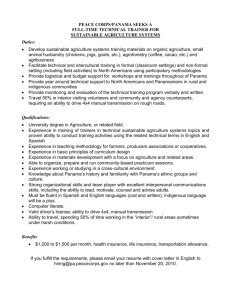

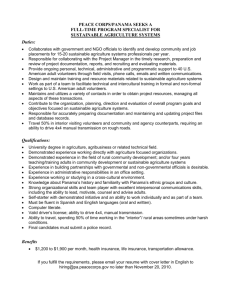

When Uncle Sam Says “Adios” What can the City of Knowledge teach us about incubators, BRAC, Creative Class Theory and Politics? D.E. “SAM” LEIVA david.leiva@eagles.usm.edu ABSTRACT The former site of Fort Clayton in Panama is home to the 296-acre technology cluster known as the "City of Knowledge.” Since 2000, it has operated under a private, nonprofit foundation with the emphasis on emerging technology companies growing to purportedly 185 tenants, including American universities, biotechnology firms and international nongovernmental organizations. In many respects, it has been considered a model for redevelopment of closed military bases leading to the question of how can the successes of the Panamanian base closure experience benefit future U.S. regions experiencing closures. A series of economic development approaches ranging from cluster theory to new growth theory to the creation of the creative class offer the framework for some explanation as to the Panamanian success. Nearly 129,000 civilian and defense jobs were lost in 73 different locations nationwide during the 1988, 1991, 1993, and 1995 Base Realignment and Closure Commission closures, but officials said nearly all of those jobs were replaced by the private sector. Federal officials contend that the redevelopment of base property is widely viewed as a key component of economic recovery for communities experiencing economic dislocation due to jobs lost from a base closure. The closure of a base makes buildings and land available for use that can generate new economic activity in the local community. But, few closures had such a question mark on the future of an entire nation as did the closure of all military bases in the country of Panama, where thousands of buildings and nearly 100,000 acres of land was left behind by the U.S. military under a 1977 treaty that returned the Panama Canal to Panama and withdrew U.S. troops at the turn of the century. At the time, the U.S. Southern Command estimated its presence in Panama contributed about $370 million a year to the economy, about 8 percent of the country's GDP. Naysayers said the Latin American country would crumble. Twelve years later, few can recall a time when the Latin American country was a laboratory for testing on nerve agents and depleted uranium. And while, many communities in the United States have seen similar relative successes, few have been able to do it outside the context of a strong national economy and the ultimate safety net provided by the federal government. Understanding base closures is important because it shifts the government's economic stimulus to the private sector, turning into a "complex nexus" of publicprivate negotiations and entities and the different means of calculating value: government's job creation versus the private sector's return on investment. But, not all that shines is gold. Officials from the City of Knowledge declined repeated requests for interviews, and it remains unclear whether the tenants claimed to be on the organization’s Web site are up-to-date or actually on the campus. In fact, the City of Knowledge is not mentioned in the country’s Strategic Plan or by industry and banking leaders although officials said this redevelopment was the most significant things to happen in Panama since the invention of the canal. Efforts to reach American universities and nongovernmental organizations, such as Florida State University, the University of Virginia and the U.S. Peace Corps, who have signed collaborative educational exchange agreements with the City of Knowledge, also give little insight. But perhaps, this unwillingness to be forthcoming is merely the Panamanian way. More telling, though, are the classified dispatches of Panamanian politics written by the previous U.S. ambassador, which were embarrassingly revealed on the secret-spilling WikiLeaks, depicting a country that places its best foot forward for international public consumption while hiding a multimillion dollar scheme of drug smuggling, human trafficking, corruption, and shady political figures involved in almost every facet of the economy. I. INTRODUCTION The City of Knowledge’s success can be attributed to three economic development approaches: cluster theory, new growth theory, and creative class theory. For the purpose of the comparison with a similar American entity, a discussion on the Base Realignment and Closure Commission history, process, and examples are mentioned, though, they do not particularly relate to the City of Knowledge’s direct accomplishments. Clusters are geographic concentrations of interconnected companies and institutions in a particular field. Clusters encompass an array of linked industries and other entities important to competition. They include, for example, suppliers of specialized inputs such as components, machinery, and services, and providers of specialized infrastructure. Clusters also often extend downstream to channels and customers and laterally to manufacturers of complementary products and to companies in industries related by skills, technologies, or common inputs. Finally, many clusters include governmental and other institutions—such as universities, standards-setting agencies, think tanks, vocational training providers, and trade associations— that provide specialized training, education, information, research, and technical support. (Porter, 1998) New Growth Theory emphasizes economic growth from within the community coming from the increasing returns associated with new knowledge. Spillovers occur because knowledge is non-rival and not completely excludable so that more people benefit than the original inventor. In the aggregate, these increasing returns drive the growth. (Romer, 1986) Creative Class Theory helps explain how globalization and technology advances have allowed the most talented and educated people “whose main economic function is to create new ideas, new technology and new creative content” to forgo moving where companies are located. Instead, this group of scientists, engineers, writers, poets, graphic designers, architects, and performers prefer to find other equally talented people to congregate and collaborate with. (Florida, 2002) Economic development is fundamentally about enhancing the factors of productive capacity – land, labor, capital, and technology – of a national, state or local economy. By using its resources and powers to reduce the risks and costs which could prohibit investment, the public sector often has been responsible for setting the stage for employment-generating investment by the private sector. (U.S. Department of Commerce –Economic Development Administration, 2002) Regime Theory relates to the informal yet relatively stable group with access to institutional resources, and which has a significant impact on local policy and administration. (Stone, 1989) Growth Machine Theory refers to individuals or institutions directly benefit from economic development activity. (Cox & Mair, 1989; Logan & Molotch, 1988) Base Closure Law is the provisions of Title II of the Defense Authorization Amendments and Base Closure and Realignment Act (Pub. L. 100-526, 102 Stat.2623, 10 U.S.C. S 2687 note), or the Defense Base Closure and Realignment Act of 1990. (Pub. L. 100-526, Part A of Title XXIX of 104 Stat. 1808, 10 U.S.C. S 2687 note) “BRAC" is an acronym which stands for base realignment and closure. It is the process the Defense Department has used to reorganize its installation infrastructure. The process aims to more efficiently and effectively support its forces, increase operational readiness and improve business practices. (Defense Department, 2005) Redevelopment authority is the entity, including state or local government, recognized by the Secretary of Defense as the entity responsible for developing the redevelopment plan with respect to the installation or for directing the implementation of such plan. (Defense Department, 2005) Redevelopment plan is the term used to when an installation will close or be realigned that (A) is agreed to by the local redevelopment authority with respect to the installation; and (B) provides for the reuse or redevelopment of the real property and personal property of the installation that is available for such reuse and redevelopment as a result of the closure or realignment of the installation. (Defense Department, 2005) For the context of this paper, it is important to note the U.S military budget because it is the reason for studying Panama’s success with the “City of Knowledge.” While much of the media reporting on the 2013 Defense Department cuts numbering about nearly $500 billion over a decade focuses on troop reductions and putting off equipment purchases, Defense Secretary Leon Panetta in January alluded to other measures to save money. The following month, defense officials indicated that it would request two new rounds of base closures in 2013 and 2015. (Defense Budget Priorities and Choices, January 2012) Still, it remains dominating. Just months after President Obama delivered his 2012 State of the Union address, the U.S. Conference of Mayors assembled a task force in April to deal with one major aspect of Obama's policy -- the eventual drawdown on the wars, and, subsequent, cut of U.S. troops. Last month, Phoenix Mayor Greg Stanton, the task force chair, said in a press release that he will "work hard with mayors across the country to ensure that if cuts to the Defense budget are made, they are done so in a thoughtful manner that protects jobs and our nation's security." While much of the media reporting on the 2013 Defense Department cuts numbering about nearly $500 billion over a decade focuses on troop reductions and putting off equipment purchases, Defense Secretary Leon Panetta in January alluded to other measures to save money. The following month, defense officials indicated that it would request two new rounds of base closures in 2013 and 2015. (Defense Budget Priorities and Choices, January 2012) “Make no mistake: the savings that we are proposing will impact on all 50 states and many districts, congressional districts, across America,” Panetta said in a Pentagon briefing. “This will be a test, a test of whether reducing the deficit is about talk or about action.” An example of how BRAC previously impacted communities nationwide is below. Galena FOL Eielson AFB Elmendorf AFB BRAC 2005 Recommendations Kulis AGS Grand Forks AFB McChord AFB Umatilla CD Selfridge Army Activity Mt. Home AFB Gen. Mitchell ARS Great Lakes NS Rock Is. Arsenal Pittsburgh IAP AGS Newport CD Crane NSA Ft. Riley DFAS Army Res. Pers. Ctr. Ft. Knox Ft. Lee Kansas AAP Ft. Monroe Ft. Bragg/Pope AFB Ft. Sill Little Rock AFB Deseret CD Concord NWS Onizuka AFS Riverbank AAP China Lake NAWS Barstow MCLB Ventura City NB San Diego NMC DFAS Denver Ft. Carson Cannon AFB Sheppard AFB Red River AD Lone Star AAP Maxwell AFB Mississippi AAP Ft. Bliss Broadway Complex Athens NSCS Ft. Benning Eglin AFB Pensacola NAS Pascagoula NS Ingleside NS New Orleans NSA Corpus Christi NAS Orange NRC SYMBOL KEY Base Closure Realignment Growth Brunswick NAS Niagara Falls IAP AGS W.K. Kellogg AGS Otis ANGB Willow Grove NAS Brooks CB Lackland AFB Ft. Sam Houston Ft. Monmouth Aberdeen PG Ft. Meade Nat’l Geospace-IAA Bethesda NNMC Walter Reed AMC NCR Leased Space NDW Ft. Belvoir Quantico MCLB Atlanta NAS Ft. McPherson Ft. Gillen *Installation names in green font indicates OEA community contact Source: U.S. Department of Defense Office of Economic Adjustment 10/05 Comparing BRAC Rounds (TY $B) Major Base Closures Major Base Realignments Minor Closures and Realignments Costs1 ($B) Annual Recurring Savings 2 ($B) BRAC 88 16 4 23 2.7 0.9 BRAC 91 26 17 32 5.2 2.0 BRAC 93 28 12 123 7.6 2.6 BRAC 95 27 22 57 6.5 1.7 Total 97 55 235 22.0 7.3 3 BRAC 05 25 26 757 22.8 4.4 (Commission Rec’s) Note 1: As of the FY 2006 President’s Budget (February 2005) through FY 2001. Note 2: Annual recurring savings (ARS) begin in the year following each round’s 6-year implementation period: FY96 for BRAC 88; FY98 for BRAC 91; FY00 for BRAC 93; and FY02 for BRAC 95. These numbers reflect the ARS for each round starting in 2002 and are expressed in FY 05 dollars. Note 3: Does not add due to rounding. Source: Presentation by Mr. Philip W. Grone, Deputy Under Secretary of Defense (Installations and Environment), for the Economic Adjustment Committee on October 17, 2005. Panama’s population of 3.5 million people has experienced a 10 percent growth in GDP, up to $30.6 billion, in 2011, making it the fastest growing country in Central America, although, not everyone has benefited since 30 percent of the population lives in poverty, though it was reduced by 10 percent since 2006, and unemployment down to 3 percent. In 1990, the country disbanded its military, rather, establishing a national police force, at a cost of less than 1 percent of GDP. Instead, Panama's dollar-based economy rests primarily on operating the Panama Canal, logistics, banking, the Colon Free Zone, insurance, container ports, flagship registry, and tourism. The canal’s expansion is expected to be completed by 2014 at a cost of $5.3 billion, and will double the canal's capacity. (CIA Factbook) However, the good times may be coming to a halt. During the first quarter of 2012, the country’s foreign direct investment fell by 15 percent, according to the country’s Comptroller office. (La Prensa, 2012) Further, Japanese-based investment bank Nomura Securities sounded the alarm in June noting that while Panama’s economy grew by nearly 10 percent during the first quarter of 2012, leaders are showing little prudence in public expenditures, and off-books accountings mask the deteriorating fiscal accounts. Nomura has recommended an “exit strategy.” “We recommend zero exposure to Panamanian sovereign bonds. While this positioning might be relatively premature, we prefer to recommend it now in expectation of a sharp rise in fiscal spending for electoral reasons next year,” said analyst Boris Segura in a research note on Panama published in June. “For those that are currently involved in this credit, we think it may be opportune to begin executing an exit strategy.” (Segura, 2012) In January 2010, Panamanian President Ricardo Martinelli ushered in a new era bent on turning the small Latin American country into an international financial player. With the ongoing expansion of the Panama Canal, Martinelli set the sights for the country's trajectory even higher when he unveiled a 223-page strategic plan that outlined the goals of his administration for the next five years to achieve economic growth, poverty reduction, and ensure a better wealth distribution. The plan was “the first time that an administration, at the beginning of its term, presents a set of documents which will constitute its roadmap, a guide for the performance and execution of its economic, social, financial, and investment actions.” Even, the World Economic Forum was echoing the new tide, consistently listing Panama in the top-10 spots for banking, foreign direct investment, and port infrastructure in its 2011 Global Competitiveness Report. Long gone were the days of military Dictator Manuel Noriega and the ugly images of a country with little history and no apparent destiny. Even, U.S. officials were quick to acknowledge the impressive track record. Then-U.S. Ambassador Barbara Stephenson told members of the Florida Chamber of Commerce in August 2009 that Panama’s economy was taking a contrarian approach. “In the middle of a worldwide financial crisis, Panama has managed to show positive economic growth, and projections are for growth of two-three percent next year,” she said. “Panama is weathering this storm because it adopted good macro-economic policies over the last 10 years, and successive governments have taken steps to keep the country’s fiscal house in order.” (Stephenson, 2009) However, to members of the American Chamber of Commerce in Panama, she took a more lecturing tone two months later when she told business and industry leaders that the judicial system needed significant improvement for the Latin American country to improve its competitiveness rankings. “Panama’s ability to continue to attract and retain foreign direct investment would be bolstered by having an independent, impartial and efficient judicial system. In the Embassy, we will continue to be advocates for a strong judiciary, for adherence to the rule of law, and we hope you will as well.” (Stephenson, 2009) In classified cables to her bosses at the U.S. State Department, Stephenson was more candid, painting a picture of a corrupt government and its chief executive bent on dismantling some of Panama’s most powerful families, the Mottas and the Waked, a notion that was widely reported later. (Jackson, 2012) In even earlier dispatches intended for American officials only, Stephenson went so far as to call out Martinelli by name. "His strong personality, his lack of commitment to the rule of law, his exaggerated presidentialism and its popularity can be damaging to democratic institutions in Panama," she said in dispatches after he was elected. (WikiLeaks, 2011) In surprising chilling detail, Stephenson said the tax free zones and many of the expansion projects in Panama, namely the $80 billion effort at Tocumen International Airport and Panama Pacifico, a $10 billion redevelopment of former Howard U.S. Air Force Base, were alleged fronts for other notorious acts, such as drug smuggling, money laundering, human trafficking, highway armed robberies of tourists carrying large amounts of cash, and tax evasion for drug cartels. Panama's geographical advantages and open business climate have spurred Tocumen's growth. However, those same advantages have also facilitated a culture of corruption which has accompanied Tocumen's physical and commercial development. Money laundering, alien smuggling, and narcotics trafficking are proliferating. (WikiLeaks, 2011) She even named the sitting tourism minister as being involved in drug trafficking, and Martinelli’s own cousin, Ramon Martinelli, as part of a four-man operation that moved $30 million per month through the Tocumen airport. Stephenson’s documents became an open secret once they were posted on WikiLeaks. She has since been appointed deputy chief of mission in London. Martinelli is said to have visited the United States several times, but his first invitation to the White House came just last year before the Free Trade Agreement was signed. The ambassador is not alone in the concern of the sitting administration. In a research note on Panama, Boris Segura, the analyst from Nomura Securities, said that it would be very likely that Martinelli might be able to seek a second term in 2014, dismissing the law that does not allow consecutive reelection by stacking the sitting judiciary with his influence. These new magistrates would very likely reinterpret the Constitution in Martinelli’s favor. “If President Martinelli indeed runs for re-election in 2014, we think that Panama’s political environment will deteriorate fairly quickly,” Segura wrote. (Norma Securities, 2012) Twelve years after the United States handed over all military bases in Panama, few can recall a time when the Latin American country was a laboratory for testing on nerve agents and depleted uranium. Now, the former site of Fort Clayton is home to the 296-acre technology cluster known as the "City of Knowledge," which houses the world-class ecological facility Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, along with family residences, business office space and educational symposiums. While, many communities in the United States have seen similar relative successes, few have been able to do it outside the context of a strong national economy and the ultimate safety net provided by the federal government. (City of Knowledge) The success of the City of Knowledge has led to more success. Last March, officials broke ground on a ground is to be broken on a $20-million science and technology innovation park near Panama City; construction of a $5-million laboratory for the country’s research animals is planned for this spring; the government is funding about 100 Panamanians to undertake doctoral studies at universities abroad, with incentives to return to Panama for research careers; and the first complete in-country PhD research program — in biotechnology — has just begun at the Institute of Scientific Advances and High-Technology Services. Observers say that the country’s efforts at a scientific renaissance could even serve as a model for other nations seeking new life after conflicts. (Dalton, 2011) The focus of this report is how communities can best manage the impact in terms of the jobs losses, assets abandoned, and the opportunities that present themselves for private sector activity when the federal government vacates the area. Understanding base closures is important because it shifts the government's economic stimulus to the private sector, turning into a "complex nexus" of public-private negotiations and entities and the different means of calculating value: government's job creation versus the private sector's return on investment. (Sorenson, 2007) The City of Knowledge, as a business incubator, offers an opportunity to study the impact of this adverse loss, overcoming the limited links to established science networks, such as research institutions, private companies, and nongovernment organizations, and how three subsequent economic development approaches: cluster theory, new growth theory, and creative class theory, offer the best chance at turning matters around. With the impending slash of U.S. military spending, the topic couldn't be timelier. II. Information and Data Collection Approach The data collection will take the form of Internet searches, academic journal reviews, and interviews conducted in Panama of City of Knowledge officials. Table 1. Databases: Name, URL Location and Information used to Search Database’s Name URL CIA World Factbook https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/pm.html U.S. Defense Department Base Realignment and Closure http://www.defense.gov/brac/ Fitzsimmons Life Science District http://www.fitzscience.com/media/docs/State%20of%20Industry/Impact_Summary_2008_Final_Rev12909.pdf U.S. Defense Department Office of Economic Adjustment http://www.oea.gov/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=51&Itemid=46 Federal Facilities Restoration and Reuse Office http://www.epa.gov/fedfac/ffrro_library.htm#brac U.S. Conference of Mayors http://www.usmayors.org/pressreleases/uploads/2012/0411-release-defensetf.pdf Information Table 2. Keywords/Phrases Used for the Search Keywords Base Realignment and Closure Commission Fitzsimmons Life Science District Cluster Theory Creative Class Theory New Growth Theory Foreign base closures Panama The following questions were initially e-mailed to four City of Knowledge officials, including Jorge Arosemena, Manuel Lorenzo, Laru Linares, and Irene Perurena. (Source for questions: Northeast Indiana Innovation Center) 1. How are you funded? What’s the annual budget? 2. How does your organization differ from small business development organizations? 3. What services do you provide that give companies comparative advantages? 4. How does COK help start-ups get funding? 5. How many businesses are presently at COK? 6. How much space is available for businesses? 7. What are the benefits of being a business in the COK? 8. Does the COK work with existing businesses? 9. Does the rental price include utilities? 10. With funding from multiple sources, do businesses in the COK compete unfairly with local landlords? 11. What if the company isn’t in one of the focused industries? 12. Why is the COK worthy of government subsidies? 13. How does your organization differ from research parks? Or does it? 14. Is business incubation an industry? 15. What is entrepreneurship education? 16. Can a client stay at the City of Knowledge as long as they pay for rent? 17. Aren't you just taking existing companies from other parts of the community and moving them into your facility at 'below' market rates? 18. Does the COK contribute to local and regional economies? 19. Do business incubators differ from business accelerators? 20. Does a client company give up any equity to enter the COK? Are there other technology incubators in the region? 21. What is the price per square foot for office space? Under what circumstances do you terminate the office lease? City of Knowledge in Panama City. III. CASE STUDY In 2004, former President Martin Torrijos Espino ushered in a new direction for Panama and named Julio Escobar Villarrue, a computer scientist trained at MIT, as science minister. During his five-year term, Escobar offered $15 million in scholarships and grants that provided funding for several hundred graduate students to study abroad and established a system that rewards well-published researchers with stipends worth up to$2,000 per month. That included calling on old friends who had since departed Panama. (Dalton, 2011) In 2010, Carmenza Spadafora Mejía and colleagues won a $1 million grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to develop a full-body microwave scanner to cure malaria by killing the parasite that invades red blood cells. She had returned to Panama in 2008 after earning her doctorate in Spain. Stories like Spadafora’s are not exception because the country is seeking to create an “international science hub,” according to Ruben Berrocal Timmons, Panama’s science director, who says the country intends to increase investments in science and technology from less than .2 percent of GDP during the mid-2000s to .6 percent by 2014. (Dalton, 2011) Intuitively, when Torrijos hired Escobar who then contacted Spadafora, the emergence of the Creative Class Theory was at work. It explains how globalization and technology advances have allowed the most talented and educated people “whose main economic function is to create new ideas, new technology and new creative content” to forgo moving where companies are located. Instead, this group of scientists, engineers, writers, poets, graphic designers, architects, and performers prefer to find other equally talented people to congregate and collaborate with. (Florida, 2002) With first-class amenities, as Bremer discovered, life in the City of Knowledge doesn’t seem to resemble any third-world country. Along with tax and immigration benefits, facilities include a convention center, training and business center, sports and recreational facilities, executive office centers, videoconference rooms, digital classrooms, residential villas, schools, daycare centers, restaurants, bakeries, medical centers, university research centers, access to the Panama Canal Basin for advanced tropical ecosystem research, Internet and guaranteed electricity. (City of Knowledge) The reinvention of Fort Clayton into a science sector demonstrates the geographic concentrations of interconnected companies and institutions in a particular field. Clusters encompass an array of linked industries and other entities important to competition, and often extend downstream to channels and customers and laterally to manufacturers of complementary products and to companies in industries related by skills, technologies, or common inputs. Finally, many clusters include governmental and other institutions—such as universities, standards-setting agencies, think tanks, vocational training providers, and trade associations— that provide specialized training, education, information, research, and technical support. (Porter, 1998) The tentacles of biomedicine have reached other places such as Hospital Santo Tomás, where researchers are working with pharmaceutical companies on clinical trials. And, the added benefit of the Panama Canal’s expansion will come from the excavation for the new locks to enlarge it – fossils of animals will help understand migration between North and South America. (Dalton, 2011) In 1995, Fitzsimons Army Medical Center in Aurora, Colorado, was selected for closure, ultimately, shuddered its doors as a federal installation in 1999. Since, the redevelopment at Fitzsimons has turned it into a 577-acre Life Sciences City with an investment of $4.3 billion that focused on patient care, teaching, basic-science research, and biotechnology research and development (R&D) will thrive by being collocated in a scientific-entrepreneurial community. It resulted from a partnership between the University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center, the University of Colorado Hospital, the city of Aurora, the Children’s Hospital, and the Fitzsimons Redevelopment Authority. Total planned construction is projected at 15 million square feet, and total employment at completion of redevelopment in 2020 is projected at 32,000. Approximately half of the redevelopment program and 19,000 jobs will be at the site by 2010. (Economic Transition of BRAC Sites: Major Base Closure and Realignments 1998-2005, 2006) Federal officials contend that the redevelopment of base property is widely viewed as a key component of economic recovery for communities experiencing economic dislocation due to jobs lost from a base closure. The closure of a base makes buildings and land available for use that can generate new economic activity in the local community. For instance, the $1.5 billion Fitzsimons Life Science District and Anschutz Medical Campus in Aurora, Co. combined for 578 acres of health care, education and research after a BRAC closure in 1999. Targeted for redevelopment into a healthcare and science research center, it was renamed in recognition of the $91 million donated by the Anschutz Foundation, a charity started by the parents of billionaire oil, rail and sport investor Philip Anschutz. The campus employs about 15,000 people and generates more than $3 billion in economic activity through The Children’s Hospital, the University of Colorado Hospital system, VA Medical Center, and health sciences education and research facilities. By 2030, officials say it will employ a staggering 44,000 jobs and generate nearly $7 billion a year. (Leslie & Lewis, 2009) “Fitzsimons’ closure has probably been the best thing that has ever happened to the City of Aurora,” said Jill Sikora-Farnham, acting executive director of the Fitzsimons Redevelopment Authority. “We’ve more than replaced the military employment and that’s just going to continue to increase.” (Office of Economic Adjustment. 2005) Also, the Defense Department said it expected to save nearly $29 billion through 2003 and $7 million every year thereafter with the closures. (GAO, 2005) While, many communities in the United States have seen similar relative successes, few have been able to do it outside the context of a strong national economy and the ultimate safety net provided by the federal government. For instance, Fitzsimons’ four phases received nearly $14 million from the state’s Department of Transportation and $400 million in the American Recovery & Reinvestment Act funding, and the donation from the Anschutz family. In fact, through mid-1999, federal agencies had provided nearly $2 billion for planning, infrastructure development, labor force assistance, and the development of civilian airports and other facilities important for job creation. (Baxter & Frieden, 2000 & GAO, 2005) Further, the same Government Accountability Office report that said the Defense Department could save billions had its doubts, and, more pointedly, indicated that through 2003, the Defense Department had spent $8.3 billion on environmental cleanup and expected to shell out another $3.6 billion more to complete the job. (GAO, 2005) Fitzsimons Life Science District and Anschutz Medical Campus in Aurora, Colorado, a suburb of Denver. IV. RESULTS AND RESULTS IMPACTED SIMILARITIES CRITERIA CITY OF KNOWLEDGE Result from base closure Redevelopment Science cluster Biomedicine, technology Academic focused Panamanian/American universities Expansion possibilities Commercial enterprise Limited 185 entities FITZSIMONS Redevelopment Biomedicine, Technology University of Colorado, Children’s Hospital, Veterans Affairs Hospital Open About 50 The similarities results are important because, all things being equal, it gives the case studies something measurable to examine despite the obvious difference in the scale of the two entities. DIFFERENCES CRITERIA Capital investment Languages Economy of scale Tax incentives Knowledge base CITY OF KNOWLEDGE Unknown Spanish/English/German Unknown Unknown Science cluster FITZSIMONS $4.3 billion English 44,000 jobs; $7 billion Unknown Science cluster This differences result is important because information asymmetry is prevalent in Panama, and the conditions under which one does business there is questionable. There is definitely a case of caveat emptor. For the purpose of this research paper, just what can we learn from the City of Knowledge is unknown. V. SUMMARY Even in the United States, among publicly-traded pharmaceutical companies, geography explains how firms located in clusters exhibit superior firm value, with evidence that supports the notion that geographic sources of competitive advantage contribute positively to firm value. (Boasson et al, 2005) The positive correlation of agglomeration economies allows for minimal transaction costs between suppliers and buyers within localized networks (Huggins 2000). The technological spillover from major research universities located in the cluster creates higher local economies that might not otherwise be there. (Acs, Anselin, & Varga, 2000). This geographic concentration also affords the economic growth from within the community coming from the increasing returns associated with new knowledge, known as New Growth Theory. Spillovers occur because knowledge is non-rival and not completely excludable so that more people benefit than the original inventor. In the aggregate, these increasing returns drive the growth. (Romer, 1986) Globalization opens this possibility with the emergence of technology-intensive entrepreneurial initiatives in countries that are developing a science base. The challenge though is to connect to the international science networks that require a combination of indigenous (domestic) scientific competencies and a pool of skilled human resources with transnational linkages with a reliance on the entrepreneurial firms capacity to plug into the “knowledge value chains.” (Fontes, 2007) For Latin American and Caribbean countries, this is no less a struggle where misguided public policies have resulted in development gaps not only with major Western Powers, but with other countries, such as South Korea and Taiwan, where were at similar development levels 20 years ago. Without the cluster, not only were the major players not strong, but the links between them tending to be weak as well. The system of innovation may operate more efficiently so it identifies the participant social actors, mapping the knowledge flows among them, the bottlenecks and suggestions for remedial actions. (Velho, 2005) These transnational linkages that create the linkages are most critical for companies still in their formative years. In some measure, the early success of the City of Knowledge stems from solving the problem of transforming knowledge into commercialized products, particularly, in biotechnology. The span of knowledge is necessary and depends on the regional setting and those in these incubator-like settings have a more secure future, and the firms collocated in these incubators have an advantage of extracting commercial businesses from adjacent labs, amongst which many are gearing up for entrance into the North American markets. Finally, "boundarycrossing" institutions with established social capital serve as knowledge management intermediaries, “without which clusters would probably not exist in less accomplished regional settings.” (Cooke, Kaufmann, Levin, & Wilson, 2006) Nowhere in Martinelli’s plan is there a mention of the “City of Knowledge,” the business incubator located at the former site of Fort Clayton. In fact, it isn’t even a blip on the economic development radar, even, with its tax incentives and highly visible tenants, such as the United Nations and the United States Peace Corps. Nearly two weeks before arriving in Panama, City of Knowledge officials were sent a list of questions on how the incubator ran. These questions were adopted from frequently asked questions of the Northeast Indiana Innovation Park, all of which are listed on its Web site. They were hardly the stumping questions asked by a seasoned investigative journalist. Yet, City of Knowledge officials declined to answer them, and refused to meet with a group of students from the University of Southern Mississippi. In fact, even, in a follow-up e-mail, City of Knowledge officials was not returned. So what can be learned from the City of Knowledge? In a nutshell, it is too early to tell. Nearly eight years ago, Eric Johnson, an expat who runs the left-leaning blog Panama News, covered an event where Jorge Arosemena, the head of the City of Knowledge, listed off the goals of the fledgling incubator. “Attracting people from outside was always key,” Arosemena said in the July 2003 report. “Just within Panama we can’t get all the people we need to become what we want to be.” (Jackson, 2003) Arosemena counted a dozen American leading universities among the academic program tenants, including Florida Atlantic University, Florida State, Southern Methodist University, Cornell University, the University of California at Davis, Texas A&M, Iowa State, McGill, Universidad San Martin, St. Clair College, Williams College and Tulane. According to the report, Arosemena said Panama’s location at the intersection of five major undersea fiber optic cables may one day be of more economic relevance than the Panama Canal, and at the moment it makes the City of Knowledge one of the world’s best-connected spots from the telecommunications point of view. That was said to be a major reason for luring phone company, Telecarrier, and 27 other businesses. The City of Knowledge derived income from serving as the landlord for international organizations, such as the U.N. regional office. Arosemena says that his goal is for 90 businesses in the incubator within six years, with the understanding that some of them will fail and the bottom line being some 700 jobs, the report said. But, not all that shines is gold. Officials from the City of Knowledge declined repeated requests for interviews, and it remains unclear whether the tenants claimed to be on the organization’s Web site are up-to-date or actually on the campus. In fact, the City of Knowledge is not mentioned in the country’s Strategic Plan or by industry and banking leaders. Efforts to reach American universities, such as Florida State University and University of Virginia, who have signed collaborative educational exchange agreements with the City of Knowledge, also give little insight. More telling, though, are the classified dispatches of Panamanian politics written by the previous U.S. ambassador, which were embarrassingly revealed on WikiLeaks, depicting a country that places its best foot forward for international public consumption while hiding a multimillion dollar scheme of drug smuggling, human trafficking, and corruption in almost every facet of its economy. Whether any of these lofty goals has occurred is unclear, and Arosemena declined to be interviewed to ascertain such answers. More interestingly, the same developer who is working the Panama Pacifico project, which is the redevelopment of another former American military base, was brought in last year to the City of Knowledge to see if there were business opportunities available. REFERENCES CITED Acs, Z., Audretsch, D., Feldman, M. “Real effects of academic research.” American Economic Review. Vol. 81. 1992. Baxter, C. & Frieden, B. “From Barracks to Business: The M.I.T. Report on Base Redevelopment.” Massachusetts Institute of Technology. 2000. Boasson, V., Boasson, E., MacPherson, M., Han Shin, H. “Firm Value and Geographic Competitive Advantage: Evidence from the U.S. Pharmaceutical Industry.” The Journal of Business. Vol. 78, No. 6. 2005. City of Knowledge. http://www.ciudaddelsaber.org. (nd) Cooke, P., Kaufmann, D., Levin, C., & Wilson, R. “The Biosciences Knowledge Value Chain and Comparative Incubation Models.” The Journal of Technology Transfer. Vol. 31. 2006. Cox, K. & Mair, A. “Levels of Abstraction in Locality Studies.” Antipode. 21:2. 1989. Dalton, R. “Panama’s Big Ambition.” Nature. Vol. 469. 2011. Dewey-Ives, D. “Transforming the Suburban Landscape: One Community’s Attempt to Adapt to a Knowledge-based Economy.” Planning Practice & Research. Vol. 26, No. 1. 2011. “Defense Budget and Priorities.” Defense Department. 2012. “Economic Transition of BRAC sites: Major Base Closures and Realignment 1988-2005.” Defense Department. Office of Economic Adjustment. Washington DC. 2006. Florida, R. The Rise of the Creative Class. Basic Books. New York. 2002. Fontes, M. “Technological Entrepreneurship and Capability Building in Biotechnology.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management. Vol. 19, No. 3. 2007. Herb, J. “House Says No to More Base Closures.” The Hill. 2012. Huggins, R. “The success and failure of policy-implanted inter-firm network initiatives: Motivations, processes and structure.” Entrepreneurship and Regional Development. Vol. 12. 2000. Jackson, E. Personal Interview by E-mail. 2012. Jackson, E. “City of Knowledge Goals, Successes Outlined.” The Panama News. 2003. La Prensa. “Foreign Investment Fell 15.3 Percent.” 2012. Leslie, M. & Lewis, P. “Economic Engine Evolving Plans for Fitzsimons Will Transform Underused Land into a World-class Venue.” Colorado Construction. 2009. Logan, J. & Molotch, H. Urban Fortunes: The Political Economy of Place. University of California Press. Berkley. 1988. “Military Base Closures: Updated Status of Prior Base Realignments and Closures.” U.S.Government Accountability Office. 2005. Paloyo, A., Vance, C., Vorell, M. “The Regional Economic Effects of Military Base Realignments and Closures in Germany.” Defence and Peace Economics. Vol. 21. 2010. Panetta, L. “Statement on Major Budget Decisions.” Speech. 2012. Porter, M.E. On Competition. Harvard Business School. 1998. “Renaissance: New Jobs, Uses of Space and Resources.” Defense Department. Office of Economic Adjustment. 2005. Riddle, J. “Teacher, Adventurer, Citizen of the World: Choosing the Road Less Traveled.” Internet@School. 2011. Romer, P. “Increasing Returns and Long Run Growth,” Journal of Political Economy. Vol. 94. 1986. Segura, B. “Panama: Selling the Crown Jewels.” Nomura Securities. 2012. Sorenson, D. Military Base Closure: A Reference Handbook. Praeger Security International. Connecticut. 2007. Stephenson, B. “Ambassador Stephenson's Speech at the 2009 Annual Chamber Community Conference in Plantation, Florida.” Speech. 2009. Stephenson, B. “Ambassador Stephenson's Remarks at the American Chamber of Commerce 30th Anniversary Celebration.” Speech. 2009. Stone, C. Regime Politics. University Press of Kansas. 1989. Teschler, L. “We Don’t Know How to Recreate Silicon Valley.” Machine Design. 2008. The World Bank. Washington DC. http://data.worldbank.org. (nd) WikiLeaks. http://wikileaks.org. 2011. Vehlo, L. “S&T institutions in Latin America and the Caribbean: An Overview.” Science and Public Policy. Vol. 32, No. 2. 2005. Woodard, C. “In a swap of sword for pen, Panama wants U.S. base to be knowledge city.” Christian Science Monitor. 1997. World Factbook. U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. Washington DC. (nd)